Multidisciplinary collaborations in pharmaceutical innovation: a two case-study comparison

Abstract

Multidisciplinary collaborations are increasingly predominating innovative industries facing complex challenges. Yet, too frequently managers fail to identify the appropriate situations in which collaborations can be efficient, as their dynamics are not fully investigated. We examine multidisciplinary collaborations, their pertinent agents and complementary network capabilities in the context of the pharmaceutical industry. We focus on three research issues: a) how do multidisciplinary partnerships operate in the pharmaceutical industry? b) at what level are they most relevant (e.g. for knowledge external to the company, or internal)? c) what are the main challenges and benefits of multidisciplinary collaborations?

We analyzed empirical data from two different innovative pharmaceutical firms: a global top-ten corporation based in UK and an international firm located in a small/medium European economy. Our research is using a comparative case study design, drawing strongly from the literature. This research design provides a strong empirical grounding for a rich, in-depth, understanding of multidisciplinary collaborations in the pharmaceutical R&D process, with strong focus on the nature of internal and external partnerships and their impact in the organization.

The findings indicate that innovation management is increasingly reliant on multidisciplinary organizational arrangements; attention to complementary network and agent-related externalities has become vital for the success of the pharmaceutical company. Good managerial practice for multidisciplinary practice is more complex and nuanced than the literature may indicate and relies on flexible, adaptive and contextual processes.

1 Introduction

No man, no society, no institution is an island, existing in solitude from other human beings, societies or institutions. Collaborations among human beings have been the main means of facing everyday challenges and difficulties since the beginnings of our civilization. Corporations are no exception. When facing a challenge an organization will put together employees in a collaborative team to solve the issue. It is often tempting though to see all challenges as similar in nature, They are not. When the organization faces a simple problem that is typical for a particular discipline then they will use methods and approaches that are agreeable within that particular community of practice. The approach is often the best one as the experts know how to handle such an issue and the results of such efforts are often seen as “incremental” (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Romm, 1997; Saur-Amaral, 2005).

However, as technology advances and corporations face novel organizational challenges, resolving these emergent challenges may require diverse human resources that can move across technologies and disciplines. Thus, increasingly, organizations adopt multidisciplinary approaches in their collaborations (hereinafter MDCs), especially in industries where the innovation context is complex and challenging. Managers responsible for such collaborations should duly consider how multidisciplinary collaborations can be utilized effectively and comprehend the strengths and weaknesses of the MDC approach in order to pre-empt any negative side effects (Caruso & Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999).

Some weaknesses of multidisciplinary approaches are: a) take more time than disciplinary approaches, especially in the beginning b) have a higher probability of team conflicts and c) are often characterized by communication problems (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999).

However, MDCs can be more efficient in response to complex challenges that cross several disciplines and need testing and original, idiosyncratic methods to solve emerging issues. MDCs may lead, in principle, to innovation, and thus higher profit margins. Furthermore, are often associated with “radical” innovation and knowledge creation (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005).

Our paper examines MDCs in a complex, innovative industry: pharmaceuticals. The choice of this industry is pragmatic, as the preliminary systematic literature review and the subsequent RefViz analysis on multidisciplinarity (detailed in section 4) indicated that more than half of all records identified in ISI Current Contents and Proquest databases on MDCs are related to the pharmaceutical industry.

This was a sensible result as pharmaceutical industry is a knowledge-intensive multidisciplinary industry, with a large proportion of sales spent on research and development (R&D). R&D is vital in conferring the key competitive factor for the big pharmaceutical innovators: the development of novel drugs as fast as possible, leading to a patent that provides a legal monopoly for the corporation. Drug development is performed with external and internal collaborations, within a multidisciplinary context (Attridge, 2007; Atun and Sheridan, 2007; Kofinas and Saur-Amaral, 2008; Saur-Amaral, 2009; Saur-Amaral and Borges Gouveia, 2007).

We thus aim to understand:

- how do multidisciplinary partnerships operate within the pharmaceutical industry?

- at what organizational levels are they most relevant (for example: absorbing knowledge external to the company, or sharing knowledge internal to the company)?

- what are the main challenges and benefits of multidisciplinary collaborations? The paper is organized as follows. After this introduction, we present the methodology used to perform our research.

In the third section we present key insights from the literature review: The concept of multidisciplinarity (and how it differs from disciplinarity/ interdisciplinarity) and the concept of MDCs (which led us to the concept of network capability).

In the fourth section we examine the results obtained from the empirical study, we utilize a multiple (two) holistic case-study (Yin, 2003) that analyses in depth the role of multidisciplinary partnerships and network capabilities in pharmaceutical innovation.

In the fifth section, we discuss the findings and show how cases validate and enrich the patterns discussed in the existing literature. The fact that they are significantly distinct in research routines, in size, internal organization, R&D structure, yet reveal similarities in the way they manage MDCs indicates validity and partial universality to our findings.

In the sixth section, we look at the nature and operations of MDCs in the pharmaceutical industry and consider some good managerial practices that might be applicable in other pharmaceutical companies or other innovative industrial sectors. We end with conclusions.

2 Methodology

In order to analyze multidisciplinary partnerships in pharmaceutical innovation, we adopted a twofold strategy.

First, we performed a thorough review of existing papers published between 1998 and 2007 on this topic that were included in ISI and Proquest databases. Our search looked at papers referring to MDCs (alliances, partnerships or networks). The most relevant papers were selected and thoroughly analyzed to inform our literature review, clarify the basic concepts, and build the coding taxonomy used for the empirical sections. We used as a methodological tool the bibliographic analysis software RefViz, which enabled us to increase comprehension of key topics related to MDCs theory. The results of this process are presented in section 3 of this paper.

Second, we did two in-depth holistic case studies (Gomm, Hammersley, and Foster, 2004a, 2004b; Yin, 2003). We used the literature review to inform and build a predefined coding structure (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 1998). The coding structure was embedded in an NVivo 7.0 file and each author performed a qualitative analysis on the data to draw the the case reports.

We focused on two cases:

- A bioinformatics department of a global top-ten pharmaceutical multinational based in UK (PharmaCo), and

- An international firm located in a small medium European economy, top-20 pharmaceutical firm in its national pharmaceutical market (PharmaEU).

The choice of these two cases was motivated by the proximity and access to the sites, as well as by the distinct contributions they would make to this research agenda (Gomm, et al., 2004a). We were aiming for a wide range of possible insights, originating from the high degree of difference between the in-depth holistic case studies chosen. The fact that they are significantly distinct in research routines, in size, internal organization, R&D structure, any similarities and insights identified would increase the validity and replicability of our findings and thus attribute a validity and partial universality to our insights in MDC management. Results of this process are presented in section 4 and section 5 of this paper.

3 Multidisciplinarity, multidisciplinary partnerships and network capabilities

3.1 Multidisciplinarity concepts

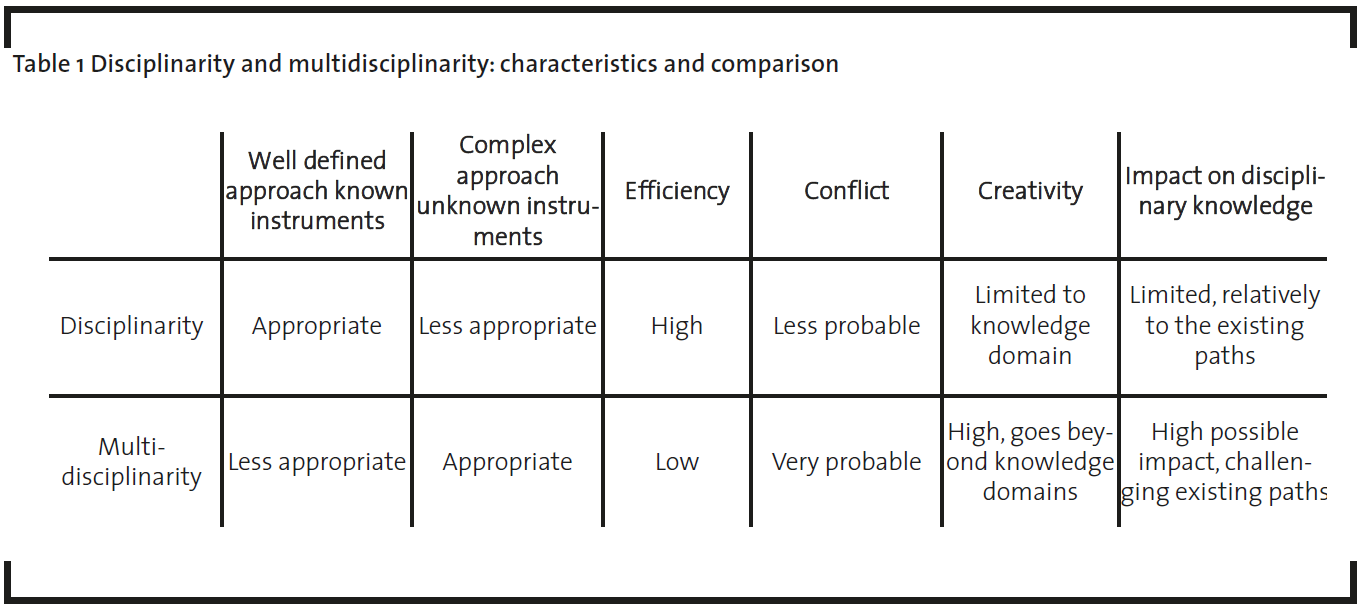

The concepts of disciplinarity, multidisciplinarity (MD), and interdisciplinarity (ID) have been used frequently in the; literature but they are often nebulously defined. To avoid misinterpretations we aim in Table 1 to summarize the differences between the two approaches.

From our point of view, disciplinarity involves a well-specified knowledge domain, with fairly well-defined boundaries, within which specialists share cultural and conceptual frameworks (Roper and Brookes, 1999; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005). These specialists use common methods and instruments and they play by the rules established within the respective community of practice (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Roper and Brookes, 1999; Saur-Amaral, 2005). Disciplinary collaborations seem to be more efficient when based on diagnosis and application of agreed instruments and problem-solving techniques. However, scholars have argued that disciplinary collaborations may be less creative (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Romm, 1997; Saur-Amaral, 2005).

Multidisciplinarity implies there are specialists from two or more disciplines that work together for a specific objective. Usually, the objective is more complex and challenging, in the sense that it is located on the boundaries of a specific discipline, or even beyond such boundaries. In such cases, there are no agreed conventions and instruments applicable to solve the challenge, and there is a need for creative solutions and experimentation, which can be detrimental to efficiency (Nissani,1999; Romm, 1997; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005). In addition, MDCs often have to overcome communication hurdles and have to deal with frequent conflicts, management and coordination problems (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Chiesa and Toletti, 2004; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999). In the literature, the term Interdisciplinarity (transdisciplinarity) is often used as a synonym to multidisciplinarity are often used in the literature, while select authors present them as separate concepts (e.g. Bruce, Lyall, Tait, and Williams, 2004). Interdisciplinarity falls at the crossing of various disciplines, and interdisciplinary enterprises are in that sense similar to multidisciplinary ones. However, an interdisciplinary enterprise evolves and changes the original disciplines it originated from and leads to new methods, instruments, and work practices. The final outcome is a new discipline formed to cover a prior gap and may lead to other disciplinary – multidisciplinary – interdisciplinary cycles of knowledge evolution. An example of interdisciplinary research would be human robotics, where scientists from biology and mechanics, just to name two disciplines, work together to achieve common goals (Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005).

