Employer attractiveness in the Chemical Industry: Investigating the impact of product novelty, product relevance, and work meaningfulness

While research on employer attractiveness has traditionally focused on external employer branding, less is known about what attracts employees to stay. This study examines how product-related factors—specifically perceived novelty and societal relevance—relate to internal employer attractiveness, and whether these relationships are mediated by meaningful work. We develop and test a mediation model using two-wave survey data from 138 employees of a global chemical company. Results show that perceived product novelty has a significant positive relationship with employer attractiveness, partially mediated by meaningful work. Perceived product relevance, however, does not show a direct relationship, but an indirect one via meaningful work. These results highlight that perceived product characteristics – beyond traditional HR instruments – can contribute to how employees evaluate their employer. The study extends the internal employer branding literature by integrating product-driven perceptions and meaningfulness into the understanding of organizational attractiveness.

Keywords: Employer attractiveness, Product relevance, Product novelty, Product innovation, Meaningful work, Internal employer branding, Employee perception

Introduction

Customers will never love a company until the employees love it first. (Simon Sinek)

The literature on how to position organizations as attractive employers has been intensively developed during the last decades since Ambler and Barrow (1996) published a study focusing on employer branding, meaning the actions undertaken by an organization to develop employer knowledge (Theurer et al., 2018). The outcome of activities to enhance the employer brand is a “package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment and identified with the employing company” (Ambler and Barrow, 1996, p. 187).

Turban and Greening (1997) introduced the term employer attractiveness as the degree to which a respondent would personally seek an organization as an employer. Berthon et al. (2005) concluded that there was a high similarity between the employer brand and internal employer branding. They showed that employees are attracted to their employers based on the five dimensions: economic value (compensation and benefits, job security, and opportunities for promotion), development value (recognition, self-worth, confidence, and future employment), interest value (exciting work environment, e.g., innovative products and services), social value (a fun-oriented and happy working environment, team atmosphere, etc.), and application value (opportunity to apply as well as teach others what was learned). Turban and Cable (2003) argue that applicants lack the experience of working in the target organization yet, and their perceptions might not provide complete and accurate information about the employment experience. This distinction between applicants and employees laid the foundation for later research, which began to explore employer attractiveness from the perspective of the workforce of an organization. From a signalling perspective (Spence, 2002; Lievens and Highhouse, 2003), organizations rely on observable cues to communicate their attractiveness, yet once employees are inside, such signals are complemented and reinterpreted through daily work experiences.

Over the following decades, the main focus of research remained on applicants rather than on the perception of those already working in an organization (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003; Lievens et al., 2007). More recent studies with employees have mostly highlighted HR related drivers such as work atmosphere, training and development, ethics and CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility), or compensation and benefits (e.g., Tanwar and Prasad, 2017; Maurya and Agarwal, 2018; Vnouckova et al., 2018). These findings underline that HR practices are crucial, but they leave open the question of whether other factors that differentiate organizations, such as organizational products themselves, influence how employees perceive their employer.

This omission is noteworthy because employees, like customers, are constantly exposed to their organization’s products and services. Branding research suggests that product attributes such as novelty and societal relevance are central to how stakeholders evaluate organizations (Aaker and Shansby, 1982; Aaker, 2004). Aaker (2004), in particular, emphasizes that corporate brands embody organizational values, innovation, and citizenship programs, and that these associations are vital for internal brand building. Extending this logic to the employee perspective suggests that product attributes may also shape employer attractiveness beyond traditional HR signals.

Against this background, we focus on two product dimensions that are theoretically grounded and directly relevant for employees’ evaluations: product novelty and product relevance. Product novelty reflects perceptions of innovation and vitality, signalling to employees that the organization is dynamic and future oriented. Product relevance reflects the perceived societal value of products, signalling a broader purpose and contribution to society. Both dimensions are well established in branding and innovation research (e.g., Aaker, 2004; Sommer et al., 2017), but they have not been systematically examined in relation to employer attractiveness among employees. Further, drawing on a signaling theory (Spence, 2002) and a sensemaking perspective (Weick, 1995), we argue that meaningful work, defined as work that is perceived as particularly significant and holding a positive meaning (Rosso et al., 2010), is an important mediating mechanism explaining the relationships between perceive product characteristics and employer attractiveness. Specifically, perceived product novelty and relevance would enable would enable people feel sense of pride and contribution enabling experiencing meaningfulness at work (Glavas & Lysova, 2025; Pratt & Ashforth, 2003).

By introducing perceived product novelty and relevance, our study makes three contributions. First, we extend the employer attractiveness literature by moving beyond HR-related factors and incorporating product based perceptions as additional factors (Berthon et al., 2005; Tanwar and Prasad, 2017; Maurya and Agarwal, 2018; Vnouckova et al., 2018; App and Buettgen, 2016; Uen et al., 2015). Second, we theorize that the effects of perceived product attributes are mediated by employees’ sense of meaningful work, thereby linking branding insights (Aaker, 2004) to organizational behavior research concerned with how meaningful work can be fostered in organizations (Lysova et al., 2019; Rosso et al., 2010). Third, we study a critical case in the chemical industry—a sector often described as a “dirty industry”— to show that perceived product innovation and societal contribution can strengthen the internal employer brand even under challenging external conditions (King and Lenox, 2000).

Taken together, this study addresses an important gap by integrating product-related perceptions into the understanding of employer attractiveness from the employee perspective. We argue that perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance, alongside meaningful work, provide a more complete picture of what makes an employer attractive to its workforce.

This article is structured as follows. In the next section, we develop our theoretical framework and hypotheses concerning the role of perceived product novelty, perceived product relevance, and meaningful work for employer attractiveness. We then describe our research design, data collection, and measures, followed by the presentation of results. Finally, we discuss theoretical and practical implications, outline limitations, and suggest directions for future research.

Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

Our theorizing and hypotheses are formulated at the individual level of analysis, i.e., they concern employees’ perception of product novelty and product relevance, and how these perceptions relate to employer attractiveness via meaningful work.

Employer attractiveness of an organization

Since Ambler and Barrow (1996) foundational exploratory study “The employer brand”, testing the application of brand management techniques to human resources (HR) with interviews with HR professionals, the topic of employer brand and employer attractiveness has constantly developed into a field of interest to researchers and practitioners. Employer brand is defined as “the package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment, and identified with the employing company” (Ambler and Barrow, 1996, p. 187). While Amber and Barrow had already in their work suggested a relationship between employees, word of mouth and successful recruiting of new employees, early research mostly focused on employer attractiveness as perceived by applicants and not by employees of an organization (Dassler et al., 2022; Lievens and Highhouse, 2003).

