Entrepreneurial potential in chemistry and pharmacy. Results from a large survey

Abstract

Nowadays entrepreneurship has become an unavoidable issue. Given its documented relevance for regions’ and countries’ economic growth, increasingly governments, educators, and scientists try to uncover the determinants of entrepreneurship seeking ultimately to promote entrepreneurial skills amongst our youngest. Notwithstanding such trend, studies targeting entrepreneurial potential among students, namely university students are not abundant. In general, those few that exist focus on one school/one course, often from business related areas. To our best knowledge no study has analyzed the entrepreneurial potential of students from chemistry and pharmacy courses. The empirical results, based on a large-scale survey of 2,430 final-year students, 194 of whom are from chemistry (science and engineering) and pharmacy courses at the largest Portuguese university, reveal that the latter have higher entrepreneurial potential than students from other courses and that no statistical difference exists in this regard among chemistry and the other students (excluding those from pharmacy). In chemistry and pharmacy courses the main determinant of entrepreneurial potential is students’ propensity for risk taking. Creativity, leadership and innovative traits failed to explain these students entrepreneurial propensity. In an economic environment which increasingly demands for novelty and creativity this is likely to constitute a troublesome finding and is an important point to be addressed both by policy makers and educators.

1 Introduction

The idea of becoming an entrepreneur is more and more attractive to students because it is seen as a valuable way of participating in the labor market without losing one’s independence (Martínez et al., 2007). The most common values amongst graduates facing the new labor market are linked to those of the self-employed: independence, challenge and self-realization (Lüthje and Franke, 2003).

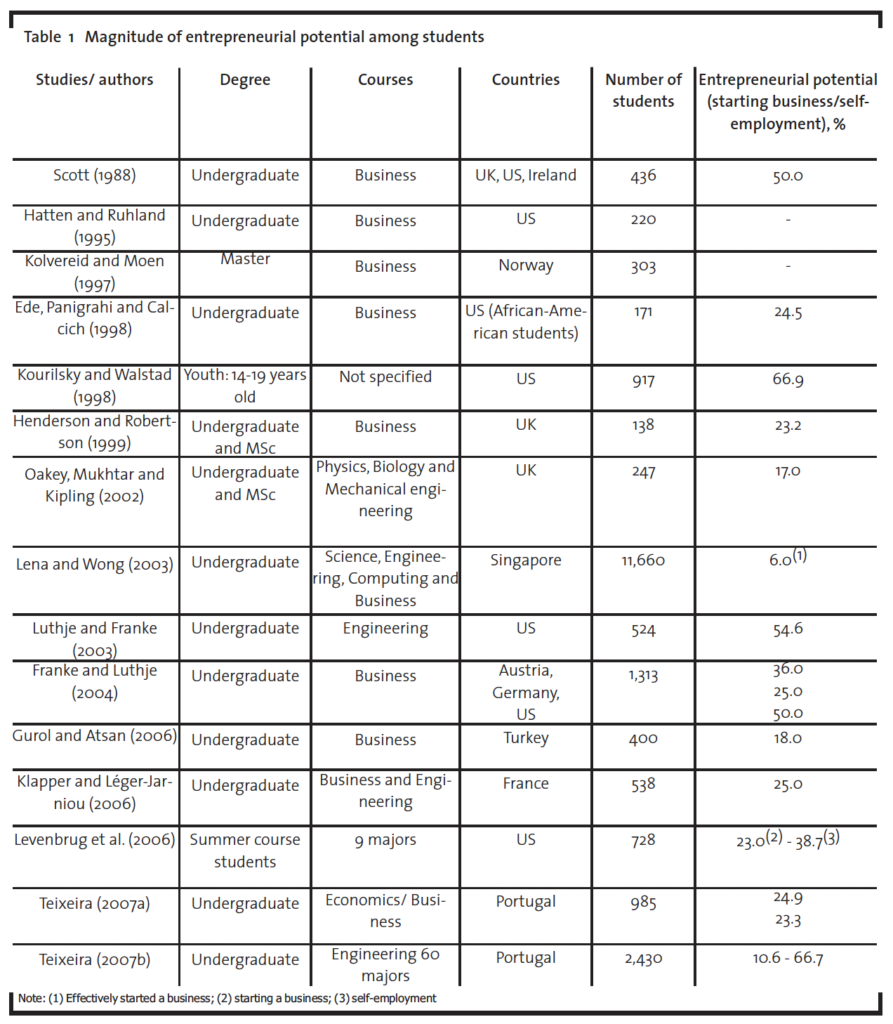

While there has been significant research on the causes of entrepreneurial propensity (Brandstatter, 1997; Greenberger and Sexton, 1988; Learned, 1992; Naffziger et al., 1994), only a limited number of studies have focused on the entrepreneurial intent among students. Those that exist tend to focus on US and UK cases and are mainly restricted to small samples of business related majors (cf. Table 1).

Despite the heterogeneity of sampling methods and target population, the existing studies on the issue (see Table 1) report that, on average, one quarter of students surveyed claimed that after their graduation they would like to become entrepreneurs (starting their own business or being self-employed). It is not widely known (and is currently subject to intense debate) whether contextual founding conditions or personal traits drive the students’ career decision towards selfemployment (Lüthje and Franke, 2003). In order to design effective programs, policy makers have to know which of these factors are decisive (Scott and Twomsey, 1988).

While new venture opportunities exist within nearly all academic disciplines (e.g., graphic arts, nursing, computer science, chemistry and pharmacy), the majority of entrepreneurship initiatives at universities are offered by business schools (Ede et al., 1998; Hisrich, 1988) and for business students (e.g., Roebuck and Brawley, 1996). In fact, most studies that have been conducted to explore entrepreneurial intent among university students have focused on business students (e.g., DeMartino and Barbato, 2002; Ede et al., 1998; Hills and Barnaby, 1977; Hills and Welsch, 1986; Krueger et al., 2000; Lissy, 2000; Sagie and Elizur, 1999; Sexton and Bowman, 1983). However, Hynes (1996) advocated that entrepreneurship education can and should be promoted and fostered among non-business students as well as business students. Picker et al. (2005) refer that entrepreneurial led measures have been recently implemented, through the establishment of new graduate programs, in the Cambridge-MIT Institute, the Stockholm School of Entrepreneurship, and the International Graduate School of Chemistry (Münster, Germany). Consequently, if a goal in designing entrepreneurial programs is to assist students within and outside the business school, it is important to understand students enrolled in other majors that not business.

The aims of the present paper are threefold: first, to examine the magnitude of entrepreneurial intention among final year students (namely comparing students of chemistry related majors (bio-chemistry, chemistry science, chemistry engineering) and pharmacy with students of the remaining courses); second, to explain students entrepreneurial intentions, that is to assess the relevance of potential determinants (demographic, psychological and context) influencing the entrepreneurial intention and again test for the (eventual) differences in this regards between students of chemistry related majors (bio-chemistry, chemistry science, chemistry engineering) and pharmacy and the remaining students; third, to analyze the relationship between courses and students’ interest in further education on entrepreneurship.

The paper is structured as follows. In the following section a brief review of the literature on students’ entrepreneurial intentions is presented. Then, in Section 3, we detail the methodology and describe the data. The estimation model and results are presented in Section 4. Some conclusions are summarized in Section 5.

2 Student entrepreneurship potential. A brief review of the literature

The traditional mainstream view of the entrepreneur is as a ‘risk-taker’ bringing different factors of production together. The Austrian school takes a more dynamic perspective with entrepreneurship crucial for economic development and as a catalyst for change. In particular the Schumpeterian entrepreneur is an innovator who introduces new products or technologies. Frequently the notion of entrepreneurship is associated with predominant characteristics such as creativity and imagination, self-determination, and the abilities to make judgmental decisions and coordinate resources (Henderson and Robertson, 1999). Adapting Carland et al.’s (1984: 358) definition of “entrepreneur”, we define ‘potential entrepreneur’ as “an individual [final year student] who [admits] establish[ing] and manag[ing] a business for the principal purposes of profit and growth”.