Thus, an enterprise that creates a new discipline can be seen as a multidisciplinary enterprise that evolves into an interdisciplinary enterprise (Bruce, et al., 2004; Saur-Amaral, 2005). In our study, we focus on multidisciplinary collaborations, in the sense defined in the above paragraphs.

3.2 Multidisciplinary partnerships and network capabilities

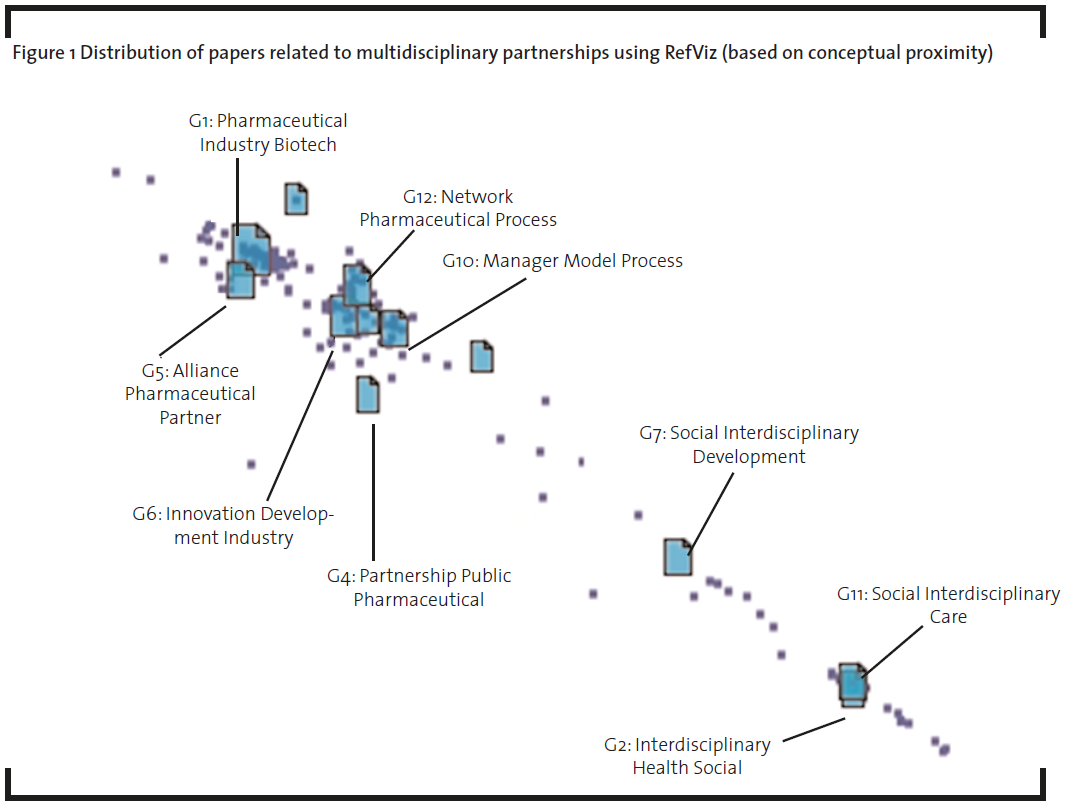

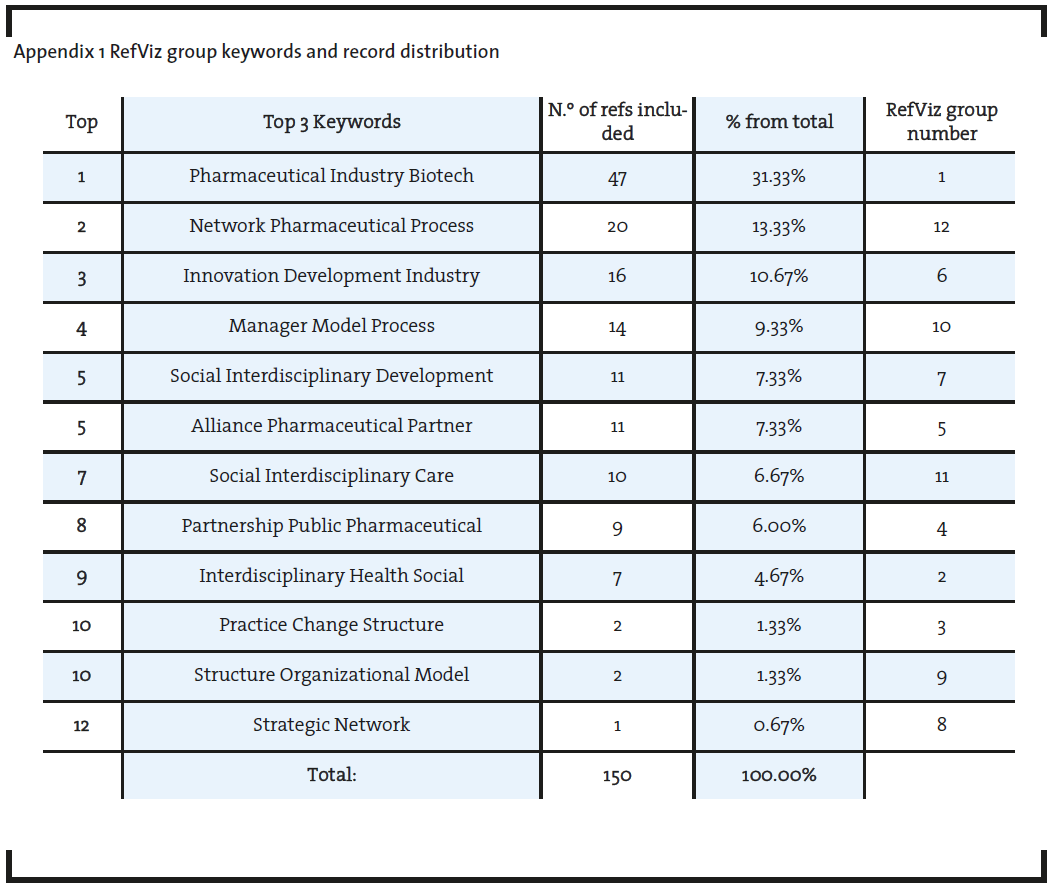

On October 26, 2007, we performed a systematic search on the topic of papers included in ISI Current Contents and Proquest, between 1998 and 2007. We limited our search to Social Sciences and used the following keywords: interdisciplinary multidisciplinary alliance* collaboration* partnership*.

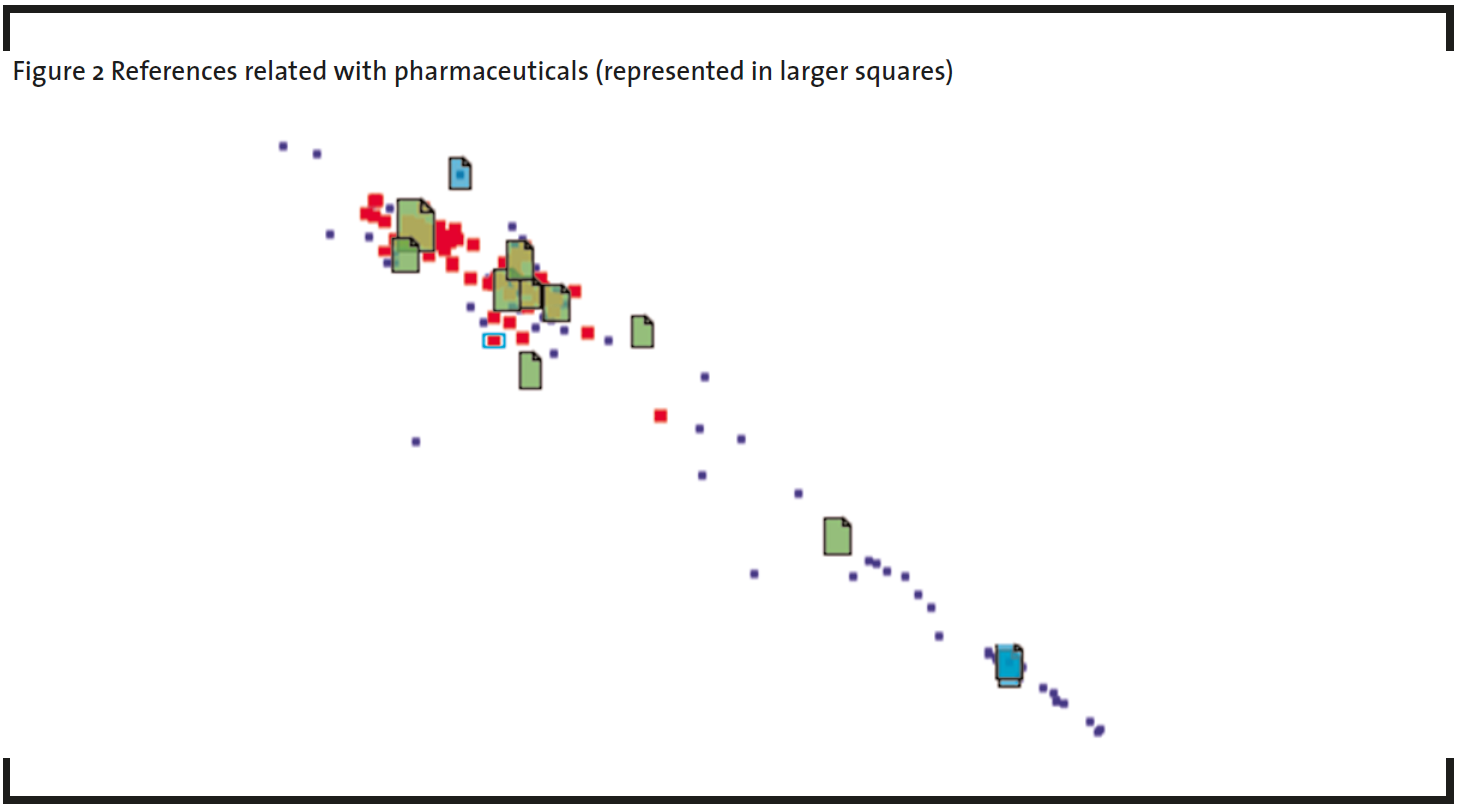

Our search yielded 153 results, out of which more than half referred to the pharmaceutical industry (see Figure 2). This allowed us to assume that, in the analyzed papers, the role of pharmaceutical multidisciplinary collaborations has been intensively studied. MDCs in the papers were linked with intense processes of learning, internal, external or mixed learning, and were based on internal capabilities, external networks and agents. We imported these 153 results into RefViz, and during these process, three papers were identified as outliers and removed from the sample. We were then left with 150 records. RefViz identified 12 main groups, as shown in Figure 1 and explained in Appendix 1.