Following the research of Ambler and Barrow (1996), there have been numerous studies investigating the concept of attributes and outcomes of an attractive employer (e.g. Lievens and Highhouse, 2003; Backhaus and Tikoo, 2004; Berthon et al., 2005). Organizational attractiveness or employer attractiveness is regularly defined as the benefits applicants anticipate from working for a specific organization (Berthon et al., 2005).

Organizational attractiveness is also considered the power that encourages employees to stay, as well as the degree to which employees and applicants perceive the organization as a good place to work. It is posited that companies with strong employer brands can reduce the cost of employee acquisition, improve employee relations, and increase employee retention (Berthon et al., 2005). The values provided by an employer can be differentiated into social, development, application, safety, and economic values (Berthon et al., 2005). In exchange for the values provided by an organization, employees not only dedicate their working hours. Research indicates that different levels of those values also have positive outcomes like employee engagement and identification (Schlager et al., 2011), linking employer attractiveness to the literature around employee engagement and identification.

Over the past decades, the main focus of the research has been on employer attractiveness in the eyes of applicants (Dassler et al., 2022). The specific perspective of employees, however, differs significantly from the perspective of applicants. According to signalling theory (Spence, 2002), in contexts with asymmetric information, actors rely on observable signals to form judgments about otherwise unobservable qualities. Applied to organizations, employer branding activities serve as signals that shape outsiders’ perceptions (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003). For applicants, such signals are especially important because they lack direct experience with the organization. In contrast, employees gradually replace external signals with their own experiences. This raises the question of whether other signals—such as the nature of the organization’s products—continue to shape how employees perceive their employer once they are inside the firm.

Although employees have richer information than applicants, much of the organizational environment remains uncertain or ambiguous, for example with

respect to long-term strategy, future product pipeline, or market prospects. In such contexts of residual information asymmetry, product characteristics continue to function as organizational signals (Spence, 2002). Employees then actively interpret these signals through sensemaking processes (Weick, 1995), which shape their evaluation of meaningful work and, ultimately, employer attractiveness.

Perceived product novelty, perceived product relevance, and employer attractiveness

Products and services are an integral part of any organization, not only for customers but also for employees. Aaker (2004) emphasized that corporate brands derive their strength from organizational associations such as innovation, vitality, and societal contribution. These product-related associations are not limited to external stakeholders but can also be internalized by employees as part of their evaluation of the organization. From a signalling perspective (Spence, 2002), products serve as visible cues that communicate qualities of the organization. Innovative and socially impactful products may signal vitality, credibility, and purpose, thereby shaping how employees perceive their employer. Thus, products can be understood as organizational signals that provide input into employees’ evaluations of their employer. This reasoning is consistent with research that links symbolic attributes such as innovativeness and progressiveness to employer attractiveness (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003; Sommer et al., 2017) as well as studies connecting corporate social responsibility to employees’ organizational identification (Klimkiewicz and Oltra, 2017; Pratt and Ashforth, 2003).

Against this background, we focus on two product dimensions that are theoretically grounded and directly relevant for employees’ evaluations: perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance. Perceived product novelty signals organizational competence, adaptability, and forward momentum, attributes that employees interpret as indicators of long-term viability and professional pride (Spence, 2002; Aaker, 2004). Novel products demonstrate that the organization is dynamic and future-oriented, which enhances employees’ sense of belonging to a successful and innovative employer. Prior work confirms that symbolic attributes such as innovativeness and prestige positively influence organizational attractiveness (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003; Sommer et al., 2017). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Perceived product novelty positively relates to the internally perceived employer attractiveness.

Perceived product relevance captures the extent to which employees see their organization’s products as useful, valuable, and beneficial for society. Such perceptions provide employees with a sense that their daily work contributes to a greater purpose beyond economic outcomes. In signalling terms (Spence, 2002), relevant products communicate that the organization is committed to societal needs, which strengthens employees’ identification with the firm. This logic is consistent with prior CSR research showing that employees derive meaningful work when they perceive their employer as contributing to the common good (Aguinis and Glavas, 2019; Glavas and Lysova, 2025; Klimkiewicz and Oltra, 2017). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived product relevance positively relates to the internally perceived employer attractiveness.

Perceived product novelty, perceived product relevance and meaningful work

Meaningful work refers to “work experienced as particularly significant and holding more positive meaning for individuals” (Rosso et al., 2010, p. 95). Prior research emphasizes that meaningful work arises from alignment between individual motives and organizational contexts (Pratt and Ashforth, 2003; Lysova et al., 2019; Bailey et al., 2019). In this context, CSR is commonly defined as “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance” (Aguinis and Glavas, 2012, p. 933). CSR has also been shown to provide employees with opportunities to experience their work as contributing to a greater good, thereby functioning as an important contextual source of meaningful work (Aguinis and Glavas, 2019; Glavas and Lysova, 2025).

Extending this logic to product-related factors, we argue that perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance can both function as organizational signals that foster meaningful work. Novelty conveys vitality and innovativeness, which can generate employee pride and sense of contribution to a dynamic organization. Relevance, in contrast, parallels insights from CSR research by signalling that products serve societal needs, thereby strengthening employees’ experience of purpose and meaningfulness in their work. Based on these theoretical arguments, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: Perceived product novelty is positively related to meaningful work.

Hypothesis 4: Perceived product relevance is positively related to meaningful work.

Research consistently shows that meaningful work is a central component of positive organizational experiences. For example, employees who perceive their work as meaningful report higher engagement, stronger organizational identification, and greater commitment (Bailey et al., 2019; Allan et al., 2019). When employees believe that their work contributes to a greater purpose, they are more likely to develop positive attitude toward their employer and see the organization as a desirable place to stay. Prior research also indicates that meaningful work strengthens organizational identification and reduces turnover intentions, both of which are closely linked to perceptions of employer attractiveness (Allan et al., 2019; Lysova et al., 2019). Thus, meaningful work represents a key pathway. Based on this reasoning, we propose:

Hypothesis 5: Meaningful work is positively related to the perceived employer attractiveness.

From a signalling perspective (Spence, 2002), product characteristics provide observable cues of organizational qualities such as innovation, vitality, or societal contribution. However, signals alone are not sufficient to shape employer attractiveness. Employees actively interpret these signals through sensemaking processes (Weick, 1995), which shape their experience of meaningful work. In case of perceived product novelty, employees may interpret innovative products as evidence that their organization is dynamic, future oriented, and successful. This fosters pride and vitality in their work, which translates into stronger sense of meaningfulness. In turn, meaningful work makes the organization more attractive to employees, above and beyond the direct effect of perceived product novelty. We therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 6: The relationship between perceived product novelty and perceived employer attractiveness is mediated by meaningful work.