According to several authors (e.g., Carland et al., 1984; Hatten and Ruhland, 1995), entrepreneurs are characterized mainly by innovative behavior and employment of strategic management practices in the business.

A relevant body of literature on entrepreneurial activities reveals that there is a consistent interest in identifying the factors that lead an individual to become an entrepreneur (Martínez et al., 2007). Several pieces of evidence show that these are similar, with the most frequent analyzed as age, gender, professional background, work experience, and educational and psychological profiles (Delmar and Davidsson, 2000).

Broadly, three factors have been used to measure entrepreneurial tendencies: demographic data, personality traits (Robinson, 1987), and contextual factors (Naffziger et al., 1994). Demographic data (gender, age, region) can be used to describe entrepreneurs, but most of these characteristics do not enhance the ability to predict whether or not a person is likely to start a business (Hatten and Ruhland, 1995). The second method of assessing entrepreneurial tendencies is to examine personality traits such as achievement motive, risk taking, and locus of control. McClelland (1961) stressed need for achievement as a major entrepreneurial personality trait, whereas Robinson (1987) asserted that self-esteem and confidence are more prominent in entrepreneurs than the need for achievement. Several authors (e.g., Naffziger et al., 1994), however, argue that the decision to behave entrepreneurially is based on more than personal characteristics and individual differences. Accordingly, the interaction of personal characteristics with other important perceptions of contextual factors needs to be better understood.

Dyer (1994) developed a model of entrepreneurial career that included antecedents that influenced career choice. Antecedents to career choice included individual factors (entrepreneurial traits), social factors (family relationships and role models), and economic factors. This author asserted that children of entrepreneurs are more likely to view business ownership as being more acceptable than working for someone else. Baucus and Human (1995) studied Fortune 500 firm retirees who started their own business and found that networking, their view of departure, and prior employment experience positively affected the entrepreneurial process. Carroll and Mosakowski (1987) asserted that children with selfemployed parents likely work in the family firm at an early age. That experience, coupled with the likelihood of inheriting the firm, led the individuals to move from a helping situation to full ownership and management. Van Auken et al. (2006) found that the importance of family owned businesses and the influence of family (including parental role modeling) in Mexico suggests that Mexican students may be more interested in business ownership than US students. Earlier, Scott (1988) also found that children of self-employed parents have a much higher propensity to become self-employed themselves. He conjectured that perhaps the influence of parents was twofold: first, as occupational role models, and second, as resource providers.

In Section 4, for the selected students, we assess which of the three groups of determinants of entrepreneurial intention – demographic, psychological, and contextual – emerges as more relevant. Before embarking on this analysis, the next section details and describes the methodology and data gathered.

3 Methodology and descriptive statistics

A questionnaire was developed and pre-tested during spring 2006. Final year students of all subjects at the largest Portuguese university (Universidade do Porto) were surveyed regarding their entrepreneurial potential. The survey was mainly conducted in the classroom, but when that was impossible (some final year students did not have classes as they were in internship training), the survey was conducted through an online inquiry. The final year students totaled 3,761 individuals, spread over 60 courses, offered by 14 schools/faculties. The survey was carried out from September 2006 up to March 2007. A total of 2,430 valid responses were gathered, representing a high response rate of 64.6%. Of these responses, 107 were from chemistry related majors (bio-chemistry, chemistry science, and chemistry engineering), and 87 from pharmacy (totaling 194 individuals). The response rates of these groups were, respectively 80.6% and 70.7%. The questionnaire contained 17 questions, which include a specific demographic descriptors (such as gender, age, student status, and region); participation in extra curricula activities, professional experience, academic performance, and social context; statements designed to measure fears, difficulties/obstacles and success factors concerning new venture formation to which students responded using a 5-point Likert scale.

The entrepreneurial potential or intent was directly assessed by asking students which option they would choose after completing their studies: starting their own business or being exclusively selfemployed; to work exclusively as an employee; to combine employment and self-employment. Although such procedure is widely and extensively used in the literature on this subject (see, for instance, Scott, 1988; Ede et al., 1998; Lüthje and Franke, 2003; Franke and Lüthje, 2004; Gurol and Atsan, 2006), it is important to point out the potential bias that it might involve as we are basing our argument on a general statement to a possible action in future.1 It would probably be more accurate to examine our research questions by employing an ex-post observation (e.g. 5 years later when these students are entrepreneurs or employees), but this would constitute not a measure of entrepreneurial intent but rather a measure of effective entrepreneurial behaviour. Moreover, to have such measure would require cohorts of students, which was not materially possible at this stage of the research.

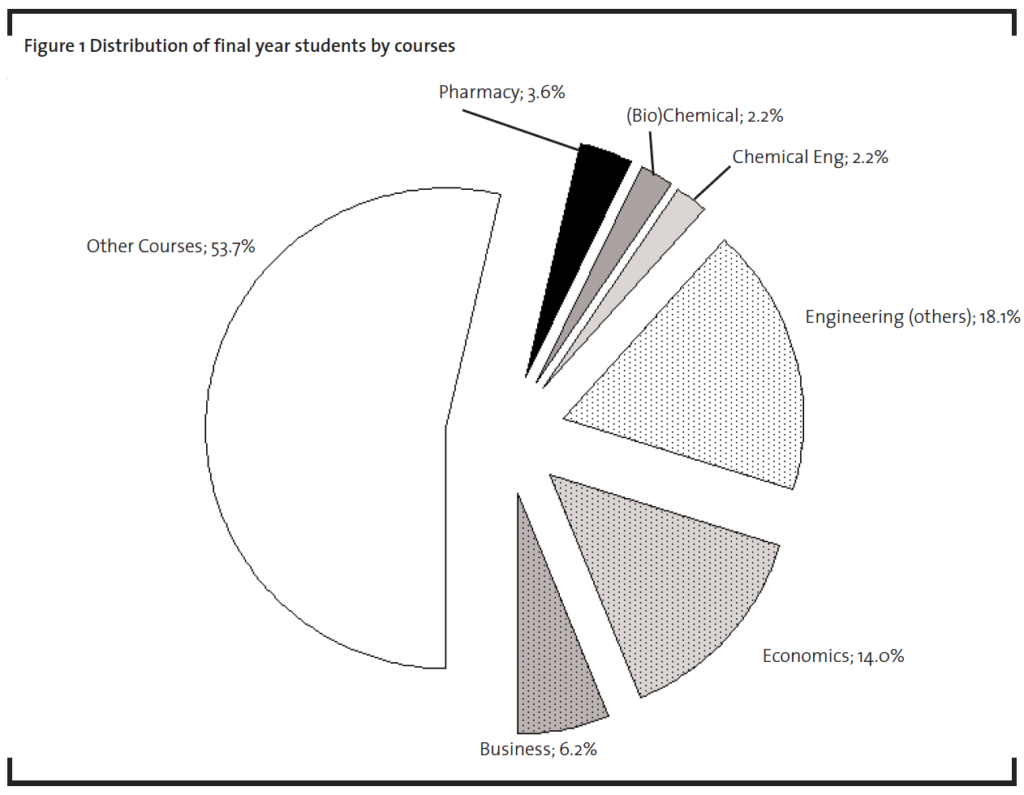

Chemistry and Pharmacy related courses account for 8% of total respondent sample. This is a small percentage when compared with other courses 14% of respondents are from Economics course and 6.2% from Business; in engineering the most representative courses are Computing, Electronics and Civil engineering, encompassing, respectively, 4.5%, 3.5% and 3.4% of the total number of selected students. Nevertheless, such percentages fairly represent the whole population.