Several of these groups referred specifically to the pharmaceutical industry and we performed a text search to identify all those records. Our search yielded 82 results, which are distributed among the 12 groups as indicated in Figure 2. These 82 results were subsequently analysed in depth using NVivo 7 software to identify key themes and concepts in a more reliable manner.

There was a strong suggestion that the pharmaceutical industry has frequently relied upon multidisciplinary partnerships, with internal and/or external organizations. For instance, Rothaermel (2001a, 2001b, 2002) refers to the preference for partnerships/alliances that leverage complementary assets in external collaborations, and a concern for appropriability regimes (de Leeuw, de Wolf and van den Bosch, 2003).

There is also a strong focus on external learning through partnerships and external knowledge sourcing (de Leeuw et al., 2003; Santos, 2003), raised by the specific characteristics of the pharmaceutical industry, i.e. low success rates, efficiency hurdles, large amount of information/knowledge sources to tackle).

Another interesting topic, mentioned by Mendez (2003) and previously addressed by Zeller (2002), brings out the importance of a project view in multidisciplinary collaborations, i.e. focusing on specific challenges and supporting coordination activities with “standardization of results and work procedures”. And as we have teams working on the projects, trust building and management of the optimal level of expectations (Adobor, 2005) emerge as important elements to help reducing the high percentage of alliances/ partnerships that fail due to non-technical reasons (Laroia and Krishnan, 2005).

Ultimately, multidisciplinary partnerships are presented in the analyzed papers as a way to enhance learning processes and knowledge sharing (Powell, 1998). Prior experience of collaboration or share of similar knowledge sources (Kim, Beldona and Contractor, 2007), as well as previous external relationships, are given high importance/are seen as critical to facilitate the absorption, share and dissemination of new knowledge created in multidisciplinary settings (Powell, 1998).

This would be a relevant factor to develop the absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990) of the firm, and also to develop network capabilities, i.e. capabilities linked to the firm’s ability to choose the right partners for the challenge at hand, to facilitate formation of new partnerships (Hagedoorn, Roijakkers, and Van Kranenburg, 2006; Roijakkers and Hagedoorn, 2006; Roijakkers, Hagedoorn, and van Kranenburg, 2005), as well as to coordinate resources, and manage relationships/partnerships.

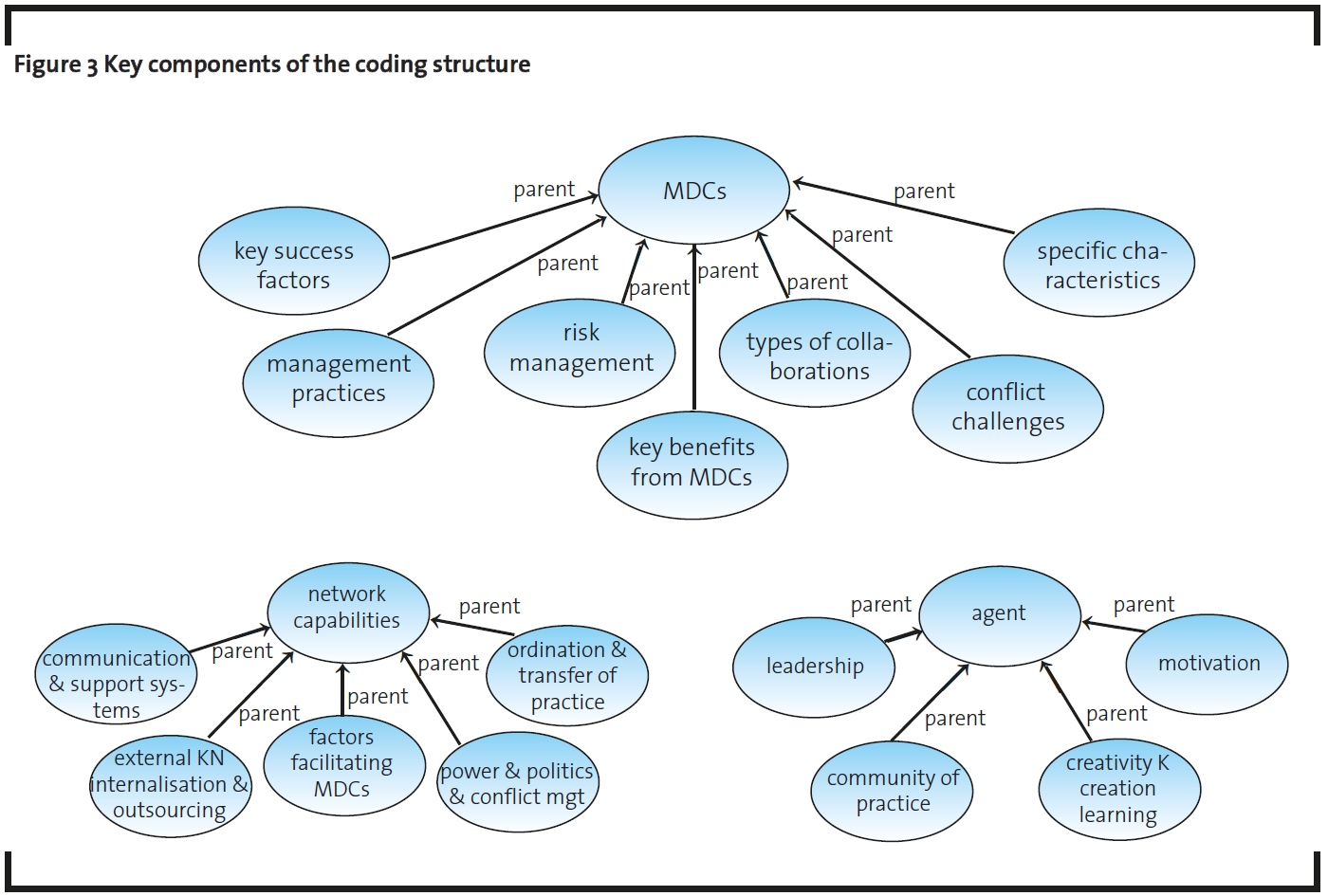

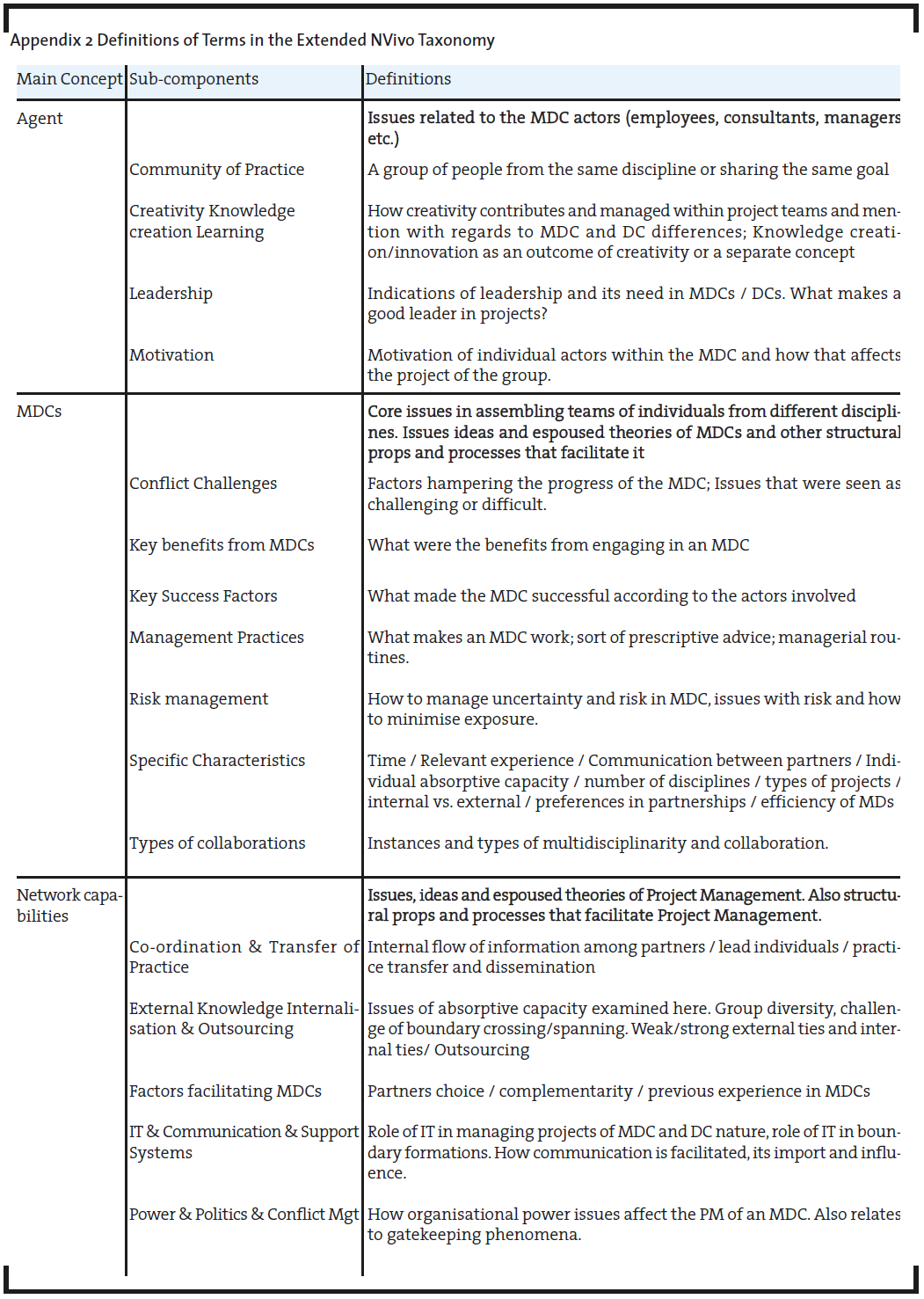

At the end of our analysis, the final analytical model derived contained three inter-related key topics: MDCs, Network Capabilities and Agent, as shown in detail in Figure 3.

These elements relate to the old issue of structure agency here reframed and subtly altered in the dialectics of network capabilities and the agent. The network is not structure alone but it also includes the dynamics of work to form the structure. Work is performed by the agents. We considered both components as well as the specific issue of MDCs. Definitions of the concepts for each major component of the taxonomy can be found in Appendix 2.