In case of perceived product relevance, employees may interpret socially valuable products as a signal that the organization contributes to societal needs and the common good. Such products create purpose at work, which strengthens employees’ sense of meaningfulness. It is through this experience of meaningful work, rather than a direct effect, that perceived product relevance enhances employer attractiveness. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 7: The relationship between perceived product relevance and perceived employer attractiveness is mediated by meaningful work.

Methods

Research setting

The empirical context of this study is a global chemical manufacturing company with more than 30,000 employees worldwide. It serves as an appropriate research setting for testing our hypotheses for several reasons. First, the company consists of different business divisions with products varying from very mature products to very innovative or new products. Second, the company’s products are solely sold to other manufacturing companies and not directly to end customers. Therefore, it is difficult to identify with the products, e.g., a certain chemical substance. A positive correlation with employer attractiveness likely has an even greater effect on consumer goods. Third, several recent product innovations can also be considered to serve the trend of sustainability by being “green” alternatives to the more traditional chemical products of the company. Accordingly, we expected to observe sufficient individual variance in our model.

Data collection and sample description setting

Procedure

The level of analysis in this study is the individual employee. To collect data, we reached out to the HR department of the company, who supported us by sending out the survey (see Table 1, Appendix) to 1,500 randomly selected employees from three globally operating business divisions. We collected the data in two waves during the period between April to October 2021. The first primary data (T1) was collected in June 2021, and the second data collection (T2) was conducted in September and October 2021, two months after the primary data collection. For both data collections, the same 1,500 employees were contacted via an online survey that was distributed through email, including the information that the data collection with the same questions will be ran twice. Surveys were administered in German and English, the two main working languages of the company. To ensure conceptual equivalence across languages, we followed a standard translation back translation procedure (Brislin, 1980). All survey items were first translated from English into German by a bilingual researcher, and then independently back translated into English by another bilingual researcher. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved in consultation with the research team to ensure accuracy and consistency of meaning.

Out of a total of 1,500 surveys sent out globally, we received usable responses from 246 employees (16.4% response rate) in summer 2021 and from 226 (15.1% response rate) in fall 2021. A total of 138 usable responses (9.2% response rate) were collected from the same respondents at both collection waves. For both data collections, we tested for nonresponse bias by comparing key attributes of respondents and non respondents.

Sample

Participants of the final sample (n = 138) were 138 working adults from across the globe. Of the participants who answered the items, 85 (62%) were men and 52 (38%) were women; with a mean age of 39.33 (Range = 21 – 52, SD 8.72). Regionally, 87 (63%) were based in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, including Germany, 34 (25%) were based in the Americas, and 17 (12%) were located in Asia. Participants were asked to voluntarily select their main area of work, with the majority indicating they work in production (37, 27%), 25 (18%) worked in administration and 10 (7%) worked in research, while the remaining indicated “other”. The majority of participants (79, 57%) had more than three years of work experience.

Measurement, construct validation and control variables

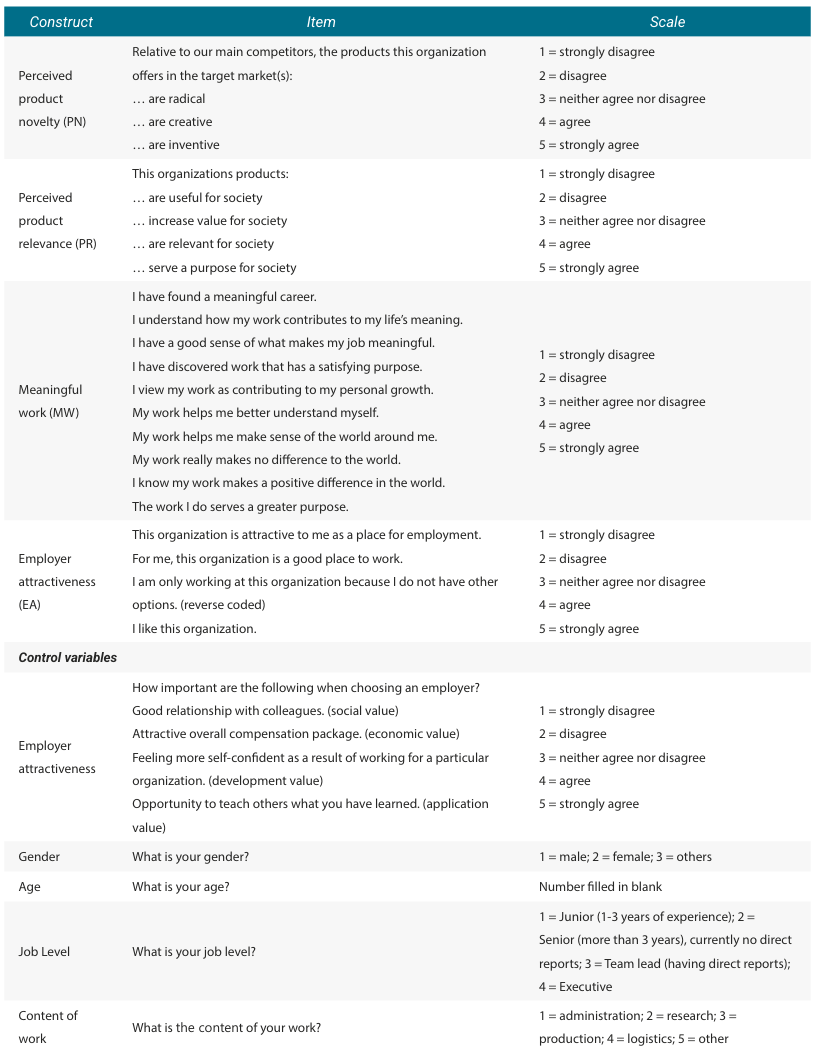

All variables were measured using five-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), and their order here follows the presentation in Tables 2 and 3 (see Appendix).

Employer attractiveness. The perception of employer attractiveness (T2) was measured with a four-item scale adapted from Highhouse et al. (2003), who introduced a framework to measure attraction to organizations along three dimensions: general attractiveness, intention to pursue and prestige. We adapted the five items from the general attractiveness dimension to the four items used in our research, e.g., ‘For me, this organization is a good place to work’. Reliability analysis indicates that the scale has good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Perceived product novelty. Perceived product novelty (T1) was measured using the three-item scale that Story et al. (2014) used to describe product innovation and novelty, e.g., ‘Relative to our main competitors, the products this organization offers in the target market(s) are radical’. Reliability analysis indicates the scale is internally consistent, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.71.