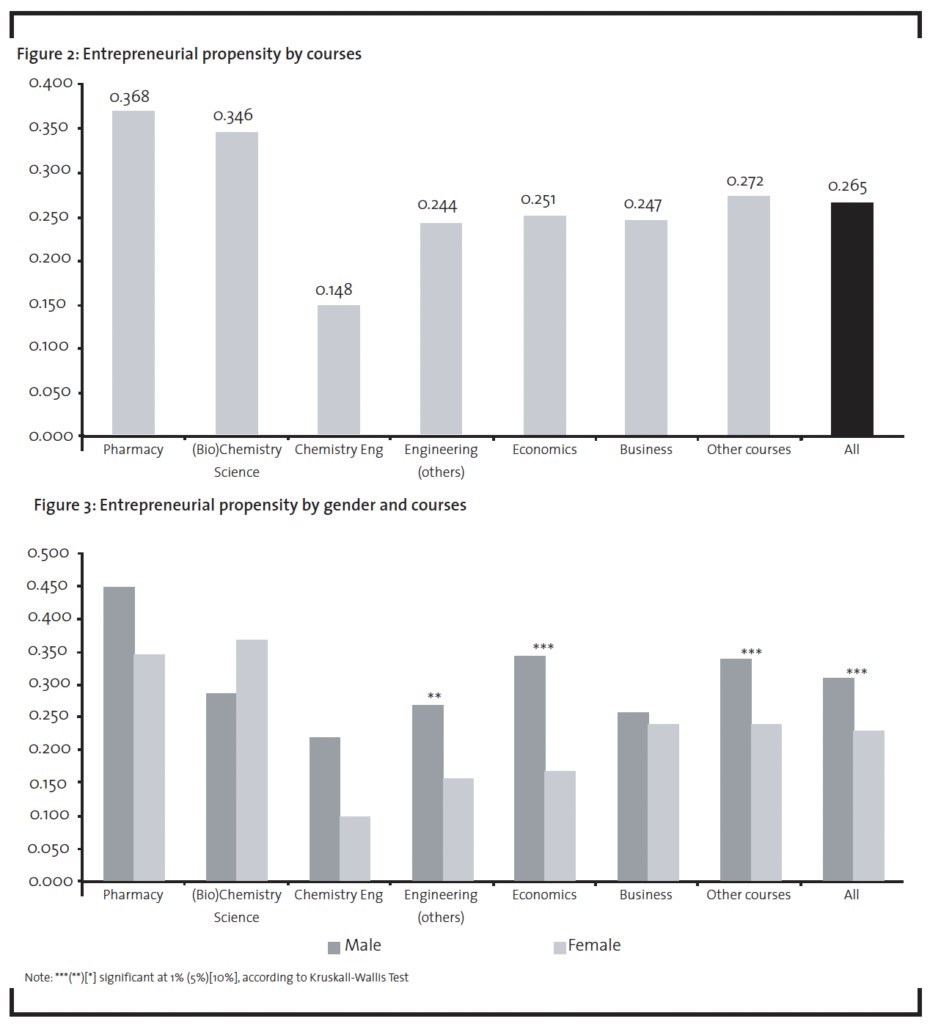

On average, 34.6% of (bio)chemistry science students surveyed claim that they would like to start their own business after graduation, a much higher value than that of chemistry engineering students (14.8%). Pharmacy students are the most entrepreneurial led – on average, 36.8% would desire to become entrepreneurs after graduation.

It might, at first glance, be puzzling the wide difference between Pharmacy/(Bio) Chemical Science and Chemistry Engineering. Industry’s entry barriers and labour market issues might be relevant for explaining such evidence. In pharmacy and chemical science the most probable employment outlet are (Commercial) Drugstores and Chemical Labs. Although the regulation entry barriers are not negligible, financial/capital entry barriers are relatively low compared with other types of industry (Portugal-Autoridade da Concorrência, 2005), namely chemistry engineering related industries. Moreover, in Portugal, chemistry engineering jobs convey a relatively high entry salary and the employment rate is low (Portugal, 2004), which might discourage entrepreneurial intents.

It is interesting to note that, in general, male students are statistically significant (using KruskalWallis test) more entrepreneurially driven than their female counterparts 31% of male students would like to start their own business after graduation, whereas in the case of female students, that percentage is around 23%. Differences by course are particularly acute in Economics and Other Engineering courses. In Pharmacy and Chemistry related courses there is no evidence that statistical significant differences exist. A remarkable exception to the overall pattern – male more entrepreneurial than female students is (Bio)Chemistry, where 37% of the female students claimed to desire start their own business after graduation against 29% of the male counterparts. Nevertheless, such difference failed to reveal statisticall significance.

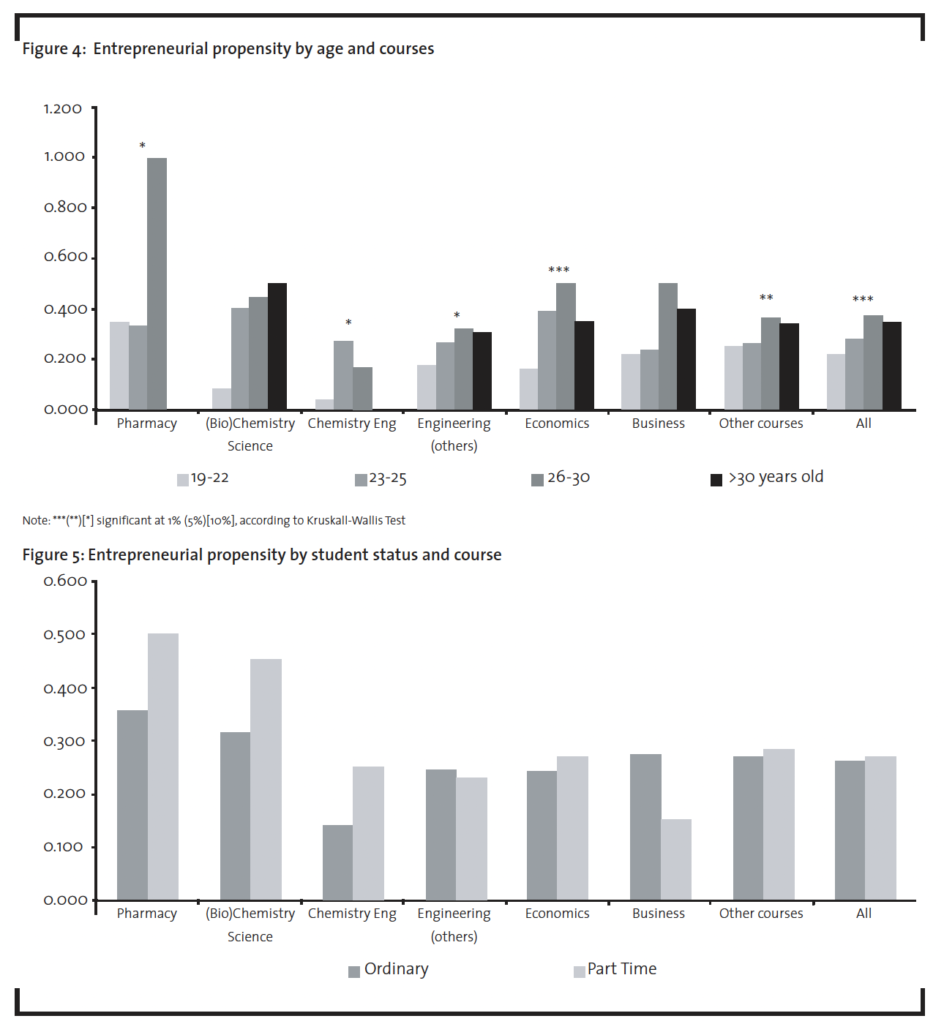

In general, older students (over 26 years old) are more entrepreneurial than their younger colleagues. Differences between age groups are particularly evident in Economics whereas in Pharmacy and Chemistry related courses differences are not statistically significant.

At first sight, there seems to be a relationship between the status of the student, namely to be involved in academically related issues (student association members) or professional occupation – part time status – and the desirability to be an entrepreneur in pharmacy and chemistry related courses. Notwithstanding, the differences are not statistically significant. Figure 5 shows that the status for the whole sample does not discriminate between entrepreneurial led and other students.