4 Insights from pharmaceutical industry: two case study comparison

The two case studies considered are in depth descriptive, holistic, and retrospective, aiming for theory building (De Vaus, 2001).

One case focuses on a global top-ten pharmaceutical multinational based in UK, and on the evolution of their bio-informatics group and the focus is on their projects related to the Human Genome Project (HGP), deemed vital for the new IS-based research paradigm that emerged in the industry since the mid-90s.

The other case focuses on an international firm located in a small-medium European economy, which produces, sells and does research in the pharmaceutical area and is part of the top-20 pharmaceutical firms in its national market, and on the multidisciplinary practices used in the drug development process.

The comparison is achieved by using the same analytical framework based on our eclectic understanding of the in-depth literature review performed in the first part of the empirical research. The main elements of the coding structure were presented in Figure 3. The data collected in the empirical study was analyzed in NVivo 7.0, using that analytical coding model.

4.1 PharmaCo case

In PharmaCo,12 interviews with 9 employees were performed between February 2005 and January 2006 and the case material covered the six years of the creation of a bioinformatics tool from 1999 to 2005. The specific project was designed to handle the information from the Human Genome Project (hereinafter HGP) and to provide the necessary bio-informatics tools to capture such data as they were generated.

Five of these interviewees were intimately involved with the project, including project managers and technical leaders (BI1-5). Three individuals were among the main stakeholders and clients of the bio-informatics group (SC1-3) while the remaining two participants were a high-level corporate information systems (CI1 and CI2) manager. The interviewees thus encompassed the three major communities involved in the project.

PharmaCo, the result of a major merger in the 1990s, responded early to the main challenges of the last decade posed by biotechnology and IT. They hired a number of people who were versed in IT and in science and together with pre-existing employees they formed a small group of bio-informaticians (BI) that was to handle the new technologies and data that were emerging. The newly formed multidisciplinary department managed a number of key external relations with novel organizational actors. Their products not only had to be proprietary IT, as there was no commercial software available, but also needed to be bio-science informed. The task of the BI group was formidable. This case study focuses on a major effort of the BI group to absorb the emerging HGP data.

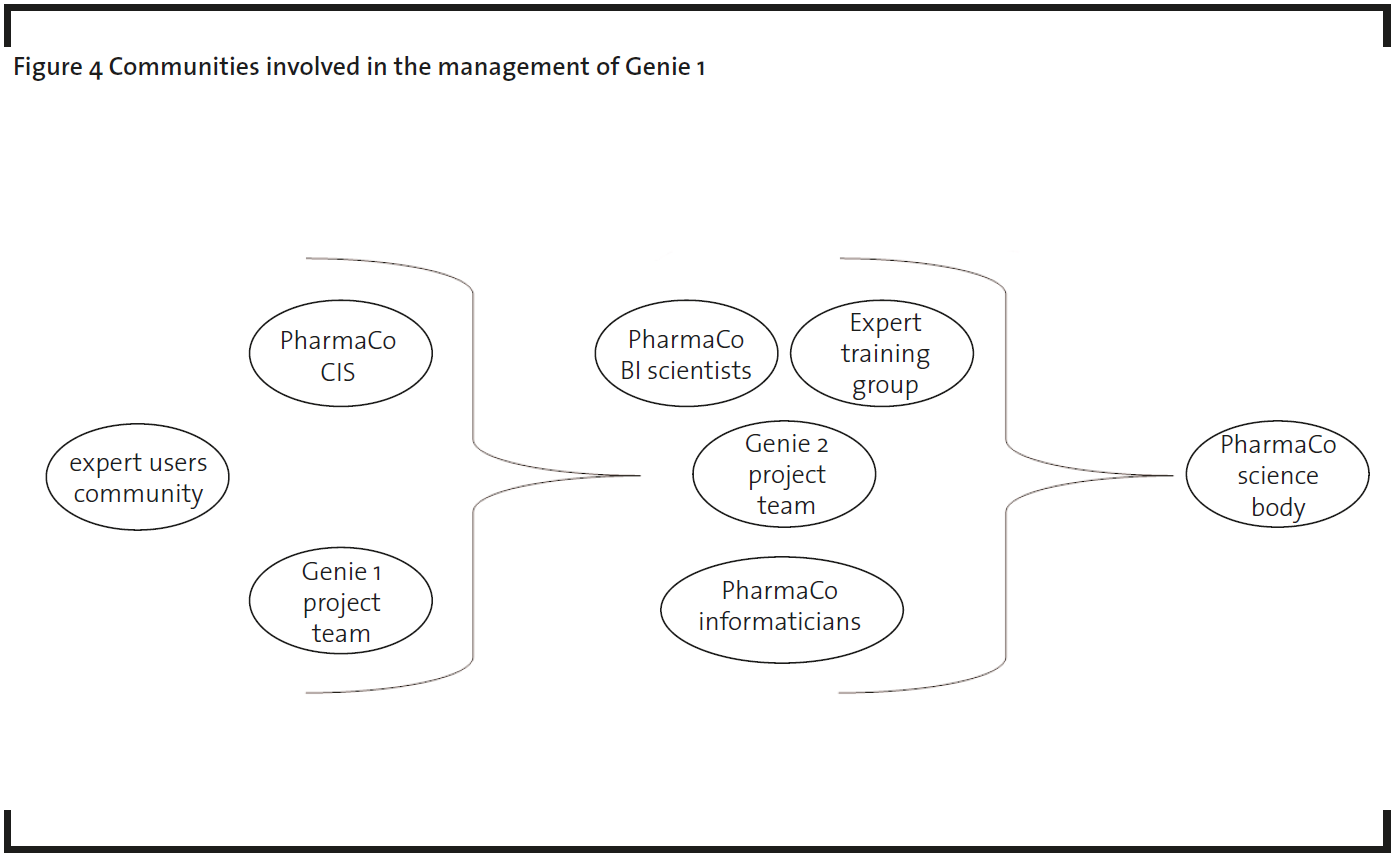

The BI group run two major projects for the HGP; Genie 1 and Genie 2. Both were multidisciplinary projects, involving a variety of actors. Genie 1 had four project members from different disciplines and sub-disciplines of bio-science and bio-informatics. It was based on a publicly available database called Genie which involved a public institute (PI) and its related open source group (OSG) that was supporting that PI’s goals. 2 years later Genie 1 was absorbed into Genie 2, a project that designed a proprietary tool to bring data from HGP to the internal scientific community. Genie 2 had a very elaborate stakeholder base and structure as illustrated in Fig. 4.

However it was quite a different multidisciplinary beast from Genie 1, with a more complex network of communities involved. According to its leader, from the beginning, Genie 2 was built to be a showcase of a bio-informatics project and aimed for achieving PharmaCo’s independence from the public software that Genie 1 was using.

It involved, from the design stage, expert users, scientists with informatics experience who resided within the PharmaCo research body, and the corporate IS. It also enrolled from the beginning the project team of Genie 1. By involving the various disciplines and communities from the beginning, Genie 2 managed a harmonization of goals and avoided many of the conflicts and risks that the Genie 1 team faced.

4.1.1 Agent

Over the period of six years there was a certain degree of stability among the communities of practice. The three main communities involved, persisted throughout that period and were perceived as quite well defined and distinct even though they collaborated within the same projects. For example SI1 claims:

“I feel we have missed opportunities to leverage the various cultures to our benefit. Within BI there is intrapreneurial spirit but also there is much conflict.”

The distinction between the three main communities is reciprocated by members of the other two communities. For example SC1 notes that:

“Research Area scientists are rampaging around finding technology and information. BI should get more involved, they should rampage around technologies, fast moving. It is difficult for BI. In Research projects a multiskilled team. In CI staff often gets de-skilled (software becomes obsolete etc…).”

Nevertheless when it came to project management the project work became a priority and the various communities were acting in a complementary manner adding to each other’s strengths. Explains SC2 with regards to Genie 2:

“It was particularly useful to work with the scientists for BI people. Genie team got surprised with how much we valued the literature part rather than the Bio-informatics part of Genie […]. It meant removing ambiguity even though we all knew that it meant sometimes that Genie could be wrong.”

Concerning leadership there were two types exhibited according to the participants. The first was the entrepreneurial, informal kind of leadership, which was the hallmark of Genie 1. In that project BI3 was the formal project manager but he explains with mild amusement that:

“BI1 would still go his own way. It did become his baby and he was personally convinced that it was the only way forward. Overall it was difficult to manage BI1. He would go on developing something and then come back in the sessions with his results. He found it hard to delegate and would not ask for help while BI3 spent much time persuading him to do exactly that. On the other hand BI1 has been very good at presentations. BI1 has been an unrecognized gem in that department”.

Thus, BI1 was informally the project manager of Genie 1 as he was the creative force behind it. In contrast, in Genie 2 the formal leadership was also representative of the actual situation in the project as the project manager was particularly keen to make GC an exemplar in project management and was hands on from the beginning.

“They did very well in getting the user requirements. (Genie 2 project manager) had a clear, strong vision.”

The creativity inherent in the BI group and the formal/informal leadership mix are both hallmarks of an innovative organization where new knowledge creation is paramount. In the case of PharmaCo there was a lot of creativity and learning present during the creation of the Genie tools. As BI1 observed of the science community during the development of Genie 1:

“They were interested in functionality data. Sometimes they would tell us something was completely wrong and we would feed that back to the Ensemble who then feed that back to the genome sequencing community. So they were using us as a filter for trying to improve the assembly or the annotation of the genome. They were telling us things they wanted to see and things they wanted to be able to do in the Ensemble. So we could also produce new functionality based on their feedback. So they were a big driver.”

Clearly Genie 1 was creating new knowledge as the scientists were intimately involved from the early start with the creation of the tool. Genie 2 incorporated them formally and explicitly in the structure of the project. It seemed however that each community of practice had a slightly different way of managing multidisciplinary projects. In Genie 1 there was also a lot of learning involved in engaging an external community such as the open source people:

“It produced a cultural change within informatics as well. It was so great and we did so many things to it, it had to drive us towards better practice. So it has led to programming practices which we didn’t have before.” (BI1)

4.1.2 Multidisciplinary collaborations

In the level of the project, we observed that the identification of the agents to the corresponding communities of practice can be the seed of much potential conflict. For example:

“The BI guys divide into targets leads etc., for us is more of a blur and we think in rather different terms.” (SC3)

“BI is not good at recognizing local developments and applying them globally. Cost-benefit analysis changes throughout the years. […] Scientists are not committed to anything other than developing drugs.” (SC1)

CI notes that there is even some antagonism between science and CIS:

“Within the science community, if you are not a scientist you don’t know. Definitely [there are] personality elements in this. Thus there is a lack of trust in Discovery.”

“The pharmaceutical industry has low recognition of the IS function, a fact that is represented by the line of report that we have. The pharma[ceutical people] have not mined the value of informatics and IS and have not utilized the information available.”