Perceived product relevance. Perceived product relevance (T1) was measured with the adapted scale of Im et al. (2015), by using four of the items that were used to measure relevance for customers. We replaced ‘customer’ with ‘society’, e.g. ‘This organization’s products are useful for society’. Reliability analysis indicates that the scale has good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Meaningful work. Meaningful work (T2) was measured using the ten-item scale of the Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI; Steger et al., 2012). The scale consists of three dimensions: positive meaning, e.g., ‘I have found a meaningful career’, meaning making through work, e.g., ‘I view my work as contributing to my personal growth’ and greater good motivations, ‘I know my work makes a positive difference in the world’. We used an aggregated score of meaningful work. Reliability analysis indicates the scale has good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91.

Control variables. We included factors that prior research identified as important for employer attractiveness (Berthon et al., 2005). Specifically, we measured social value, economic value, development value, application value. These items do not represent subdimensions of our dependent variable but capture alternative explanatory factors that could influence attractiveness perceptions. These controls allowed us to examine the unique contribution of product-related variables beyond established HR-related drivers. We controlled for age and gender since the work of Albinger and Freeman (2000) and Reis and Braga (2016) indicates that female and male applicants of different generations may assess organizational attractiveness factors differently. We included job level as a control variable because the relevance of prestige attributes like products may be more important the higher an employee ranks within an organization. Lastly, we controlled for the functional area of the job because functions may differ in the extent to which they are exposed to products.

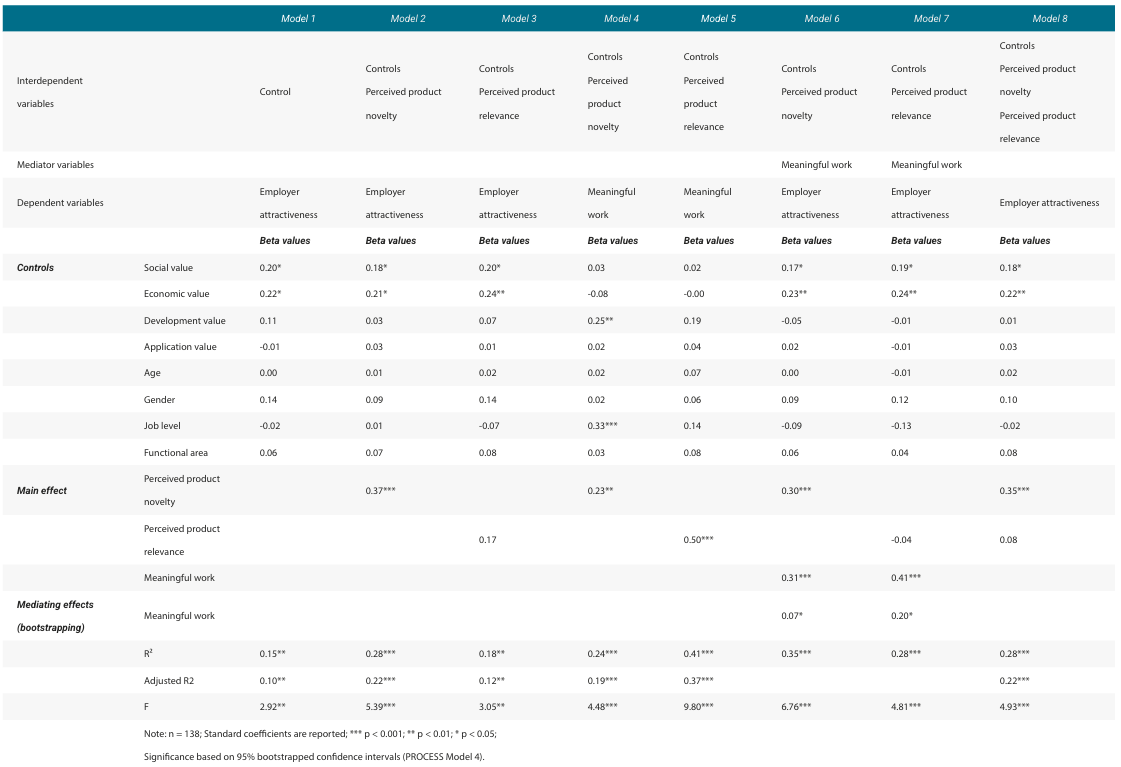

We used multiple ordinary least squares regressions to check for compliance with Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four requirements for mediation: (1) the independent variables significantly predict the dependent variable; (2) the independent variables significantly predict the mediating variable; (3) the mediating variable significantly predicts the dependent variable; and (4) when the mediating variable is introduced, the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable is significantly reduced, and the mediating variable significantly accounts for the variability in the dependent variable. Model 1 shows the effects of the control variables, while with Models 2 and 3, we test the first mediation requirement. Models 4 and 5 represent the second requirement of the mediation analysis, and Models 6 and 7 represent the third and fourth requirement. Finally, Model 8 included both, perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance simultaneously and tested for potential omitted-variable bias on employer attractiveness.