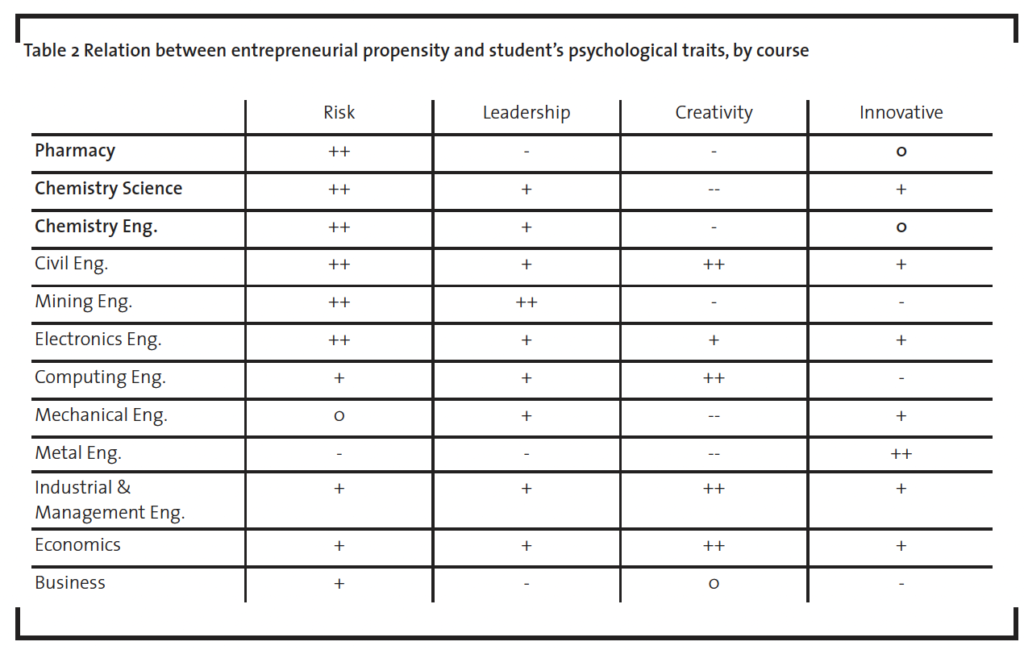

Correlating entrepreneurial potential with some psychological attributes associated with an entrepreneur (cf. Section 2) – risk taking, no fear of employment instability and uncertainty in remuneration; leadership wishes; creative focus; and innovative focus – we obtain an interesting picture by course.

Risk taking behavior was computed by considering the scores of the four items regarding the fear associated with new business formation – uncertainty in remuneration; employment instability; possibility to fail personally; possibility of bankruptcy. Firstly, dummies were computed for each item attributing 1 when the student responded small or no fear. Then we added up the four dummies and computed a new one which scored 1 if the sum variable totaled 3 or 4.

Today’s businesses, workers, and educational institutions are making large investments in identifying and developing a personal characteristic called leadership. Some studies (e.g., Kuhn and Weinberger, 2005) identify ‘potential leaders’ as those students who reported that, within a given period, they were team captain or club presidents. Although we recognize that this might constitute a reasonable proxy, in the Portuguese university context these high school leadership activities are quite inexpressive. Thus, we devise an alternative proxy, based on the future desired occupation as employee. Baker and Aaron (1999) found evidence that one of the main skills associated to Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) occupations is leadership. Accordingly, we consider ‘potential leaders’ students that chose the option ‘Directors/CEOs’ (of firms or other organizations) when asked which occupation they would aspire in the case they were employees after graduation. In other words, leadership is a binary variable that assumes the value 1 when students identify Director as his/her future desired occupation (in case they were employee) and 0 otherwise.

Creativity is becoming more valued in today’s global society (Florida, 2005). As in leadership, in the case of creativity behaviour, the proxy was based on students’ answers to the future desired occupation. However, the occupation based procedure used here relies on Richard Florida’s (2002) measure of creative class. Florida’s work proposes that a new or emergent class, or demographic segment made up of knowledge workers, intellectuals and various types of artists is an ascendant economic force, representing either a major shift away from traditional agricultureor industry-based economies, or a general restructuring into more complex economic hierarchies. The creative class is a class of workers whose job is to create meaningful new forms. The creative class is composed, for instance, of scientists and engineers, university professors, poets and architects. Their designs are widely transferable and useful on a broad scale, as with products that are sold and used on a wide scale. Another sector of the creative class includes those positions which are knowledge intensive (Florida, 2005; Boschma and Fritsch, 2007). While by no means perfect, the procedure undertaken here enables, based on students indication of what type of occupation they would choose in case they opted by working as employees after graduation, to have a (rough) indicator of students’ creativity potential/trait. In operational terms, creativity assumes the value 1 when students’ future desired occupation is classified (in the taxonomy described above) as a creative occupation and 0 otherwise.

The literature concerning innovation-related classifications of industries is surprisingly scant and tends to be dominated by the Pavitt’s (1984) taxonomy and the OECD’s popular High-tech/Lowtech dichotomy. This OECD’s has recently been applied with regard to the concept of Knowledge based Economy (KBE). The notion of KBE revolves around the tripod “use-production-distribution of knowledge”. The OECD (1999) has focused on the first leg of this tripod and has not only adopted a working definition of knowledge-based sectors based on the intensity of inputs of technology and human capital but also has empirically identified the set of knowledge-based sectors. The OECD defines knowledge-based sectors as “those industries which are relatively intensive in their input of technology and/or human capital”, and identifies the set of knowledge-based sectors with High-technology industries, Communication services, Finance insurance, real estate and business services, and Community, social and personal services (OECD, 1999: 18). Based on this study, we categorize sectors by degree of technology intensity and knowledge intensity. Thus, in the case students refer a sector classified as ‘high techhigh knowledge intensive’ (cf. OECD taxonomy), the variable ‘innovation’ assumed the value 1 and 0 otherwise.

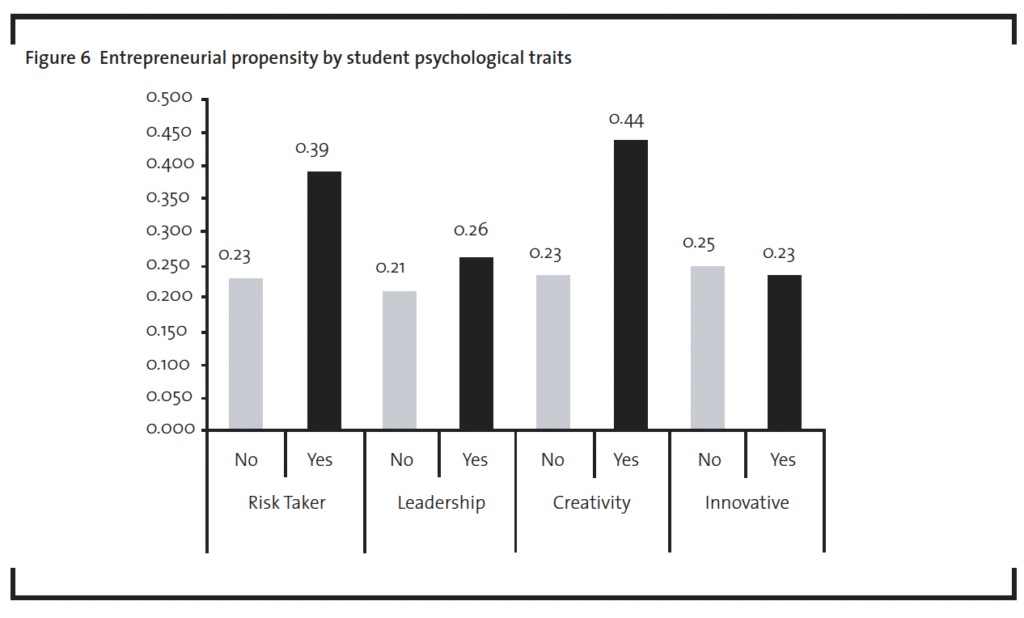

As it is apparent in Figure 6, considering the whole sample, risk taker students (‘Yes’) present, on average, a higher entrepreneurial potential than their non-risk taker (‘No’) colleagues 39% of students with risk taker behaviour would like to start a business after graduation whereas in the case of non-risk taker students the corresponding figure is only 23%. For creativity this difference is also substantial – 44% of students classified as having creativity behaviours (‘Yes’) are potential entrepreneurs whereas for non creativity prone students (‘No’) the corresponding percentage is almost halved. Leadership and innovative behaviors do not seem to discriminate between potential entrepreneurs, albeit in the case of leadership, students with this trait (‘Yes’) are more likely to aspire to become an entrepreneur after graduation.