Bio-informatics has been by definition a multidisciplinary discipline and that was corroborated in the findings of this study. All five BI members had a mixed background of science and information systems. However, that often alienated them from both the CI and the science people. Yet within the projects the actualized benefits from the collaboration in creating Genie tools implementation cannot be overstated. Such benefits far outweighed the difficulties of communication:

“It was particularly useful to work with the SC for BI people. Genie team got surprised with how much we valued the literature search part rather than the bio-informatics part of Genie. We wanted Genie to provide Soft Bioinformatics. It scared them because it meant asking them to make decisions over science results. It also meant removing ambiguity even though we all knew that it meant sometimes that Genie could be wrong.” (SC 2)

“The resulting efficiency savings were enormous, for each ISB maybe 50% of their time was saved as GC now was doing automatically that part of their work.” (SC 2)

Such mutual understanding achieved through the MDC alleviated conflict and it was a key success factor in the Genie story. Such collaborations were based on informal relationships that would become formalized when the team would be forming. SC2 explains how the connection with BI group and the miniGenies he created led the BI group to seriously commit resources for Genie 2 as it was clear that Genie 1 was not covering the needs of the science community:

“I talked to (Genie Project manager) about mini-Genies, some time back. (Genie Project manager) and some other BI members saw a disconnect between the BI group and their user base. They were also embarrassed of mini-Genies, as it was built by people with limited technical knowledge (expert users within the science community) but it satisfied what they saw as the client base had many conflicts over there with issues of user involvement.”

Another key success factor was represented by the two artefacts and their continuous exposure to the various communities. The tools were instrumental in pivoting the evolution of the Genie project. In Genie 1, the continuous demonstration of its potential was actually crucial to keep the cohesiveness of the support coalition. Such engagement with the artefact seem necessary as Genie 1 involved a lot of dependency on public actors, something that BI and CI management in particular were not keen upon. The head of BI notes that:

“Ensemble was more a protective thing, to protect investment and time; there was much dissent from CI. However Ensembl gained external respect in pharma companies and the BI community for competence.”

Another important success factor was the commitment of actors in the Genie project. Each project had a champion who was there for the majority of the project’s running time and who cultivated a certain project mentality that persisted throughout macro-structural changes and team consistency changes. As BI 2 notes:

“A project develops its own culture. It is important and it works but the team should not lose sight of the customer. After awhile the project culture tends to take over and the goals, stakeholder committee aims etc. become engraved in stone/sacrosanct. However when the customer will say that what you deliver does not do for the business you can not say is the customer’s fault.”

In the case of Genie 1 the success was moderate as the customer was not as involved. However in Genie 2 the customer was actually part of the project team and made a tool that was relevant to the science base.

4.1.3 Network capabilities

We can already discern from the previous analyses that the network itself was rather important in the running of the multi-disciplinary project. For example we notice how the consideration of the underlying network shapes Genie 2. So in this section we will examine the network alluded to in the previous two sections and its interaction with project structure and the agent.

The issues of co-ordination and knowledge transfer are explicit throughout the interviewing process. Lack of co-ordination hinders knowledge transfer acknowledges CI 1:

“We spend 4 billion dollars on managing and changing the organization! The fragmentation of IS has a very high cost. The weakest IS area is that of information sharing and management. There are many reasons for that. First of all, IS is fragmented and there is a silo mentality. The default of information management was to be that information is available unless it needs to be protected while in reality information is not available unless it is given specifically to me. It is our own stupidity when we can not co-ordinate ourselves. It also gives leeway to innovation. There is a need for balance.”

That issue is not limited to IS. In BI there are similar difficulties:

“Science is embodied in real people. One of the downsides of a global organization is that anything new is difficult to diffuse across various sites.” (BI 4)

However for certain actors within the BI and the science communities such efforts in co-ordination were viewed as covert efforts of control:

“If process helps the work that has to be done is fine but if it becomes everything… The Matrix structure has broken it down, when you have to ask for permission seven people is much harder to achieve anything. Those little pockets of innovation need some lack of transparency at times. Not always a need for transparency.” (BI2)

The issue of control and politics appeared again and again during the interviews with the main focus on the ambivalent understanding of the bio-informatics function. That may have something to do with the culture of the group as explicated by a top level manager in the BI group:

“There is one simple trick I have been using. You tell people the trick, you explain how it works and still, people do not believe you. Basically, when somebody tells you to do something, you reply to them: «This does not apply to me and my team because what we are doing something different»…”

When it came to transfer of knowledge in this particular group the IT systems, the main artifacts of the BI group, were instrumental. Both in internalizing external knowledge as with the case of Genie 1, and in discoursing project parameters:

“Genie 2 was not from the beginning beautiful architecture. The focus was to get front end right and then work out the architecture. That was in contrast to the IS culture where the focus is first on the architecture and then the architecture becomes the constraint with regards to the front end usability and interface of the application.” (SC2)

Other tools facilitated internal knowledge transfer by improving upon communication means. Genie 2 team for example used WIKI and the intranet:

“WIKI was quite helpful. The Genie 2 team had provided access to all ISBs on the meeting notes and other information. The priority was on usability.” (SC2)

And both projects took advantage of training resources from the expert training group:

“Organizationally that’s where courses would be so that was all handed over to TAU. Same place for other courses such as the website, putting everything up on.” (BI1)

4.2 PharmaEU case

Between March and April 2008, we interviewed four employees of PharmaEU, located in key positions related to the R&D process, ranging from people in R&D department and in business development, or general management functions. We used as complementary information sources: internal documents (not confidential), public documents, archival records, researcher’s diary and site observation. We triangulated the opinions, using crosschecking between interviewees and post interview clarifications.

Our study centered on multidisciplinary teams in PharmaEU and network capabilities, with focus on both internal and external partnerships. We followed the coding structure derived from the literature review, presented in Figure 3 and Appendix 2, to construct our personalized interview scripts. We uncover issues related to: internal multidisciplinary teams for R&D, both formal and informal, partnerships with external agents, outsourced or licensees.

We next present key insights from the data collection and analysis, following the key components of the before-mentioned coding structure.

4.2.1 Agent

The “communities of practice” in PharmaEU, as indicated by all interviewees, are well defined and functionally represented. All people participating into R&D tasks have their responsibility quite perfunctorily defined, especially if we are speaking of multidisciplinary collaboration for R&D. Note that there is a concern for complementarity when a multidisciplinary team is created:

“The idea is that all these people come to the meeting to represent their own functions”

“We have to have complementarity and less redundancy […], we need to have a wide pool of competencies and opinions.”

In terms of creativity and learning, several issues are worth of mentioning.

First, we got a grasp of some of the pharmaceutical industry serendipity linked to a very systematically defined R&D process, which can be useful, nonetheless:

“There are things that need not inventing, fortunately there is nothing here to discover. People know what they are doing, they know the steps they need to make. Of course, there is a creative aspect that is not in the books, and we need to have people to have ideas for new products.”

Then, we see the advantages in terms of creativity and better decision-making associated to a multidisciplinary team:

“The very concept of discussion is associated to evolution. When we are discussing something, this is due to different opinions and several possibilities emerge: either we have an opinion clearly better than the other, and we’ve won already, either is it not obvious and maybe the combination of two or several ends up as a major advantage for the next step. From this perspective, the discussion is fundamental.“

At last, there is a learning experience associated to the duration of a multidisciplinary team, both in terms of knowledge creation for R&D:

“Because many people have been involved since the beginning, we have been part of a learning experience.” and in terms of relating with one another:

“Entropy reduces as we work together, no doubt about it, our experience shows it. In the beginning, there was more entropy in terms of e.g. information fluidness and of how we talked to each other. There were issues to clarify and as time passed, the entropy has been reducing.”

Leadership seems a multifaceted issue, and is perceived differently according to the type of internal multidisciplinary team. When speaking of informal, ad-hoc teams, created so as to respond to specific, usually technical issues, leadership is not perceived as an individual, but more with a coordinating role, with one coordinator in each function present in the team.

When speaking of formal teams, in our case one specific team created so as to coordinate and align objectives and actions between the various functions involved in the R&D projects, opinions on leadership are divided.

Part of the interviewees indicated the official coordinator of the team, in charge with the agenda and meeting logistics, to be the leader. His role is mainly ensuring that all “voices” are heard and that participants speak openly:

“My role is to facilitate the meeting, to do the agenda, to run the meeting essentially […]. I am in charge of the logistics and make sure everything happens…that minutes go out and that people are done what they are supposed to do.”

Part of the interviewees referred another member of the team as the leader, mostly in an informal sort of way. Regarding the leadership role, opinions diverge.

In terms of external partnerships, leadership belongs to the Sponsor, and there is coordination between Project Managers on both sides, which then create the necessary linkages inside their own organizations.

4.2.2 Multidisciplinary collaborations

Multidisciplinary teams were perceived as having several insightful characteristics, presented next.

The diversity of expertise brought up by multidisciplinary experiences is seen as a very positive element.

“In the company, we end up having several competencies that we can have around the same table, specialists in various areas that complement each other in the interpretation of the information we receive.”

“We make a phone conference and on one side, we have specialists from the various area, whilst on the other side we also have these specialists, and instead of Project Managers speaking with one another, we can have a more technical discussion between the various specialists.”

Task and responsibility definition is perfunctory, as mentioned before, based on functional expertise, on “silos of skills”.

“An R&D project involves different areas, and due to that, for key tasks in the R&D process, there is a direct or indirect linkage to specific teams. It is not difficult to know which are the teams holding responsibility in that area.”

Communication between the members of the multidisciplinary teams, and in partnerships with external actors, was a widely discussed topic, frequently mentioned by interviewees.

In internal teams, communication is fluid, using both formal and informal circuits, yet following hierarchical flows, clearly defined, if a formal decision-making is involved.

“Formally, when the communication is not defined, the rule I use for me and my team is common sense, is that in case of doubt, we use the hierarchy.”

With external partners, communication is technical, and ruled by confidentiality agreements before any type of sensitive information being exchanged.

“Before any type of information is exchanged, we put in place a specific confidentiality agreement. This is necessary not only for us, but also for them, because they also give us information which is confidential from their point of view.”

“As far as I know, there has been no leakage of confidential information. No breach of rights or copying. We only work with top companies, they are credible. It’s like a loyal, they cannot reveal data, they work based on a clear policy of information control.”

In terms of instruments supporting communication, either internal or external, there is generalized use of phone, phone conferences and email, which complement face-to-face encounters. Phone is used in case of doubt, to clarify issues.

“Today, people tend to believe that e-mail solves everything. It doesn’t. Normally, when the situation requires it, we have a face-to-face meeting. […] Sometimes we do phone conferences […] and like that the information shared by e-mail was contextualized, there is less chance to be misinterpreted.”

There is a common concern to minute the key decisions of any verbal meeting, and result is sent by e-mail to all participants.