Analysis and Results

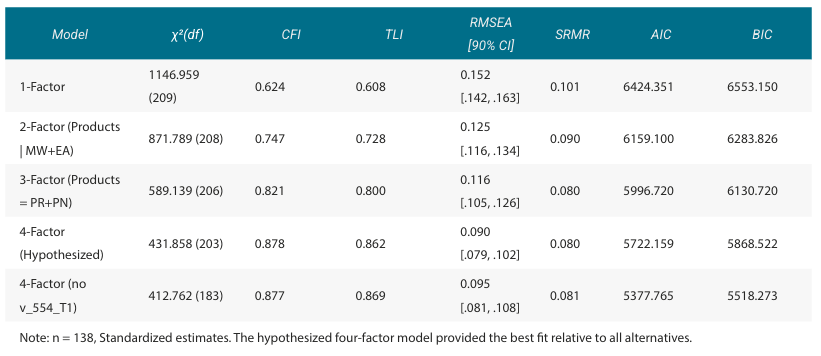

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

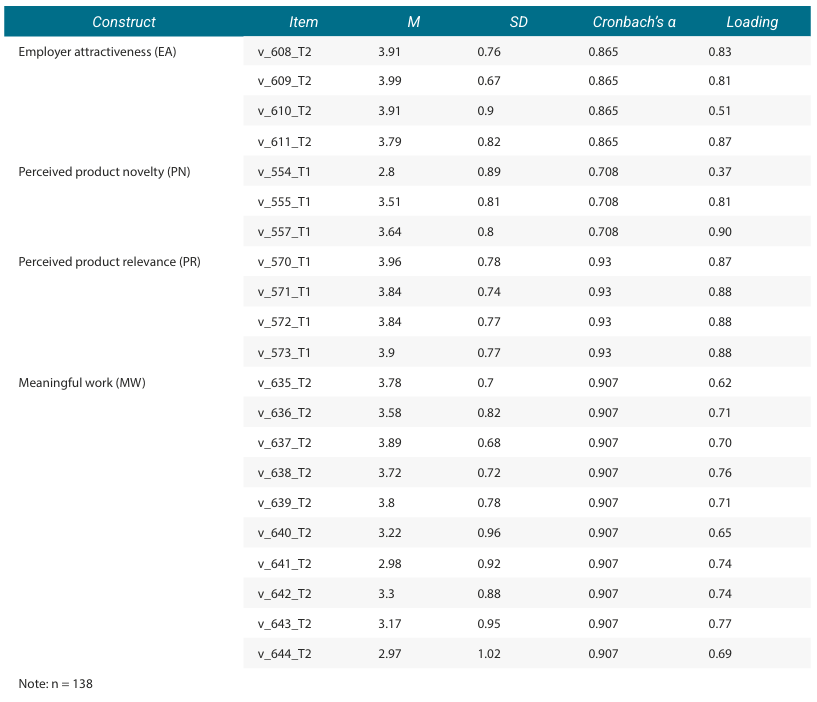

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the lavaan package in R to test the measurement model consisting of four latent constructs: employer attractiveness, meaningful work, perceived product novelty, and perceived product relevance. The model was estimated using maximum likelihood estimation based on a sample of 138 cases. All standardized factor loadings were positive (p < .001), for most items, above recommended threshold of .50; only perceived product novelty (v_554_T1 = .374) showed a marginally lower loading. We decided to retain the full scale for perceived product novelty as originally validated in prior research (Story et al., 2014) to ensure comparability. The remaining loadings ranged from .51 to .89, indicating satisfactory item-factor relationships. Inter-factor correlations were moderate to high (e.g., MW_T2 ~~ PR_T1 = .61; EA_T2 ~~ PN_T1 = .54), supporting convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. All results are reported in Table 2 (see Appendix).

The global fit indices of the CFA model are marginally below conventional cut-offs : χ²(203) = 431.86, p < .001; CFI = .878; TLI = .862; RMSEA = .090 (90% CI [.079, .102]); SRMR = .080. We compared the hypothesized four factor measurement model (employer attractiveness, meaningful work, perceived product novelty, and perceived product relevance) with several alternative structures. A one-factor model (all items loading on a single latent construct), a two-factor model (all product items combined; MW and EA combined), and a three factor model (perceived product novelty and relevance combined) showed substantially poorer fit (CFI < .83, RMSEA > .11). The hypothesized four-factor model (CFI = .878, TLI = .862, RMSEA = .090, SRMR = .080) provided the best representation of the data, outperforming all alternatives (ΔCFI ≥ .05, ΔRMSEA ≥ .03). A robustness test excluding the weakest novelty item (λ = .37) yielded nearly identical results (CFI = .877, TLI = .869, RMSEA = .095). Results are reported in Table 4 (see Appendix).

Our approach is also backed by research raising caution against interpreting CFA thresholds too rigidly, particularly in smaller samples and models with many items. As Shi et al. (2019) demonstrate, traditional fit indices can systematically underestimate model fit under such conditions. In line with their recommendations, we therefore rely on a combination of evidence, including high factor loadings for most items, satisfactory composite reliabilities (CR > .77), and AVE values above 0.50, all of which support the convergent validity of our constructs.

Descriptive statistics

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 29.0.2.0), including mediation analyses performed with the PROCESS macro (Model 4; Hayes, 2018).

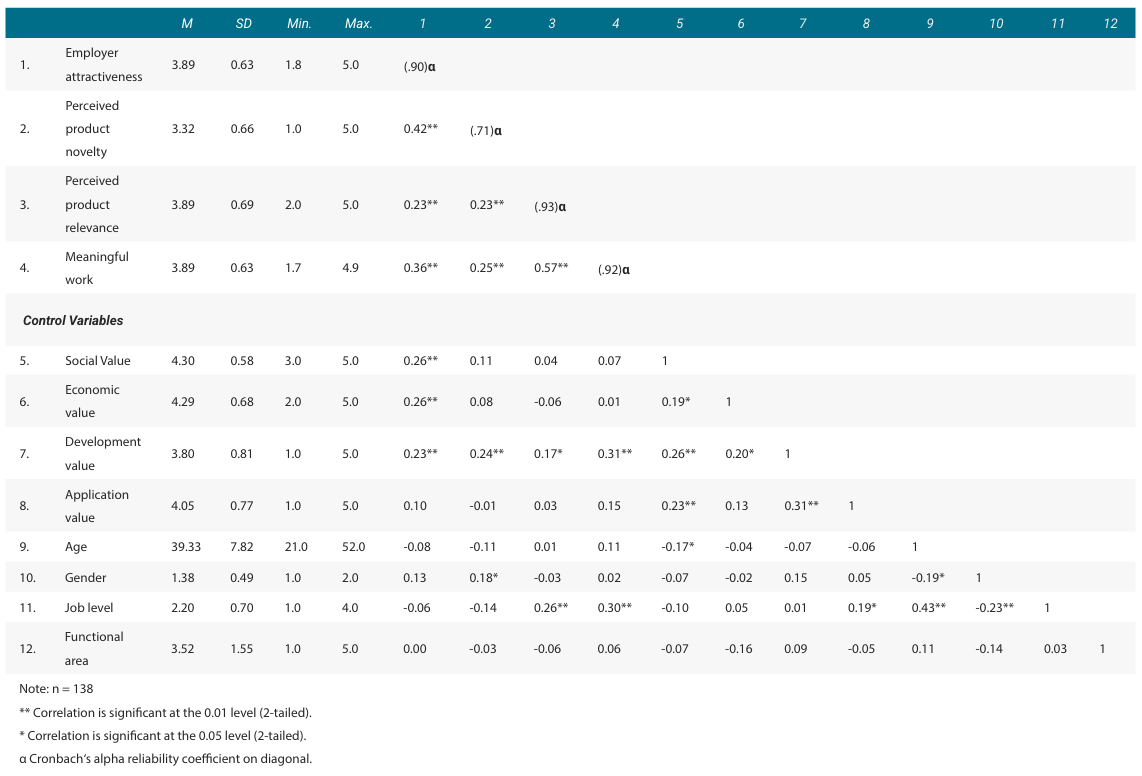

Table 3 (see Appendix) presents descriptive statistics, reliabilities, and correlations among the study variables. Employer attractiveness was positively correlated with perceived product novelty (r = .42, p < .01), perceived product relevance (r = .23, p < .01), and meaningful work (r = .36, p < .01), with the strongest correlation observed for perceived product novelty. Perceived product relevance showed a strong correlation with meaningful work (r = .57, p < .01). Taken together, these results confirm that employer attractiveness is positively related to all central study variables, providing initial support for the hypothesized relationships. Reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for multi-item scales are reported on the diagonal.