For our baseline courses – pharmacy, chemistry science and chemistry engineering students’ traits differ in what respect leadership and innovativeness, but are similar regarding risk propensity and creativity. More specifically, we observe that in these courses, students that present a higher entrepreneurial propensity are, on average, riskier but less creative than their lower entrepreneurial led colleagues. Concerning leadership we might point that this is a trait of entrepreneurial led students of Chemistry (science and engineering) but not from those of Pharmacy. Finally, innovativeness emerges as a characteristic of Chemistry science students that are entrepreneurial led, whereas in Pharmacy and Chemistry Engineering the propensity to entrepreneurship does not differ between innovative and non-innovative students.

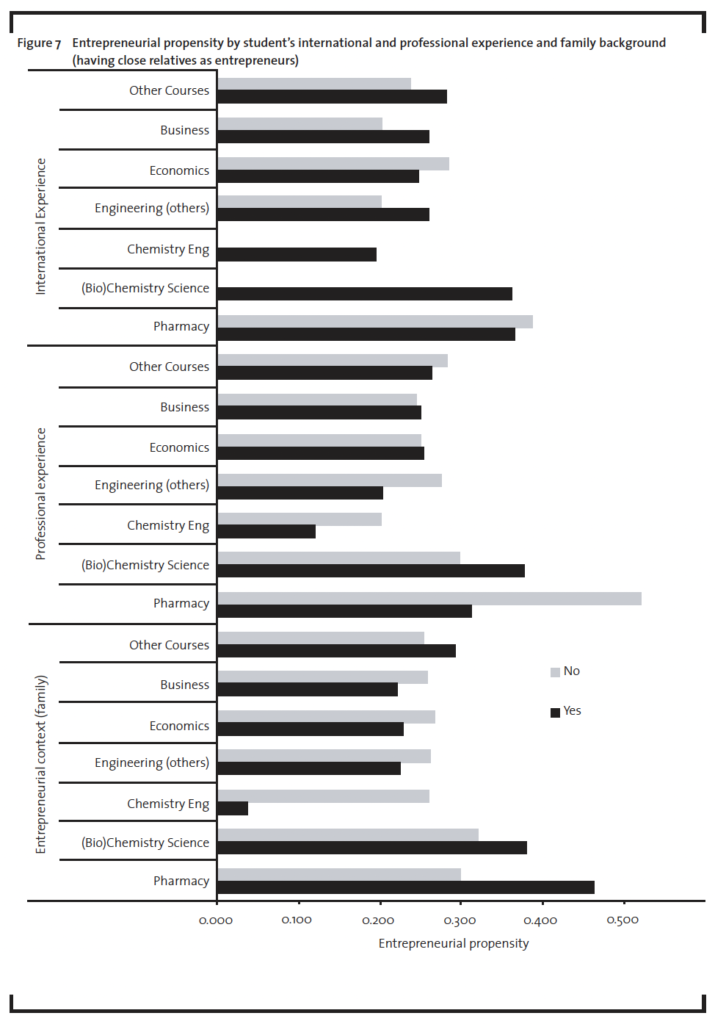

In courses such as Economics, Civil Engineering, Electronics, and Industrial and Management Engineering, students presenting higher risk behavior, leadership traits, focus on creativity and innovative sectors reveal, on average, higher entrepreneurial potential. Nevertheless, risk behavior is associated with low entrepreneurial propensity in Mechanical and Metal courses; in Business and Metal Engineering leadership traits are essentially associated with non entrepreneurs; creativity is negatively associated with entrepreneurial potential in Mining, Mechanical, Metal and Chemical industries, which, given their business focus, is not really surprising. More surprising is the fact that focus on innovative sectors is not associated with entrepreneurial propensity in the Computing course. The role of experience at the level of associations, and other extra curricula activities, having international experiences, and professional activity experience is mixed with regard to entrepreneurial potential. Only in Economics and Pharmacy is the entrepreneurial propensity positively correlated with students’ international experience. Regarding the professional experience, those students that claimed to have (had) a paid job tend to be more entrepreneurial led in Chemistry engineering and other engineering as well in pharmacy courses. Family models (to have close relatives entrepreneurs) are particularly important, that is, seems to be highly (positively) correlated with students entrepreneurial potential in Chemistry engineering and (in a lesser extent) in Business, Economics and other engineering courses.

4 Estimation model and results

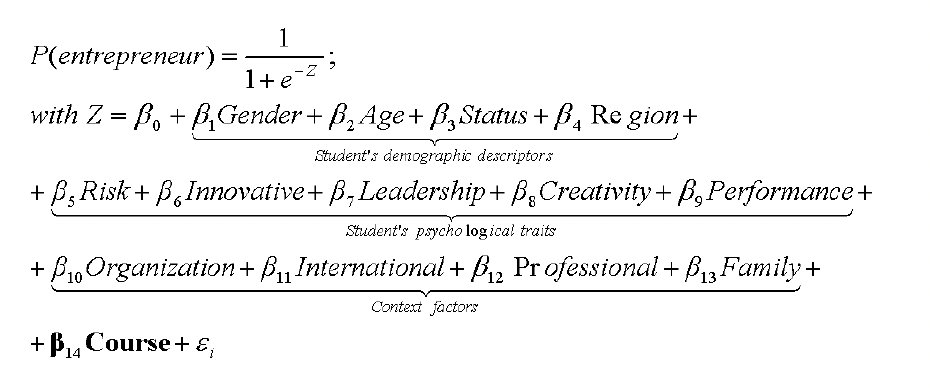

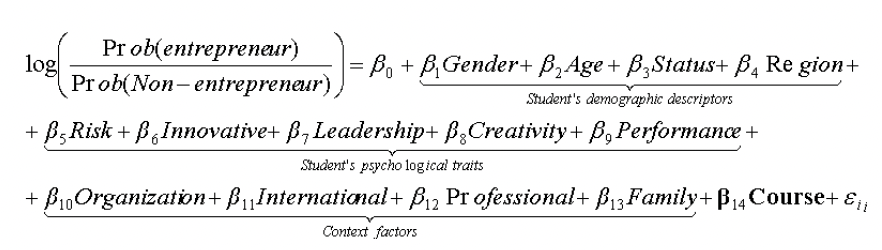

The aim here is to assess which are the main determinants of the student’s entrepreneurial propensity. The nature of the data observed relative to the dependent variable [Opt to start a business after graduation? (1) Yes; (0) No] dictates the choice of the estimation model. Conventional estimation techniques (e.g., multiple regression analysis), in the context of a discrete dependent variable, are not a valid option. First, the assumptions needed for hypothesis testing in conventional regression analysis are necessarily violated – it is unreasonable to assume, for instance, that the distribution of errors is normal. Second, in multiple regression analysis, predicted values cannot be interpreted as probabilities – they are not constrained to fall in the interval between 0 and 1. According to the literature (cf. Section 2) there is a set of factors, such as student’s demographic descriptors (gender, age, student status, and region of residence), psychological traits (risk, leadership, innovative and creative focus, and academic performance), and context factors (participation in extra curricula activities, international experience, professional experience, and family background), and university course. The empirical assessment of the propensity to contact is based on the estimation of the following general logistic regression:

In order to have a more straightforward interpretation of the logistic coefficients, it is convenient to consider a rearrangement of the equation for the logistic model, in which the logistic model is rewritten in terms of the odds of an event occurring. Writing the logistic model in terms of the odds, we obtain the logig model:

The logistic coefficient can be interpreted as the change in the log odds associated with a one-unit change in the independent variable.

