How to implement ‘access to medicine’ AND enhance economic performance: business model options for global access

‘Access to medicine’ or ‘global access’ is at the core heart of corporate responsibility for pharmaceutical companies. Corporate responsibility, however, is not restricted to a philanthropic dimension (such as donations), which is often referred to as corporate citizenship. It also includes corporate social responsibility (in the narrower sense) and corporate governance and thereby paves the way for linking corporate citizenship – “to be a good corporate citizen and contribute to the community” – on the one hand and economic performance on the other hand. In the domain ‘access to medicine’ providing market access to the bottom of the pyramid is an instrument addressing both sides – corporate citizenship (”giving to the public”) and corporate responsibility to its (economic) stakeholders (”creating economic value”).

A. Introduction – What is corporate responsibility?

Corporate responsibility (CR) is becoming a stronghold on board agendas. While sometimes seen as an instrument for communication (and hence being duty of the public relationship departments), companies are increasingly perceiving it as a valuable management tool: it allows for ensuring sustainability including economic and financial sustainability, managing risk such as reputation at stake and enhancing relationship to stakeholders (rather than just focusing on relationship to investors and rather than just establishing one-way communication to non-investor stakeholders). Therefore, it is more a management function, which “at the end of the year” uses its public relation teams to provide for a consolidated communication effort, the company’s sustainability report.

Corporate responsibility basically covers three domains:

- Corporate governance primarily focuses on compliance with (inter)nationally established corporate governance codices. This includes, but is not limited to providing for anti-fraud and anti-corruption countermeasures.

- Corporate citizenship, ‘being a good citizen’, is the company’s voluntary commitment to non-profit activities. This part covers those activities which are usually perceived under the umbrella of corporate responsibility and corporate social responsibility, respectively, such as giving donations and running non-profit foundations for public research.

- Corporate social responsibility (CSR) in its narrower sense addresses the company’s responsibility towards the environment (which focuses on reducing the climate impact of the company’s activities), towards its employees (which focuses on establishing appropriate work safety standards and avoiding, e.g., forced labor and child labor) as well as towards its economic stakeholders, its investors.

The roots of corporate (social) responsibility are in the philanthropic domain. Oftentimes, this led to constellations in which the CR/CSR functions of a company were seen as a part of public relations; subsequently the function itself was and is located in PR departments. It, however, can be used as a very powerful instrument for managing reputation risk. Warren Buffet once said that “it takes 30 years to build a company’s reputation, but it takes only 30 minutes to destroy it”. In the times of fast communication via internet, bad news and bad rumors spread faster than any public relations team can react. Doing something against upfront – reputational risk management – will be cheaper and more reliable.

Analogously, ‘access to medicine’ also is often perceived as being just an instrument of corporate citizenship. The authors will make a case for the idea that the benefits of ‘access to medicine’, however, may go well beyond ‘just giving’. Under certain circumstances, which are discussed in detail below, there is a valid business case for companies to engage here – going even further and beyond reputational risk management towards tangible economic benefits.

Furthermore, the domains discussed before are the ones which are in the centre of discussions surrounding corporate responsibility. Their nature is a rather defensive one – avoiding non-compliance with regulations and expectations, avoiding the impression of egocentric management, avoiding negative reputation. The authors will make an argument for leaving the defensive, exculpatory approach behind and moving towards proactively shaping an economically beneficial surrounding by using the ‘toolbox’ usually associated with ‘defensive and exculpatory corporate responsibility’.

The rationale for this argument can be made clear by one example. This example rests on the assumption that public health is the foundation for economic activity. Countries which were able to ensure general well-being for all their citizens are likely to be those countries which host stable markets. The authors will discuss below that instable markets may be one of the root causes for the lack of ‘access to medicine’ – providing the foundation for public health may help stabilizing those markets and thereby opening the door for a successful market penetration. This example may even go further. Beyond ensuring availability of drugs for ‘neglected diseases’ such an initiative may prevent instability of a company’s stable home ground markets as those ‘neglected diseases’ may very well spread into these home markets and destabilize them.

What is global access?

Before discussing the options for enhancing business models in detail, we want to take a step back and have a look at what global access actually means.

The intensity of public scrutiny against ‘Pharma’ and ‘Big Pharma’ in particular is well known. In those respects, which may be addressed by an ‘access to medicine’ program, there are several aspects and perceptions leading to this scrutiny:

- One major driver is the conflict of being dependent on medical care on the one hand and the enormous profitability of Big Pharma in the past on the other hand. Even in times before the current financial crisis, pharmaceutical companies usually were able to deliver higher shareholder value than most other industries (Angell, 2005). The usually high prices for patented brand drugs can be considered as a major driver for this success. On the flipside, however, these prices will exceed the financial capabilities of third world patients up to parts of first world patients. These potential but not-served patients form a large group of ”neglected patients”.

- The need to continue and outdo the previous year’s success as well as analysts’ expectations has pharmaceutical companies rely on premium priced drugs. This in turn has companies focus on first world markets. Their economies as a whole as well as the individuals are more likely to be wealthy enough to pay the prices of premium priced drugs.

In the consequence, other markets are not served – simply due to the fact that they will not be able to pay the bill. These markets are referred to as ”neglected markets”.