Hypothesis testing

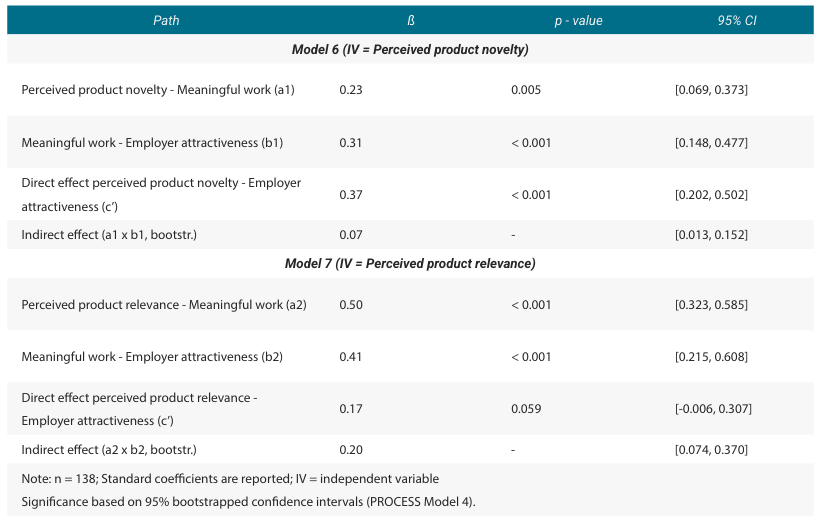

The results of our analysis for the empirical testing of Hypotheses 1-7 are reported in Table 5 and 6 (see Appendix). We test the proposed mediation framework first by using the procedure outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). We then quantify the indirect effects and confidence intervals using a bootstrapping approach (Preacher and Hayes, 2008).

A linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the effects of control variables on perceived employer attractiveness (Model 1). The overall model was significant, F(8, 129) = 2.92, p < .01, and explained approximately 15.3% of the variance in employer attractiveness (R² = .15). The effect of social value (β = .20, p = .024) and economic value (β = .22, p = .012) was significantly positive, while all other control variables were not statistically significant related to perceived employer attractiveness.

In Model 2, perceived product novelty was added as an independent variable, alongside control variables. The overall model was significant, F(9, 128) = 5.39, p < .001, and explained 27.5% of the variance in employer attractiveness (R² = .28). The relationship of perceived product novelty with perceived employer attractiveness was positive and significant (β = .37, p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

In Model 3, perceived product relevance was entered as an independent variable, alongside control variables. The overall model was significant, F(9, 128) = 3.05, p = .002, explaining 17.7% of the variance in perceived employer attractiveness (R² = .18). Perceived product relevance was not significantly related to (β = .17, p = .059). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not supported.

In Model 4, we tested the relationship between perceived product novelty and meaningful work, along with control variables. The overall model was significant, F(9, 128) = 4.48, p < .001, and explained 24.0% of the variance (R² = .24). Perceived product novelty had a significant positive relation to meaningful work (β = .23, p = .005). Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

In Model 5, of the relation of perceived product relevance to meaningful work was examined, along with control variables. The overall model was significant, F(9, 128) = 9.80, p < .001, and explained 40.8% of the variance in meaningful work (R² = .41). Perceived product relevance had a significant and positive relation to meaningful work (β = .50, p < .001). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

In Model 6, we tested the mediation effects of meaningful work in the relationship between perceived product novelty and perceived employer attractiveness, along with control variables. The model was significant, F(10, 127) = 6.76, p < .001, and explained 34.7% of the variance in employer attractiveness (R² = .35). Both perceived product novelty (β = .30, p < .001) and meaningful work (β = .31, p < .001) were significantly related to employer attractiveness. A bootstrapping analysis with 5,000 samples and a 95% confidence interval confirmed a significant indirect effect of perceived product novelty on employer attractiveness through meaningful work (B = .07, SE = .04, 95% CI [.0133, .1519]). Since both the direct and indirect effects were statistically significant, this indicates that meaningful work partially mediates the relationship between perceived product novelty and perceived employer attractiveness and therefore, our results provide partial support for Hypothesis 6.

In Model 7, we tested the mediating effect of meaningful work in the relationship between perceived product relevance and perceived employer attractiveness. The model was significant, F(10, 127) = 4.81, p < .001, and explained 27.5% of the variance in employer attractiveness (R² = .28). Meaningful work was positively and directly related to perceived employer attractiveness (β = .41, p < .001), while the direct effect of perceived product relevance remained to be not significant (β = –.04, p = .680). A bootstrapping analysis (5,000 samples, 95% CI) confirmed a significant indirect effect of perceived product relevance on perceived employer attractiveness via meaningful work (B = .20, SE = .08, 95% CI [.0738, .3704]). These results provide support for Hypothesis 7.