“Every time we have a meeting, call conference, whatever, we try to put everything down in written, in minutes, so as to be able to consolidate there what we have decided… .”

“…communication is not difficult, but has to be very vigilant, exactly because we want to work in the same context, do the things we want to do in the way we want it to be done, and because the information needs to be shared the way we want it to be shared.”

And multidisciplinary teams are seen as an open communication channel:

“It seems to me they create discussion channels so open that they ease not only the information flows, but also sharing specific issues regarding possible changes in plan, future development paths etc.”

In terms of other positive aspects associated by interviewees to multidisciplinary team experience, we mention:

“Coordination, sharing, communicating

knowledge, being aware of where we are, planning…”

“Opens our horizons, disseminates information and allows receiving more information…”

“Allows having a more aligned decisionmaking process…”

As of the success factors and management practices, we mention:

- small team dimension and unchanging team composition

“It helps being quite small […]. We’re able to communicate easily with each other, there are no twenty decision layers. We’ve got the same people, we formed a relationship in many years […]. We have deep understanding of where we are.”

- knowing your external partner, and monitoring closely project evolution

“You need to know, to see, who the clients of that partner are, with whom they work, where they are, what their philosophy is!”

- knowing how to deal with entropic communication, that cannot be dissociated from multidisciplinary experiences

“Either somebody says: ok, let us start again and explain the context so that we can all understand where we are, or the specialist says: hey guys, believe me, I am the expert! Not as an imposition, but as a way to move forward…”

However, the multidisciplinary teams are not seen as efficient experiences:

“I think efficiency could be better for all of us…”

“That team is basically inefficient!”

“I would say results are more positive than if we wouldn’t have the team…”

They are also situations (both internally and externally) where conflict exists, more in the sense of misunderstanding and disagreement.

“The conflict is not verbalized, is part of our culture…, yet sometimes things can only advance if there is conflict.”

“There are always conflicts. Big conflicts, I wouldn’t say. Basically minor. […] but we have to resolve all of these things.”

Several challenges were mentioned:

- growing organization hurdles: structure needs to be reorganized, and teams and relationships will evolve;

- communication difficulties when dealing with hierarchically superior figures in multidisciplinary teams;

- being too smaller team, which leads to compromises;

- being politically correct all the time when project is seen as going on the bad path.

Another complex issue is drawing the line and choosing between performing one task internally or doing it with external partners, in multidisciplinary and interorganizational collaborations.

“It’s complicated. We have this philosophy of wanting to maintain the maximum of issues under our direct control. It doesn’t mean we have no control over the outsourced partner, but it’s not direct.” Several factors motivate the choice of performing tasks internally, prioritarily:

“First, because we create and maintain our know-how. Second, because we end up maintaining the project, which is confidential by default, even more confidential. Third, because we end up having a tighter control over the project.”

When there is the possibility to do something with external partners, there is a duly analysis of its reasons:

“Insufficient know-how, capacity, or time! And we evaluate these reasons to see if there is a reasonable advantage performing that task outside the company. The decision balances in-between giving up the 100% control we have now, and trying to create internally the conditions, in a short timeframe, to do the task. And then, these conditions can serve other projects.”

The logic is:

“When we can do it in-house, we do it. When we have to outsource it, and if we can outsource only partially, we do it. Why? Maintaining know-how internally, creating conditions for future projects, and fundamentally controlling the project.”

And ultimately, disadvantages were pointed by interviewees.

“I cannot see any disadvantage except for the fact that in order to work within such a team, people have to know everything in their functions and think globally of the project as an entirety. If people are not able to come at the meeting and to think about the effect on other people’s functions, then it does not work. People have to be able to think outside their day-to-day stuff.”

“It can get a bit entropic! […] As one does not understand a specific question related to our field, maybe because there is a certain technical distance between the different areas, you can get highly entropic discussions. And never ending storied where one says A and the other understands B and they keep on and you don’t get out of that.”

“In complementary areas, people may think: well, if I am doing this, they probably do that! And if they do not talk and just assume, we can have serious surprises!“

4.2.3 Network capabilities

Conflict management is something present in all interviewees’ discourse, casted though under a positive light.

“We have disagreements, but generally we have to find a solution and a way forward.”

Coordination is a key issue, well debated between the informants. A multidisciplinary team is seen, by itself, as a coordination mechanism.

“We opted to create a transversal, multifaceted organization not so much to facilitate information flows, because this is easy, but to allow discussion of products and problems, to discuss why things are changes and why that was done.“

Coordination is also seen as different, according to the partners involved:

“Interaction depends on who we collaborate with and with the nature of the issue we’re dealing with. Some areas are highly complex, because we’re speaking of long-term interactions and millionaire contracts. […] In some cases we’re in a top position, in others, in a low one and we need to adapt to the rules.”

Coordination is performed applying good project management techniques and close monitoring of task execution and quality. Is never seen as easy.

“It’s manageable. Sometimes, it can get quite hectic.”

“It’s not difficult, but it’s not easy. Because there are ways of working which are different from our own. And when we have an external partner involved, we also need to coordinate the internal linkages! […] Know-how is distributed and we need to integrate it! […] Sometimes we need to manage everything: the project and the environment, so as to see and help things getting on the track when that happens.”

Information technologies more widely used in other companies, e.g. Intranet, discussion forums, instant messaging, are not used in PharmaEU. Internally, teams function with shared drives, regulated by access permissions, and outside, information is shared via email or, in more sensitive alliances, in specific highly protected data-sharing facilities.

“I don’t miss IT tools from big companies, not really, because at the end of the day you need to have a personal interaction with people, it’s always the best way. We’re lucky, One of our strengths is we are small […] if we need to talk, we stand up and walk there.“

The very usage of multidisciplinary approaches to analyze and tackle information helps internalizing knowledge coming from outside the company or outside the functional/disciplinary area.

“Report drafts are reviewed by many people of different expertise, so as we can reduce the inherent risk of not knowing everything. We need to be multidisciplinary and precautious.“

“In the company we have different competencies, different specialists that we can put at a round table and they can complement each other in interpreting the information we receive.”

Yet, there is a draw of attention on language misinterpretation:

“One might think, hey this is easy, it’s all international. That’s wrong. The fact that we need to use in our contacts with the exterior a language which is not ours, is complex. We are fluent in English, we have to be, but sometimes the way things are said or written may lead to misinterpretation.”

The internal transfer of knowledge or information is done hierarchically, punctually using the shared drive, using a careful information management approach.

“All the team working within that project receives all the information. The others do not because the information management says that, for a reason of efficiency, when I am reading something I do not need, I am wasting time.”

“The information is essential to that person for two reasons: because I need feedback or because is essential for his/her work to continue. If this is not the case, the person does not receive the information. […] and then we have the regular meetings to share other issues within the team.” Ultimately in this topic, interviewees referred linkages with external partners, service providers, to be slightly different in terms of coordination and management.

“Outsourcing means you will have to deal with delays, some budget variations, and with all those small things you cannot control […] There are various ways we can deal with this: the more control over the projects, the better…we do it by doing audits, meetings, minutes and results (i.e. reports, timelines, and budget).“

5 Discussion

5.1 Comparative sum-up of the two case studies

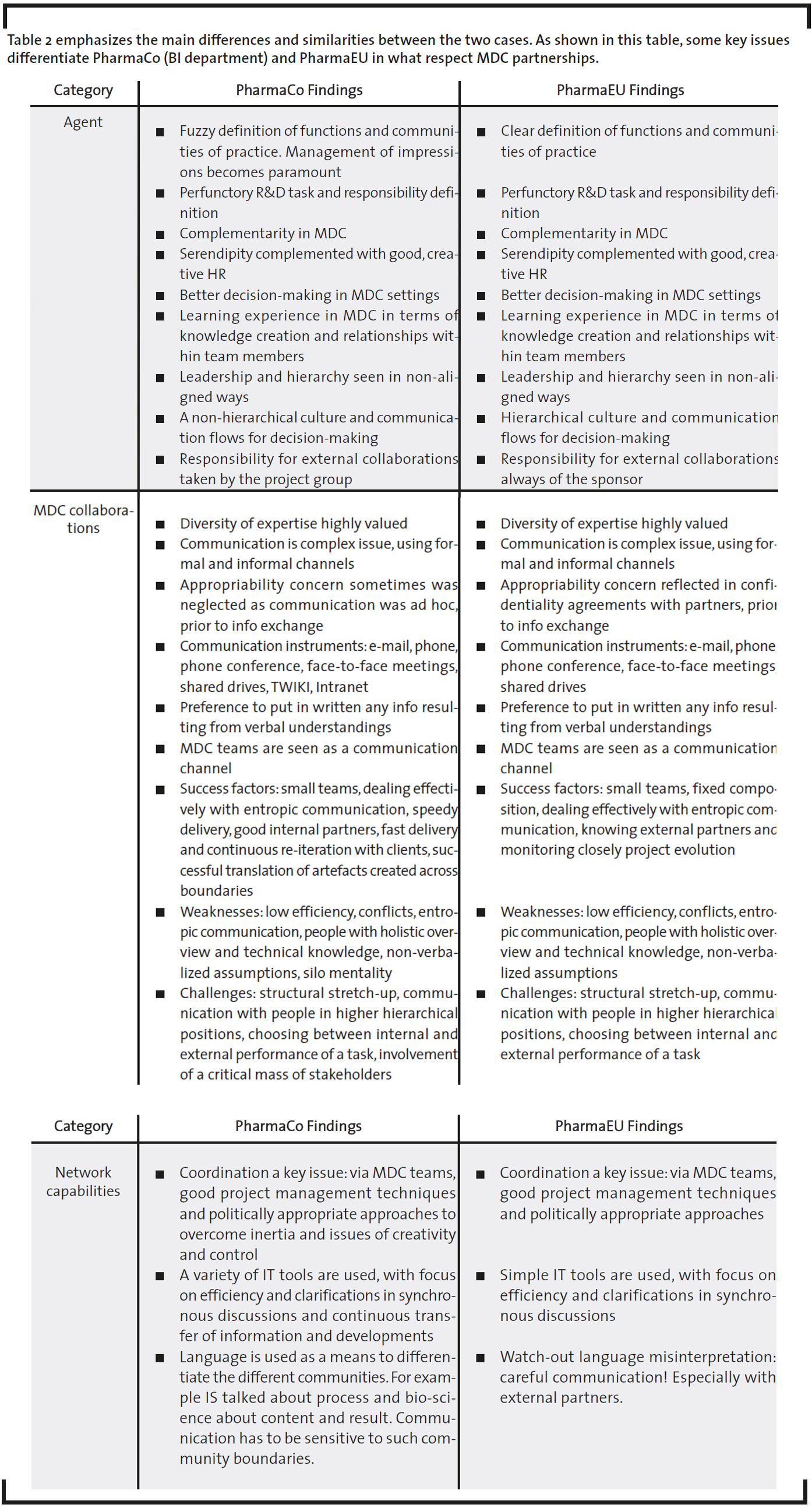

Table 2 emphasizes the main differences and similarities between the two cases. As shown in this table, some key issues differentiate PharmaCo (BI department) and PharmaEU in what respect MDC partnerships.