Then, e raised to the power βi is the factor by which the odds change when the ith independent variable increases by one unit. If βi is positive, this factor will be greater than 1, which means that the odds are increased; if βi is negative, the factor will be less than one, which means that the odds are decreased. When βi is 0, the factor equals 1, which leaves the odds unchanged. In the case where the estimate of β1 emerges as positive and significant for the conventional levels of statistical significance (that is, 1%, 5% or 10%), this means that, on average, all other factors being held constant, female students would have a higher (log) odds of entrepreneurial potential.

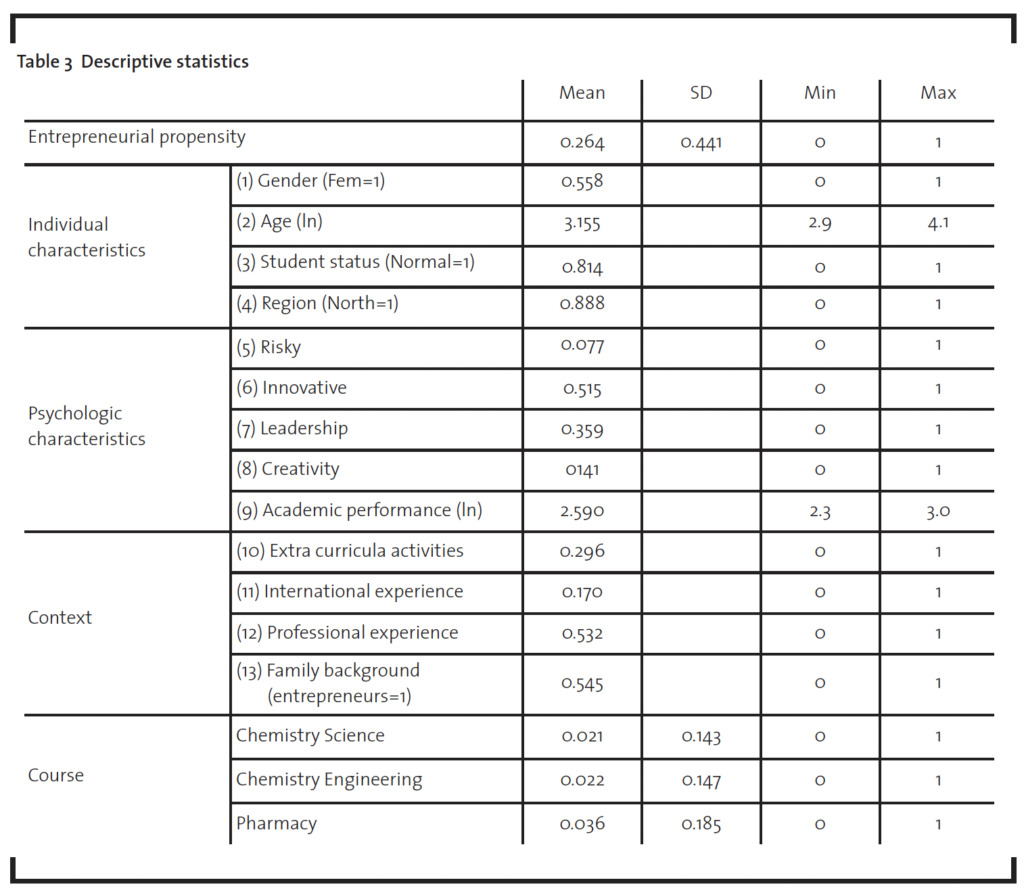

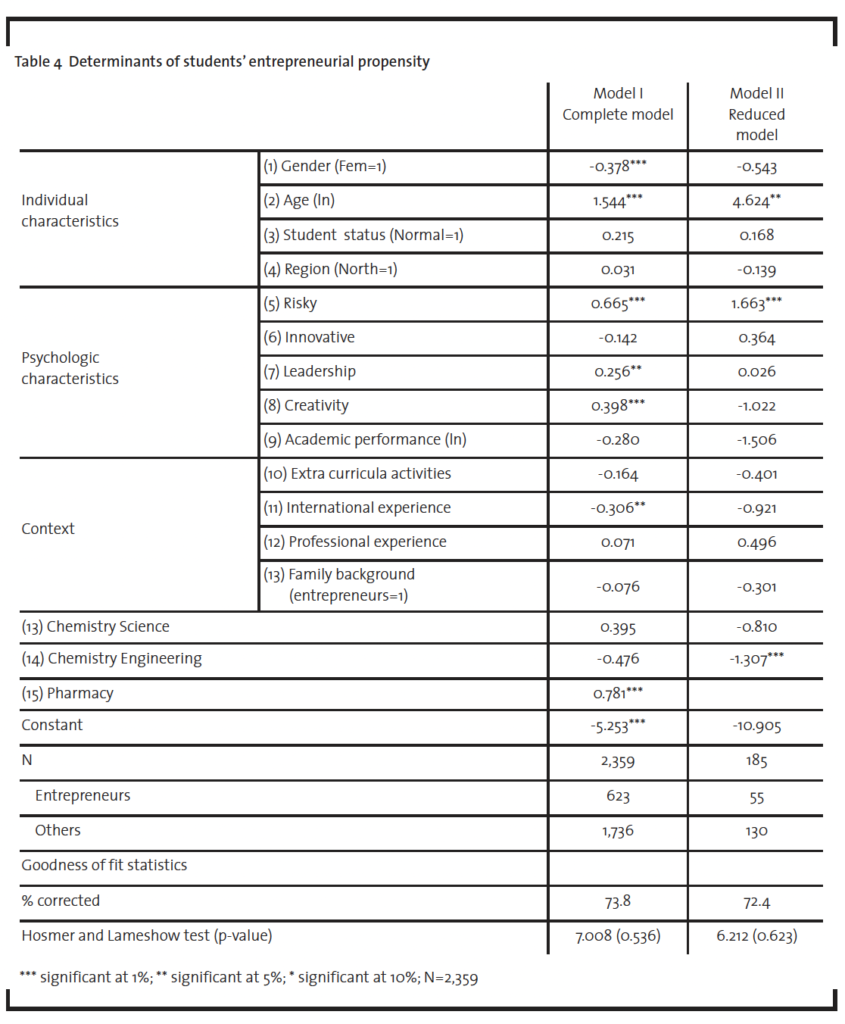

The estimates of the βs are given in Table 4. In this table we present two different models. The first model illustrates the estimated econometric specification relative to students of all (60) courses, grouping them into Chemistry Science, Chemistry Engineering, Pharmacy and Others courses (the default category). The second model restricts the sample to Chemistry Science, Chemistry Engineering, and Pharmacy students, considering Pharmacy course the default category. In Table 3, some descriptive statistics of the variables involved in the estimation procedure, as well their bivariate linear correlations estimates, are presented.

Considering all (2,431) final year students, on average, 26.4% stated that after graduation they would like to start their own business or be exclusively self-employed.

Around 56% are female and have an average age of 23. The vast majority (over 80%) are ordinary students and live in the North region.

Only a small percentage of students (8%) may be classified as risk prone (no or little fear of employment instability, uncertainty in remuneration, and failure).

Over a third (35.9%) present a leadership conduct, admitting that if they could choose an occupation, they would like to be firm’s or other organization’s directors/CEOs. Although 51.5% would invest in high-tech or high knowledge intensive industries in the event of starting a new business, only 14.1% would invest in creative industries.

On average, students present a reasonable academic performance (with an expected grade of 13 out of 20), the majority (53.2%) have or had some professional activity, 29.6% were or are involved in extra curricula activities, and a few (17%) had some sort of international experience (e.g., Erasmus mobility program). More than half (54.5%) have close relatives that are entrepreneurs.