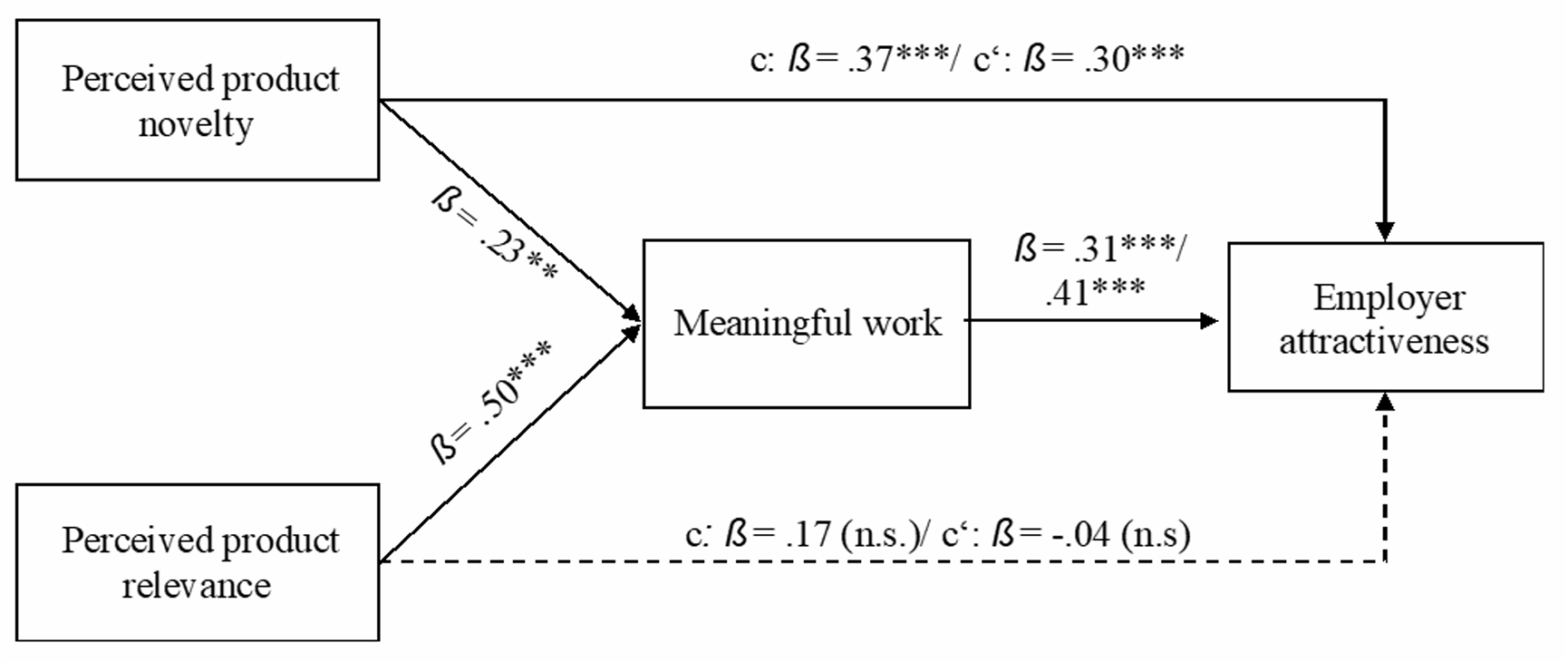

In Model 8, both perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance were entered simultaneously, along with all control variables. The model was significant, F(10,127) = 4.93, p < .001, explaining 28% of the variance in employer attractiveness (R² = .28). The relationship of perceived product novelty with perceived employer attractiveness remained positive (β = .35, p < .001), whereas perceived product relevance was not significantly related to employer attractiveness (β = .08, p = .356). This joint analysis addresses potential omitted-variable bias and indicates that perceived product novelty exerts a unique effect when controlling for perceived product relevance. Our findings are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Mediation model – Impact of product-related characteristics on employer attractiveness

Note: Standardized path coefficients are displayed: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01. Solid lines indicate positive relationships (p < 0.05); dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. c indicate the direct relationship (Models 2,3); c’ indicate the direct relationships with meaningful work as the mediator (Models 6,7).

Discussion

This study examined whether perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance relate to employer attractiveness directly and indirectly through meaningful work. The results showed that perceived product novelty was directly and indirectly positively related to employer attractiveness, while perceived product relevance operated only indirectly through meaningful work. In so doing, this study advances research on employer attractiveness in three main ways as well provide practical implications. First, we extend the literature beyond HR-related factors such as compensation, leadership, or work–life balance (e.g., Tanwar and Prasad, 2017; Dabirian et al., 2019) by showing that perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance—dimensions central in branding research (Aaker, 2004)—also matter for how employees evaluate their employer. Prior work has emphasized symbolic attributes for applicants (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003); our results demonstrate that such product-based signals are also relevant for employees, thereby broadening the scope of internal employer branding.

Second, our study also emphasizes the central role of meaningful work in understanding employer attractiveness. Employees who experience their work as meaningful are more likely to report positive attitudes toward their organization, including stronger identification, engagement, and commitment (Pratt and Ashforth, 2003; Rosso et al., 2010; Steger et al., 2012; Bailey et al., 2019; Allan et al., 2019; Lysova et al., 2019).

In our model, meaningful work is closely related to both perceived product novelty and perceived product relevance, indicating that employees interpret signals of innovation and societal contribution through their sense of purpose at work. Perceived product novelty positively relates to employer attractiveness both directly and indirectly through meaningful work, whereas perceived product relevance related to attractiveness only indirectly via meaningful work. These findings suggest that employees do not simply respond to organizational products as such but make sense of them in terms of how they shape the meaningfulness of their own work, which in turn is associated with perceptions of their employer’s attractiveness.

Third, our study adds empirical evidence from a global B2B chemical company, a context often described as a “dirty industry” that is often associated with environmental concerns and low external appeal (King and Lenox, 2000). By showing that innovation and societal contribution in products can strengthen the internal employer brand even under reputational challenges, we provide a critical test case that complements prior studies conducted primarily in consumer-facing or high-reputation industries. This finding suggests that product-related cues may be particularly important in sectors where traditional HR signals alone are insufficient to attract and retain talent.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

As with any single study, our findings should be interpreted in light of certain limitations, which also open avenues for future research. First, we drew on data from one global chemical company. While this provides a critical case for examining employer attractiveness in a sector often associated with reputational challenges, it limits the generalizability of our findings. Future studies should replicate our model across industries with different reputational profiles, such as consumer goods or services, to assess whether the role of perceived product novelty and relevance varies by context (cf. De Waal, 2018; Dabirian et al., 2019).

Second, our analysis was conducted at the individual level, meaning that we examined employees’ perceptions rather than objective organizational characteristics. As in prior research on employer attractiveness (Lievens and Highhouse, 2003), this focus captures subjective evaluations that are central to understanding how employees experience their employer. At the same time, future research could complement such studies with multi-company or cross-level designs that compare individual perceptions with organizational level practices, thereby linking micro- and macro-level insights.

Third, although the fit indices were marginally below conventional thresholds, the hypothesized four-factor model outperformed all alternative specifications and, together with strong convergent validity (factor loadings, CR, AVE) supports the distinctiveness of the constructs. Given the relatively small sample, these findings should be interpreted as indicative of relationships rather than statistical significance, and future studies should replicate the CFA with larger and more diverse samples to further validate structure (Shi et al., 2019). In addition, longitudinal designs with more than two measurement points would allow researchers to examine how perceptions of novelty and relevance evolve in response to product launches, strategic changes, or sustainability initiatives.

Finally, we treated perceptions of product novelty and relevance as stable constructs. However, employees’ interpretations are likely dynamic and shaped by organizational and external events. Building on sensemaking theory (Weick, 1995), future research could investigate how critical incidents (e.g., product recalls, breakthrough innovations) shape employees’ experience of meaningful work and, in turn, their evaluation of employer attractiveness.