A first key difference is a different focus on exploration/exploitation in pharmaceutical R&D.

In PharmaCo, analyzed projects are exploratory in nature, more aligned and focused on radical innovation, yet there has been an evolution towards more exploitation approaches. In PharmaEU, focus is essentially on exploitation, on more incremental approach in R&D, focused on me-too chemical drug development. This difference has effects onto learning, and increased coordination and control reflect in the focus on practices instead of content.

Another difference is paramount in organizational cultures and hierarchical structures in the two cases. If PharmaEU is hierarchical and vertical, with clear role definition, and strict information management policy, PharmaCo shows some vagueness and fuzziness at this level, a more horizontal and flexible hierarchy, focused on projects, which creates specific management challenges, e.g. management of impressions.

Surprisingly to some extent, the two cases are not as different as we might have thought at the beginning.

We were comparing the department of a Big Pharma (i.e. multinational with a good presence in top twenty companies worldwide and reasonable part of world market share), multidisciplinary by nature, yet still only one function, with a medium-sized pharmaceutical firm, international, with recent drug development activities.

Furthermore we examined a department specializing in the discovery side of pharmaceutical R&D, traditionally the most creative department of the company, full of maverick scientists and new exciting technologies with the whole R&D function of a European midsized company.

The dramatic differences in the context of our two case studies make the points of conjunction even more important.

5.2 Limitations

One limitation is related to the research method. Our research was based on two case studies. Notwithstanding the methodological care, case studies have their inherent limitations, and only allow abstract generalization, i.e. to the theory (Yin, 2003). Whilst the findings can be used as inspiration for managers to identify hurdles or best practices and develop specific solutions for their own situation, the researchers cannot state that the findings will most probably apply in a specific situation.

The other limitation is related to the data collection. In spite of using a research protocol to orientate data collection and analysis, and maintaining close contact during all that phase, which increases internal validity (Kofinas & Saur-Amaral, 2008; Yin, 2003), interviews and secondary sources were collected by two different researchers (i.e. the two authors), in different geographical and language contexts and distinct companies. Due to confidentiality concerns, there was no possibility to cross-check the way data was coded by the other researcher, and subjective interpretation might affect the quality of our findings due to different Weltanschauungen.

The implications for theory and practice that hereby follow should be seen in the light of the before-mentioned limitations.

5.3 Implications for theory and practice

5.3.1 Agent

Communities of practice were proven not only important and present as the theory pointed out (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Roper and Brookes,1999; SaurAmaral, 2005), but very clearly defined, which is a novel insight.

On one hand, they were stable and cooperating in most cases, however they needed to function in a context where roles and responsibilities were perfunctorily defined, and this may be important for project leaders or facilitators as role diffusion or redundancy may prove to be a barrier to goal achievement and may increase conflict and communication entropy.

But on the other hand, empirical data in PhamaCo pointed out that the stability among those communities might limit learning and spillovers from MDC learning to the functions involved, which was not coined in the literature (e.g. Nissani,1999; Romm,1997; Saur-Amaral, 2005, 2009). However, in PharmaEU this aspect was less relevant, as the creation of good communication channels was a priority to diffuse knowledge among functions, using essentially the organizational hierarchical.

This may signify that the efficacy of communities of practice depends upon the specific context and communication channels, and the creation of a cumulative organizational learning experience based on team learning depends on culture and management practices. The well developed theory on organizational learning and learning organizations (knowledge management and strategic management scientific fields) (see Burgoyne, Pedler and Boydell, 2009; Dierkes, Antal, Child and Nonaka, 2003; Dodgson, 1993; Garvin, Edmondson and Gino, 2008; King, 2009; Senge, 1993; Senge, 2000; Skerlavaj, Stemberger, Skrinjar and Dimovski, 2007; Vera, 2009; Vera and Crossan, 2004, among others) will provide more insight into these areas and it should be used as starting point for further studies or for the development of good management practices.

When speaking of creativity, knowledge creation and learning, theory emphasized that MDCs were linked to intense learning, internal, external or mixed (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Powell, 1998; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005), while the empirical study complemented this scientific knowledge with insights on the differences existing between the various communities of practice, importance of an innovative organization to stimulate communication and knowledge share, as well as the positive effect of stability of team members onto the reduction of communication entropy.

This has a direct implication for management, as it is common practice in pharmaceutical industry to change multidisciplinary team members along a project (Attridge, 2007; Atun and Sheridan, 2007; Saur-Amaral, 2009), which goes against our findings, where it is seen as a factor to increase entropy. And also points that there is little sense to make an effort to create a creative multidisciplinary team if members come from organizations which are not endowed with innovative cultures.

Note though that this intense learning process was not pain free. Whilst some of the participants in MDCs would appreciate the learning that came from a discussion and debate, which was seen as a way to evolve, others would complain about entropy, low efficacy and somehow arrogant attitudes of other participants. Conflict, as mentioned later in this section, is emergent, as theory also predicted (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Saur-Amaral, 2005) and managers should be sensitive to this aspect and look to coordinate and focus people on the project’s success, a good practice pointed by our findings and predicted also by some authors (Mendez, 2003; Zeller, 2002).

Another aspect related to learning and creativity: external MDCs are led in different way, at least in one of the companies we studied. There is more technical and procedural learning and communication is well-defined and controlled. This may signify that internal and external MDCs should be studied separately, as they have different characteristics, and also that they should be managed differently. Current studies (e.g. Attridge, 2007; Atun & Sheridan, 2007; Kofinas and Saur-Amaral, 2008; Saur-Amaral and Borges Gouveia, 2007) did not make this separation, and this is a novel insight in the field.

Theory indicated that leadership was important for MDCs (Adobor, 2005; e.g. Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005). Our empirical study showed that informal and formal leadership work effectively and complement each other in such collaborations, and also that there must be somebody to ensure that everybody is heard, when relevant, and that the presence of hierarchical superiors in multidisciplinary teams may prove ineffective, as it limits creativity, free communication and knowledge share. Managers should thus avoid putting in the same project team people from various hierarchical levels.

Our findings also suggest that in MDCs, two types of leaders/managers should co-exist, being formally appointed or not: the inspirational leader and the project manager. Each one has different roles. The inspirational leader motivates and makes participants believe in the project, being the “creative thinker/visionary” character; he/she stimulates discussion and creativity and ensures commitment is high. The project manager makes sure coordination is done, and that the project is going in the right direction, having a more to the earth approach. Both future studies and managers should take into account this aspect.

5.3.2 MDCs

Some conflict and challenges were associated in the literature to MDCs (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Laroia and Krishnan, 2005; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Saur-Amaral, 2005). In addition, our empirical study registered differences in formulating problems that created confusion and difficulties, antagonism and differences in the way communication flew between members. Also, the creation of efficient communication channels was seen as a good practice to reduce the impact of this aspect.

As a good practice to overcome challenges and conflicts, managers may want to discuss, confront, and monitor task execution instead of assuming that the other communities and team members will do anything. As communication is entropic and imperfect, assumptions are highly counterproductive. Using the project as a motivational tool can be useful, as this was a good practice identified in our findings which could help overcoming difficulties.

In contrast to what literature had suggested (Nissani, 1999; Romm, 1997; Saur-Amaral, 2005; Saur, 2005), MDCs were seen as a way to obtain efficiency and time savings at project levels and to remove ambiguity.

In both cases, internal MDCs were matrix structures on top of a vertical hierarchical structure, they were seen as an open communication channel. Thus, future studies should validate again the efficiency issue and better contextualize it.

Managers should continue to promote such initiatives if only for allowing communication to flow between the various communities represented in the organization, but also regulating the type of information that flows, in order to avoid conflicts and misunderstandings due to conceptual confusions.

Our empirical study pointed out some new key success factors for MDCs:

- mutual understanding;

- informal relationships;

- commitment of actors to project;

- presence of a champion in each project;

- good coordination mechanisms, as long as not seen as control;

- clear task and responsibility definition;

- small team dimension;

- good communication channels, mediated by technology or not;

- stable team composition.

These success factors should be validated in future studies and managers should inspire to create conditions for these elements to be present in multidisciplinary projects. Good practices may also serve to better draw network capabilities.

5.3.3 Network capabilities

Regarding coordination and transfer of practice, an issue raised in the literature as a key way to share and disseminate knowledge in MDCs (Caruso and Rhoten, 2001; Chiesa and Toletti, 2004; Nissani, 1999; Pellmar and Eisenberg, 2000; Romm, 1997; Roper and Brookes, 1999), we had the confirmation that the presence of the right coordination may facilitate MDCs and its absence may hinder it.

In large organizations like PharmaCo, structural barriers may hinder communication and coordination, and information technologies can play an important role as a platform to share and disseminate knowledge.

In medium-sized organizations like PharmaEU, coordination may be seen as a key issue, and good project management techniques and close monitoring of task execution and quality may be seen as fundamental for project success.

When internal knowledge transfer is hierarchical (formal), informal contacts interfere and allow knowledge share. Managers should not let aside the coordination and good project management techniques even when stimulating the team to cooperate and share knowledge. Entropy, lack of clear goal-setting and difficult communication may have a direct negative effect on goal achievement.

Regarding external knowledge internalization and outsourcing, our empirical study only confirmed that there was a concern for group diversity in internal settings or in situations where light must be shed over external knowledge, however in external MDCs it depended on the on motivation of partnership: lack of knowledge or lack of capacity.

In the first case, there is a concern for complementarity and diversity, as the literature suggested (de Leeuw, et al., 2003; Santos, 2003), in the second one, only for efficiency and given proofs.

There was no specific reference to the experience effect which enhanced network capabilities, as literature predicted (Hagedoorn et al., 2006; Powell, 1998; Roijakkers and Hagedoorn, 2006; Roijakkers et al., 2005), but there was reference to the fact that choice between internal and external partnerships was far from easy, in spite of the usage of MDC approaches could help understanding and internalizing knowledge.

Contact with external partners was seen to involve different types of coordination, as politics and control were working in a different way than they did internally.

A final note on knowledge transfer and the role of information technologies, pointed by the literature as facilitators (Arora, Gambardella, Hall and Rosenberg, 2010; Bailey and Zanders, 2008; Barnes, et al., 2009; Gassmann, Reepmeyer and von Zedtwitz, 2008; Hohman, et al., 2009; Hughes and Wareham, 2010; Williams, 2008).

Our empirical study showed that technologies can facilitate (PharmaCo), but communication it can work just as nicely without it (PharmaEU). This would lead to the possible conclusion that in smaller organizational settings, communication is better done with few technologies, whilst in bigger organizational settings is seen as a necessary tool to allow communication. So it may all depend on the context and dimension of the organization.