As we referred earlier, Chemistry science, Chemistry engineering and Pharmacy encompass, respectively 2.1%, 2.2% and 3.6% of total students. In Model I, which includes (2,359) students from 60 majors, females reveal a much lower propensity for entrepreneurship than their male colleagues. Such gender differences are not evident in the restricted model, that is, when we consider only students from Chemistry science, Chemistry engineering and Pharmacy courses. Whereas the first result ties in with other studies (e.g., Martínez et al., 2007), which indicate that entrepreneurship activities are more related to males, the second result finds some echo with the earlier study of Ede et al. (1998), who found no difference between male and female African American students in their attitudes toward entrepreneurship education.

All other characteristics and determinants being constant, and similarly to Ede et al. (1998), more senior students are more likely to be a potential entrepreneur. Student status only emerges as a relevant determinant of entrepreneurial propensity for the restricted model. However, the estimate indicates that among business/economics and engineering students, normal or ordinary students (i.e. full-time students) tend to be more entrepreneurially driven. Regional origin of the students does not seem to impact on the propensity which might be at least in part be explained by the fact that the vast majority (almost 90%) live in the North (the region where the University of Porto is located).

In the complete model (Model I), psychologically related factors, such as risk propensity, leadership behavior and creativity focus, emerge as critical for explaining students’ entrepreneurial intent. In these competences the scores of potential entrepreneurs are much higher than those of the remaining students. When we restricted the sample of students to Chemistry science, Chemistry engineering and Pharmacy courses, the only psychological trait that remain statistically (and positively) significant is risk. This result corroborates our previous analysis (Table 2) and underlines that for these types of courses creativity, leadership, and innovative features might not be determinant for starting new ventures. Nevertheless, this might be worrisome if one takes for granted that the new tendency for business creation in general, and chemistry in particular (EPSRC, 2006), requires creativity and innovation.

The expected average grade does not explain the entrepreneurial propensity of students both in the complete and restricted models. Surprisingly, almost none of the contextual factors turn out to be relevant. In contrast to some previous evidence (e.g., Martínez et al., 2007), potential entrepreneurs do not differ from other students in the time they spend on other activities. Controlling for individual and psychological factors, potential entrepreneurs and others spend a similar amount of time working to acquire professional experience, and on extra curricula activities. Moreover, the role model stressed by the literature concerning the importance of family and contextual background does not prove to be important in this study. We do not confirm, therefore, the results of other entrepreneurship studies (Brockhaus and Horwitz, 1986; Brush, 1992; Cooper, 1986; Krueger, 1993), which found that students from families with entrepreneurs have a more favorable attitude toward entrepreneurship than those from non-entrepreneurial backgrounds.

Finally, controlling for all the variables likely to impact on entrepreneurial propensity, Model I shows that Pharmacy students are more prone to entrepreneurial intents than students from other majors such as economics, business, and (other) engineering, to name just a few. This result proves to be quite unfortunate given the focus that previous studies on entrepreneurship placed on these two majors, and the fact that a substantial part of entrepreneurial education is undertaken in business schools (Levenburg et al. 2006). Additionally, differences emerge (Model II) between Chemistry Engineering and Pharmacy majors with regard to entrepreneurial propensity – students of Chemistry engineering tend to be much less entrepreneurial led than their colleagues from Pharmacy. At least in part, as we referred earlier, such difference might be explained by industries characteristics (relatively low regulation and financial/capital entry barriers in pharmacy retail distribution) and labour market issues (relatively high entry salary and low employment rates for chemistry engineers).

5 Conclusions

In this paper, the entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduates in Portugal are examined along with their related factors. The findings have insightful implications for researchers, university educators and administrators as well as government policy makers.

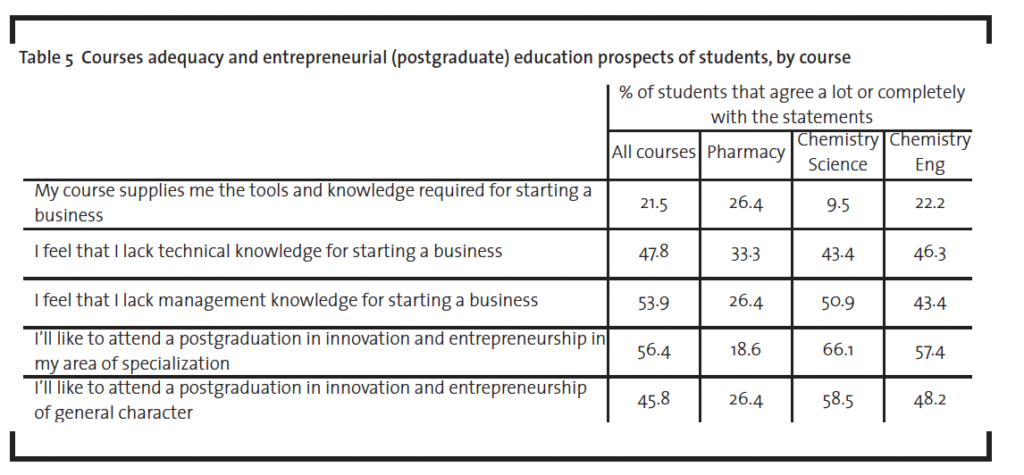

First, the entrepreneurial propensity of undergraduates of Pharmacy and (Bio)Chemistry Science is quite high (around 35%), well above the Portuguese and other European (Germany and Austria) countries averages (around 25%). Notwithstanding, the corresponding figure is extremely low (15%) in Chemistry Engineering. Second, for the whole sample, two demographic factors – gender and age – and three psychological traits – risk, leadership, creativity are found to significantly affect interests in starting one’s own business, while contextual factors, such as family background, are found to have little independent effect. In the case we restrict the sample to Pharmacy and (Bio)Chemistry Science, and Chemistry Engineering only age and risk propensity emerge as significant determinant of entrepreneurial potential. Creativity, leadership and innovation seems not to be a characteristics of (potential) entrepreneurs in Pharmacy and Chemistry related courses, which given the worldwide economic features of business creation is likely to constitute a quite worrisome evidence. Although a reasonable amount of students of Pharmacy and Chemistry (Science) would like to run their own businesses, their intentions are hindered by inadequate preparation. A substantial percentage of students (90% in Chemistry Science, and over 70% in Pharmacy) recognize that their course failed to supply them the required knowledge and tools for starting a business. Moreover, excluding Pharmacy, between 50%60% of students are aware that their technical and (especially) business knowledge is insufficient for starting a business.

Excluding students from Pharmacy, the vast percentage (around 60% or more) of students, particularly in Chemistry related courses, would like to attend further studies in innovation and entrepreneurship targeting their area of specialization.

We do agree with Hatten and Ruhland (1995) and Kent (1990) when they claim that more people could become successful entrepreneurs if more potential entrepreneurs were identified and nurtured throughout the education process. They demonstrate that students were more likely to become entrepreneurs after participation in an entrepreneurially related program. In this context, and as Kolvereid and Moen (1997) suggest, entrepreneurship, at least to some extent, might be a function of factors which can be altered through education.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the former and present Rectors of the Universidade do Porto (UP), respectively, Prof. Novais Barbosa and Prof. Marques dos Santos, the Deans of the 14 Schools of the University, and professors/lecturers for their support for this research. Thanks also to José Mergulhão Mendonça (FEP Computing Center), Luzia Belchior (FEP) and André Rosário (MIETE Master Student) for their valuable assistance in the implementation of the survey. A word of profound recognition to all students of UP that participated in the survey.

References

Baker, H., Aaron, P. (1999), Career Paths of Corporate CFOs and Treasurers Financial, Practice and Education, 9(2), p. 38-50.

Baucus, D. , Human, S. (1995), Second-career entrepreneurs: A multiple case study analysis of entrepreneurial processes and antecedent variables, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 19(4), p. 41–72.

Boschma, R., Fritsch, M. (2007), Creative Class and Regional Growth – Empirical Evidence from Eight European Countries, Jena Economics Research Papers, no 2007066, Max-Planck-Institute of Economics.

Brandstätter, H. (1997), Becoming an entrepreneur a question of personality structure?, Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, p. 157-177.