Practical Implications

Our findings provide several actionable insights for organizations seeking to strengthen their internal employer brand. First, for HR managers, the results confirm that symbolic drivers such as perceived novelty and relevance do not substitute traditional HR related factors. Economic and social value continued to significantly predict attractiveness, underscoring the need for competitive compensation, supportive work environments, and development opportunities. Still, HR can enhance the power of these tangible benefits by complementing them with meaningful narratives about how employees’ contributions connect to societal needs through relevant products. In this way, HR integrates “hard” benefits with signals of purpose, thereby reinforcing employees’ identification with the organization.

Second, for product development and innovation teams, the finding that perceived product novelty is strongly related to employer attractiveness highlights that innovation is not only a market advantage but also an internal branding asset. Novel products serve as signals of vitality and future orientation (Spence, 2002). Organizations should therefore not only invest in product development but also make these signals visible internally—for example, by communicating innovation milestones, involving employees in product launches, or creating spaces for employees to experience and celebrate innovation. Such practices increase the likelihood that employees interpret novelty as a source of pride and meaningfulness.

Third, for sustainability and CSR functions, our results suggest that the societal relevance of products only translates into employer attractiveness when it is experienced as meaningful. This implies that managers need to actively communicate the broader purpose of products—through sustainability initiatives, internal communication campaigns, or opportunities for employees to participate in CSR-related activities. Making societal contributions visible at the job level ensures that relevance is not just an abstract claim but a tangible part of employees’ daily work (Aguinis and Glavas, 2019; Glavas and Lysova, 2025). When employees perceive that their work contributes to societal good, signals of product relevance are transformed into meaningful work experiences.

Taken together, these implications suggest that employer branding should be treated as a cross functional responsibility. HR, innovation, and sustainability managers need to collaborate to align product strategy, societal value creation, and employee experience. Products function as organizational signals that must be supported by HR practices and internal communication, so that employees can interpret them as meaningful. This integrated approach is particularly important in industries such as chemicals, where external reputational challenges make internal branding both more difficult and more essential.

Conclusion

This study advances research on employer attractiveness by shifting the focus from applicants to employees. We show that perceived product novelty relates to employer attractiveness both directly and indirectly via meaningful work, while perceived product relevance relates only indirectly through meaningful work. By integrating branding theory, signalling theory, and meaningful work research, we provide a product- and meaning-based perspective on employer attractiveness.

Practically, our findings highlight the importance of aligning product innovation and societal contribution with HR practices to strengthen the internal employer brand. Taken together, our results suggest that employer attractiveness emerges not only from HR-related factors but also from how employees interpret the signals sent by their organization’s products.

References

Aaker, D. A., & Shansby, J. G. (1982). Positioning your product. Business horizons, 25(3), 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(82)90130-6

Aaker, D. A. (2004). Leveraging the corporate brand. California Management Review, 46(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/000812560404600301

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311436079

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2019). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691575

Albinger, H. S., & Freeman, S. J. (2000). Corporate social performance and attractiveness as an employer to different job seeking populations. Journal of Business Ethics, 28(3), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006289817941

Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406

Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

App, S., & Büttgen, M. (2016). Lasting footprints of the employer brand: Can sustainable HRM lead to brand commitment? Employee Relations, 38(5), 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2015-0122

Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430410550754

Bailey, C., Yeoman, R., Madden, A., Thompson, M., & Kerridge, G. (2019). A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 18(1), 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318804653

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. 3514.51.6.1173 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022

Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon.

Dabirian, A., Paschen, J., & Kietzmann, J. (2019). Employer branding: Understanding employer attractiveness of IT companies. IT Professional, 21(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITP.2018.2876980

Dassler, A., Khapova, S. N., Lysova, E. I., & Korotov, K. (2022). Employer attractiveness from an employee perspective: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 911038. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.858217

De Waal, A. (2018). Increasing organizational attractiveness: The role of the HPO and happiness at work frameworks. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 5(2), 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-10-2017-0080

Glavas, A., & Lysova, E. I. (2025). Meaningful work and corporate social responsibility: Examining the interactions of a sense of calling with organizational- and job-level factors. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 98(3), e70045. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.70045

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Highhouse, S., Lievens, F., & Sinar, E. F. (2003). Measuring attraction to organizations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(6), 986–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164403258403

Im, S., Bhat, S., & Lee, Y. (2015). Consumer perceptions of product creativity, coolness, value and attitude. Journal of Business Research, 68(1), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.03.014

Klimkiewicz, K., & Oltra, V. (2017). Does CSR enhance employer attractiveness? The role of millennial job seekers’ attitudes. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(5), 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1419

King, A. A., & Lenox, M. J. (2000). Industry self-regulation without sanctions: The chemical industry‘s responsible care program. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556362

Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00144.x

Lievens, F., Van Hoye, G., & Anseel, F. (2007). Organizational identity and employer image: Towards a unifying framework. British Journal of Management, 18(S1), S45 S59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00525.x

Lysova, E. I., Allan, B. A., Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Steger, M. F. (2019). Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 374–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.07.004

Maurya, K. K., & Agarwal, M. (2018). Organisational talent management and perceived employer branding. International Journal of Organisational Analysis, 26(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-04-2017-1147

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work: An identity perspective. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn

(Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 309–327). Berrett-Koehler.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Reis, G. G., & Braga, B.M. (2016). Employer attractiveness from a generational perspective: Implications for employer branding. Revista de Administração, 51(1), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.5700/rausp1226

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Shi, D., Lee, T., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2019). Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(2),

310–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418783530

Sommer, L. P., Heidenreich, S., & Handrich, M. (2017). War for talents: How perceived organizational innovativeness affects employer attractiveness. R&D

Management, 47(2), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12230

Spence, M. (2002). Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. American Economic Review, 92(3), 434–459. https://doi.org/10.1257/00028280260136200

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160

Story, V. M., Boso, N., & Cadogan, J. W. (2014). The form of relationship between firm-level product innovativeness and new product performance in developed and emerging markets. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12180

Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and validation: A second-order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2015-0065

Theurer, C. P., Tumasjan, A., Welpe, I. M., & Lievens, F. (2018). Employer branding: A brand equity-based literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(1), 155–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12121

Turban, D. B., & Cable, D. M. (2003). Firm reputation and applicant pool characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 24(6), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.215

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672. https://doi.org/10.5465/257057

Uen, J. F., Ahlstrom, D., Chen, S. Y., & Liu, J. (2015). Employer brand management, organisational prestige and employees’ word-of-mouth referrals in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 53(1), 104–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12024

Vnoučková, L., Urban Cova, H., & Smolová, H. (2018). Building employer image thanks to talent programmes in Czech organisations. Inzinerine Ekonomika – Engineering Economics, 29(3), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.29.3.13975

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage

Appendix

Table 1. Date Collection Questionnaire

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Internal Consistency of CFA Items

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Model Fit Comparison

Table 5. Regression Models

Table 6. Mediating effects (Hays Process Model)