Knowledge transfer resulting from MDC needs to occur, independently of the technological or not technological tool that makes it possible, so it will depend on the efficacy of current communication channels.

Future studies should probably best focus on the efficacy of those channels instead of information technologies, which represent more a mean than an end per si. Managers should also think twice before implementing information technologies to improve communication, as more often than not in certain types of organizations it works the other way around.

6 Final considerations

The two cases uncovered two different stories, providing relevant information for managers working in pharmaceutical industry or other practitioners linked to drug development, so as to better understand its dynamic, Multidisciplinary partnerships were widely present in these cases. They appeared to be part of the industry way of thinking and best practices to deal with complexity, which made them a good object of study to understand the way they work and delineate strategies for other industries where they are less frequent.

This research aimed to answer three questions, which we satisfactorily have addressed, based on theoretical review complemented with strong empirical base. We managed to draw more light over MDC partnerships in pharmaceutical industry. We indicated that MDC collaborations are useful in both internal and external settings, as long as applied to the right challenges. We also indicated some challenges and benefits from MDC collaborations, as well as some good practice.

The two cases gave surprisingly similar results despite the different business context, the main differences centered around networks, arising from the exploration-exploitation focus and different organizational cultures. We might thus conclude that activity’s nature changes the network and affects agents’ behavior. Our findings allowed seeing how differences in some categories of our coding taxonomies may affect agent behavior.

We could also see that there was a confirmation of standardization of results and work procedures in pharmaceutical companies working in chemical R&D, complemented with the importance of creativity either by good human resources, or by more flexible, horizontal culture. This might signify that in pharmaceutical firms, at least in those somewhat linked to chemical R&D and blockbuster/me-too strategies, there is a high probability to find similar behavior regarding, at least, MDC partnerships and network capabilities. It might have been a coincidence that two cases so different were so similar, yet this finding is a strong indicator that MDC issues may apply to other similar companies, too, acting in the pharmaceutical industry.

Complementarity concern in MDC partnerships, both internal and external (aspect not reflected in our literature review), was present and was considered good practice. Standardization of results and work procedures was confirmed, but complemented with the importance of creativity (in people or organizational structures) to overcome reliance on serendipity.

Redundancy was not seen as a useful tool to promote creativity. Our findings further highlighted the importance of careful choice of partners and functions, both in internal and external collaborations to minimize knowledge duplication and to maximize learning.

Prior experience of collaboration was seen as positive, in the sense it helped overcoming communication hurdles, yet a point is essential: in external partnerships, this should not reflect in easing the monitoring of the process and intermediate results, as effects were perceived as negative on project success.

We also saw that innovation management in pharmaceutical industry is reliant on multidisciplinary organizational arrangements. Attention to complementary network- and agent-related issues seems vital for the success of the innovative enterprise, in pharmaceutical industry or outside it.

Good managerial practices for multi-disciplinary practice are complex and nuanced and rely on flexible, adaptive and contextual processes and managerial understandings. Therefore, further studies should take into account this personalized culture context so as to understand better the respective practices and further their validity in different settings.

7 Acknowledgements

Authors kindly thank management and interviewees from the two pharmaceutical firms for their availability and collaboration during empirical research. We also acknowledge the comments of conference participants at R&D Management Conference 2008, which took place in Ottawa, Canada, and JBC’s Executive Editor, David Grosse Kathoefer, and two anonymous reviewers. Without their relevant opinions, critics and suggestions, our paper would not have reached this level of scientific communication.

References

Adobor, H. (2005). Trust as sensemaking: the microdynamics of trust in interfirm alliances. Journal of Business Research, 58(3), pp. 330-337.

Arora, A., Gambardella, A., Hall, B., and Rosenberg, N. (2010). The market for technology. Handbook of Economics of Innovation—Hall BH, Rosenberg N, eds.

Attridge, J. (2007). Innovation Models in the Biopharmaceutical Sector. International Journal of Innovation Management, 11(2), pp. 215-243.

Atun, R. A., and Sheridan, D. (2007). Innovation in Health Care: The Engine of Technological Advances. International Journal of Innovation Management, 11(2), v-x.

Bailey, D., and Zanders, E. (2008). Drug discovery in the era of Facebook–new tools for scientific networking. Drug discovery today, 13(19-20), pp. 863-868.

Barnes, M., Harland, L., Foord, S., Hall, M., Dix, I., Thomas, S., (2009). Lowering industry firewalls: pre-competitive informatics initiatives in drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 8(9), pp. 701-708.

Bruce, A., Lyall, C., Tait, J., and Williams, R. (2004). Interdisciplinary integration in Europe: the case of the Fifth Framework programme. Futures, 36(4), 457.

Burgoyne, J., Pedler, M., and Boydell, T. (2009). Towards the learning company: concepts and practices: National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER).

Caruso, D. and Rhoten, D. (2001). Lead, follow, get out of the way: sidestepping the barriers to effective practice of interdisciplinarity: Hybrid Vigor Institute.

Chiesa, V. and Toletti, G. (2004). Network of Collaborations for Innovation: The Case of Biotechnology. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 16(1), pp. 73-96.

Cohen,W. M. and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37(1), pp. 128-152.

de Leeuw, B. J., de Wolf, P. and van den Bosch, F. A. J. (2003). The changing role of technology suppliers in the pharmaceutical industry: the case of drug delivery companies. International Journal of Technology Management, 25(3-4), pp. 350-362.

De Vaus, D. A. (2001). Research design in social research. London: SAGE.

Dierkes, M., Antal, A., Child, J., and Nonaka, I. (2003). Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge: Oxford University Press, USA.

Dodgson, M. (1993). Organizational learning: a review of some literatures. Organization studies, 14(3), 375.

Garvin, D., Edmondson, A. and Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harvard Business Review, 86(3), 109.

Gassmann, O., Reepmeyer,G. and von Zedtwitz, M. (2008). Leading pharmaceutical innovation: trends and drivers for growth in the pharmaceutical industry: Springer Verlag.

Gomm, R., Hammersley, M. and Foster, P. (2004a). Case Study and Generalization. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley and P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method: key issues, key texts. London Sage Publications.

Gomm, R., Hammersley, M. and Foster, P. (2004b). Case Study and Theory. In R. Gomm, M. Hammersley & P. Foster (Eds.), Case study method: key issues, key texts. London Sage Publications.

Hagedoorn, J., Roijakkers, N. and Van Kranenburg, H. (2006). Inter-firm R&D networks: The importance of strategic network capabilities for high-tech partnership formation. British Journal of Management, 17(1), pp. 39-53.

Hohman, M., Gregory, K., Chibale, K., Smith, P., Ekins, S. and Bunin, B. (2009). Novel web-based tools combining chemistry informatics, biology and social networks for drug discovery. Drug discovery today, 14(5-6), pp. 261-270.

Hughes, B. and Wareham, J. (2010). Knowledge arbitrage in global pharma: a synthetic view of absorptive capacity and open innovation. R&D Management, 40(3), pp. 324-343.

Kim, C., Beldona, S. and Contractor, F. J. (2007). Alliance and technology networks: an empirical study on technology learning. International Journal of Technology Management, 38(1-2), pp. 29-44.

King, W. (2009). Knowledge management and organizational learning. Knowledge Management and Organizational Learning, 3-13.

Kofinas, A. and Saur-Amaral, I. (2008). 25 years of knowledge creation processes in pharmaceutical industry: contemporary trends. Comportamento Organizacional e Gestão, 14(2), pp. 257-280.

Laroia, G. and Krishnan, S. (2005). Managing drug discovery alliances for success. Research-Technology Management, 48(5), pp. 42-50.

Mendez, A. (2003). The coordination of globalized R&D activities through project teams organization: an exploratory empirical study. Journal of World Business, 38(2), pp. 96-109.

Nissani, M. (1999). Ten cheers for interdisciplinarity: The case for interdisciplinary knowledge and research. The Social Science Journal, 34(2), 201-216.

Pellmar, T. and Eisenberg, L. (2000). Bridging disciplines in the brain, behavioural and clinical sciences. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press.

Powell, W. W. (1998). Learning from collaboration: Knowledge and networks in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. California Management Review, 40(3), 228.

Roijakkers, N. and Hagedoorn, J. (2006). Inter-firm R&D partnering in pharmaceutical biotechnology since 1975: Trends, patterns, and networks. Research Policy, 35(3), pp. 431-446.

Roijakkers, N., Hagedoorn, J., and van Kranenburg, H. (2005). Dual market structures and the likelihood of repeated ties – evidence from pharmaceutical biotechnology. Research Policy, 34(2), pp. 235-245.

Romm, N. (1997). Interdisciplinary practice as reflexivity. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 11(1).

Roper, A. and Brookes, M. (1999). Theory and reality of interdisciplinary research. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 11(4), pp. 174-179.

Rothaermel, F. T. (2001a). Complementary assets, strategic alliances, and the incumbent’s advantage: an empirical study of industry and firm effects in the biopharmaceutical industry. Research Policy, 30(8), pp. 1235-1251.

Rothaermel, F. T. (2001b). Incumbent’s advantage through exploiting complementary assets via interfirm cooperation. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6-7), pp. 687-699.

Rothaermel, F. T. (2002). Technological discontinuities and interfirm cooperation: What determines a startup’s attractiveness as alliance partner? IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 49(4), pp. 388-397.

Santos, F. M. (2003). The coevolution of firms and their knowledge environment: Insights from the pharmaceutical industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 70(7), pp. 687-715.

Saur-Amaral, I. (2005). Knowledge Management in Multidisciplinary Environments International Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Change Management, 5(5), pp. 9-18.

Saur-Amaral, I. (2009). International R&D: Perspectives from the Pharmaceutical Industry. PhD Thesis in Industrial Management, University of Aveiro, Aveiro.

Saur-Amaral, I. and Borges Gouveia, J. J. (2007). Uncertainty in drug development: insights from a Portuguese firm. International Journal of Technology Intelligence and Planning, 3(4), pp. 355–375.

Saur, I. A. (2005). Knowledge and Information Management: case of a multidisciplinary innovation/R&D initiative. MSc Thesis in Information Management, University of Aveiro, Aveiro.

Senge, P. (1993). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization: Book review. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 45(4), pp. 31-32.

Senge, P. (2000). Classic work: The leader’s new work: Building learning organizations. Knowledge Management: Classics and Contemporary Works.

Skerlavaj, M., Stemberger, M., Skrinjar, R. and Dimovski, V. (2007). Organizational learning culture–the missing link between business process change and organizational performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 106(2), pp. 346-367.

Tashakkori, A. and Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (1st ed. Vol. 46). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Vera, D. (2009). On building bridges, facilitating dialogue, and delineating priorities: a tribute to Mark Easterby-Smith and his contribution to organizational learning. Management Learning, 40(5), 499.