Brockhaus, R. H. Jr., Horwitz, P. S. (1986), The psychology of the entrepreneur, in: Sexton D.L., Smilor R.W.(Eds.), The art and science of entrepreneurship, p. 25-48. Cambridge. MA: Ballinger Publishing.

Brush, C. (1992), Research of women business owners: past trends, a new perspective, future directions, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16, p. 5-30.

Carland, J. W., Hoy, F., Boulton, W. R., Carland, J. (1984), Differentiating entrepreneurs from small business owners: A conceptualization, Academy of Management Review, 9, p. 354-359.

Carroll, G., Mosakowski, E. (1987), The career dynamics of self-employment, Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, p. 570–589.

Cooper, A. (1986), Entrepreneurship and high technology, in: Sexton, D. , Smilor, R. (Eds.), The art and science of entrepreneurship (p. 153-180), Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing.

Delmar, F., Davidsson, P. (2000), Where do they come from? Prevalence and characteristics of nascent entrepreneurs, Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 12, p. 1–23.

DeMartino, R., Barbato, R. (2002), An Analysis of the Motivational Factors of Intending Entrepreneurs, Journal of Small Business Strategy, 12(2), p. 26-36.

Dyer, W. G. (1994), Toward a theory of entrepreneurial careers, Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, 19(2), p. 7-21.

Ede, F. O., Panigrahi, B., Calcich, S. E. (1998), African American students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship, Journal of Education for Business, May-June, 73(5).

EPSRC (2006), Chemistry Programme, Analytical Science Summer School Workshop held on 2 November 2006, Jury’s Inn, Birmingham.

Florida, R. (2002), The Rise of the Creative Class. And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure and Everyday Life. Basic Books.

Florida, R. (2005), The Flight of the Creative Class. The New Global Competition for Talent. HarperBusiness, Harper-Collins.

Franke, N., Lüthje, C. (2004), Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students: A Benchmarking Study, International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 1(3), p. 269-288.

Greenberger, D. B., Sexton, D. L. (1988), An interactive model of new venture creation, Journal of Small Business Management, 26(3), p. 107.

Gürol, Y., Atsan, N. (2006), Entrepreneurial characteristics amongst university students: some insights for enterprise education and training in Turkey, Education and Training, 48(1), p. 25-39.

Hatten, T. S., Ruhland, S. K. (1995), Student attitude toward entrepreneurship as affected by participation in an SBI program, Journal of Education for Business, 70(4), p. 224227.

Henderson, R., Robertson, M. (1999), Who wants to be an entrepreneur? Young adult attitudes to entrepreneurship as a career, Education & Training, 41(4/5), p. 236246.

Hills, G. E., Barnaby, D. J. (1977), Future entrepreneurs from the business schools: Innovation is not dead, in: Proceedings of the 22nd International Council for Small Business (p. 27–30). Washington, DC: International Council for Small Business.

Hills, G. E., Welsch, H. (1986), Entrepreneurship behavioral intentions and student independence, characteristics and experiences, in: Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research: Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Babson College Entrepreneurship Research Conference (p. 173–186). Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

Hisrich, R. D. (1988), Entrepreneurship: Past, present, and future, Journal of Small Business Management, 26(4), p. 1– 4.

Hynes, B. (1996), Entrepreneurship education and training: Introducing entrepreneurship into non-business disciplines, Journal of European Industrial Training, 20(8), p.10–17.

Kent, C. A. (1990), Introduction: Educating the heffalump, in: Kent, C. A. (Ed.), Entrepreneurship education: Current developments, future directions (p. 1-27). New York: Quorum.

Klapper, R., Léger-Jarniou, C. (2006), Entrepreneurial intention among French Grande École and university students: an application of Shapero’s model, Industry & Higher Education, April, p. 97-110.

Kolvereid, L., Moen, Ø. (1997), Entrepreneurship among business graduates: does a major in entrepreneurship make a difference?, Journal of European Industrial Training, 21(4), p. 154.

Kourilsky, M. L., Walstad, W. B. (1998), Entrepreneurship and female youth: Knowledge, attitudes, gender differences and educational practices, Journal of Business Venturing, 13, p. 77 88.

Krueger, N. (1993), The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability, Entrepreneurship theory and practice, Fall, p. 521.

Krueger, N., Reilly, M., Carsrud, A. (2000), Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions, Journal of Business Venturing, 15, p. 411–432.

Kuhn, P., Weinberger, C. (2005), Leadership Skills and Wages, Journal of Labor Economics, July 2005, 23(3), p. 395-436.

Learned, K.E. (1992), What happened before the organization? A model of organization formation, Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 17(1), p. 39–48.

Lena, L., Wong, P. K. (2003), Attitude towards entrepreneurship education and new venture creation, Journal of Enterprising Culture, 11(4), p. 339-357.

Levenburg, N., Lane, P., Schwarz, T. (2006), Interdisciplinary Dimensions in Entrepreneurship, Journal of Education for Business, May-June, p. 276-281.

Lissy, D. (2000), Goodbye b-school, Harvard Business Review, 78(2), p. 16–17.

Lüthje, C., Franke, N. (2003), The ‘Making’ of an Entrepreneur: Testing a Model of Entrepreneurial Intent among Engineering Students at MIT, R&D Management, 33, p. 135147.

Martínez, D., Mora, J.G., Vila, L. (2007), Entrepreneurs, the Self-employed and Employees amongst Young European Higher Education Graduates, European Journal of Education, 42(1), pp.

McClelland, D.C. (1961), The Achieving Society, Van Nostrand, Princeton, NJ.

Naffziger, D.W., Hornsby, J.S., Kurtako, D.F. (1994), A proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), p. 29-42.

Oakey, R., Mukhtar, S-M., Kipling, M. (2002), Student perspectives on entrepreneurship: observations on their propensity for entrepreneurial behaviour, 2(4/5), p. 308-322.

OECD (1981), Science and Technology Policy for the 1980s, Paris.

OECD (1999), OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 1999. Benchmarking Knowledge-Based Economies, OECD: Paris.

Pavitt, K. (1984), Sectoral Patterns of Technical Change: Towards a Taxonomy and a Theory, Research Policy, 13, p. 343-373.

Picker, V., Hahn, L., Vala, M., Leker, J. (2005) Why are scientists not managers!?, Journal of Business Chemistry, 2 (1), p. 1-3.

Portugal,P.(2004),Mitosefactossobreomercadodetrabalho português: a trágica fortuna dos licenciados, Banco de Portugal / Boletim Económico / Março.

Portugal-Autoridade da Concorrência (2005), Decisão da Autoridade da Concorrência CCENT. 40/2004 – OCP Portugal / Soquifa.

Robinson, P. B. (1987), Prediction of entrepreneurship based on attitude consistency model. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Brigham Young University. Dissertation Abstracts International, 48, 2807B.

Roebuck, D. B., Brawley, D. E. (1996), Forging links between the academic and business communities, Journal of Education for Business, 71, p. 125-128.

Sagie, A., Elizur, D. (1999), Achievement motive and entrepreneurial orientation: a structural analysis, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(3), p. 375-387.

Scott, A. J. (1988), New Industrial Spaces, London: Pion. Scott, M.G., Twomey, D.F. (1988), The long-term supply of entrepreneurs: students’ career aspirations in relation to entrepreneurship, Journal of Small Business Management, p. 5-13.

Sexton, D.L., Bowman, N.B. (1983), Comparative entrepreneurship characteristics of students: preliminary results, in Hornaday, J., Timmons, J., Vesper, K. (Eds), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, Babson College,Wellesley, MA, p.213-232.

Teixeira, A.A.C. (2007a), Beyond economics and engineering: the hidden entrepreneurial potential, mimeo, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto.

Teixeira, A.A.C. (2007b), From economics, business and engineering towards law, medicine and sports: a comprehensive survey on the entrepreneurial potential of university students, Paper presented at the Economics Seminar at EEG, Universidade do Minho, 30 March 2007.

Van Auken, H., Stephens, P., Fry, F., Silva, J. (2006), Role model influences on entrepreneurial intentions: A comparison between USA and Mexico, Entrepreneurship Management, 2, p. 325–336.