- The aforementioned optimization rule does apply on disease areas, too. If markets, who are not likely / expected to be able to pay the bill, are facing diseases not prevalent in first world countries, there is a very high likelihood that the pharmaceutical industry in general will disregard the diseases and not spend R&D resources on these disease areas. These comprise the so-called ”neglected diseases”.

- Although neglected patients and neglected markets may not be served, they may play an important role in the approval process. In order to obtain drug approvals, large clinical studies have to be performed for drugs and their indications.

It is common among pharmaceuticals to outsource these to offshore service providers in second or third world countries as first world patients are more and more resistant to take part in those trials. The reason for this maybe that they at least have access to other drugs which target the same disease (while being maybe less effective or having more sincere side effects) or the symptoms.

Public critics point out that patients in offshore countries bear the risk of untested drugs while not being able to get those medicines once they are approved (and highly priced; one example for these critics is Shaa, 2006).

The perception of this behavior led to the triad of ‘neglected patients – neglected diseases – neglected markets’. This in turn triggered various initiatives aiming at making medicine available to those, who need it, but cannot afford it: ‘access to medicine’ or ‘global access’.

B. The corporate action plan towards ‘access to medicine’

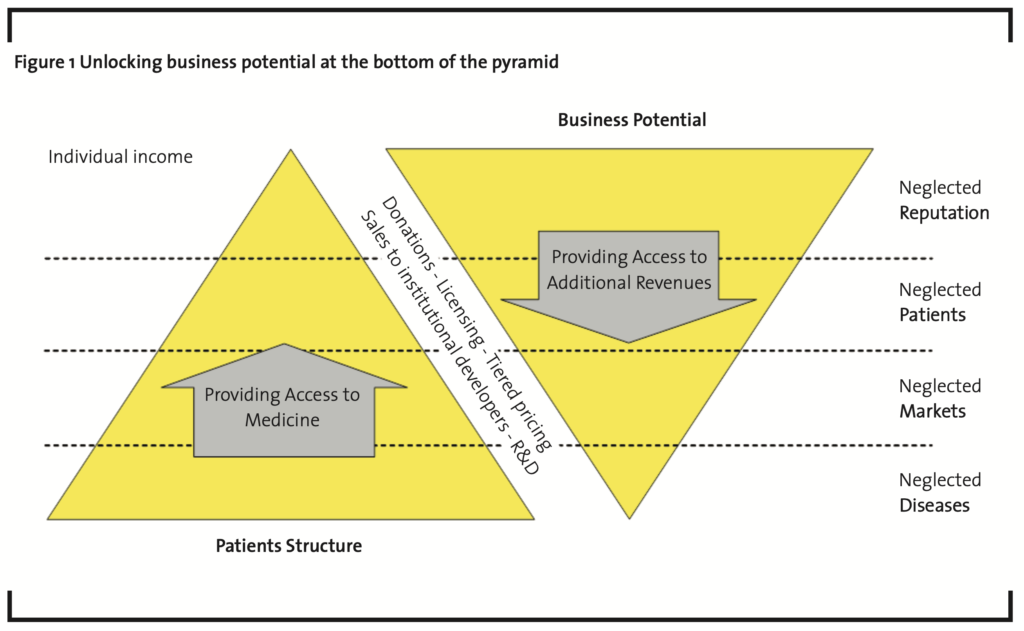

As mentioned before, ‘access to medicine’ is capable of providing tangibly economic benefits, beyond its philanthropic value and reputation risk mitigation. The underlying principle is the fact that all angles of the triad actually are markets. This connection is often depicted as a pyramid (Prahalad, 2004) (Figure 1).

The pharmaceutical industry is perceived as harvesting the ‘top of the pyramid’ only, where a small, but wealthy class of patients resides. Neglected reputation once was the initial driver of ‘access to medicine’ programs and has been well discussed in the past. Working towards the famous ‘bottom of the pyramid’, however, will allow for unlocking new business potential.

Any response to those opportunities, however, has to be embedded in the corporate strategy. Technically speaking, the first step of each action plan is making global access really a part of the strategy. The triad itself defines the set of potential strategy approaches:

- ‘Neglected patients’: The ‘classical’ response is providing drugs for free to particular countries. The business case for such a program usually comes from reducing reputational risk, firing the imagination of brands and the firm’s responsibility as well as replacing marketing expenses in the narrower sense by marginal cost of production which cannot be recovered. The focus of business case modeling will be on defining the appropriate cost of the products given away for free.

- ‘Neglected markets’: A business case for penetrating additional markets – besides contributing to reputational risk reduction and positive marketing effects – usually aims at providing a tangible economic from shifting economic risk towards partners while again ensuring contribution margin from large volumes and low prices. The main success factor for the business case will not be a matter of quantitative modeling but rather than that finding an appropriate operating model which achieves the aforementioned goals.

Besides this primary concept, economic stability may further enhance or provide a ‘brick’ of a neglected markets business model. Serving a market not served before will contribute to public health in the respective country. This may stabilize a market which was avoided before due to perceived or actual instability and hence the initiative may provide the grounds for ‘upgrading’ such a market to a prioritized emerging market.

- ‘Neglected diseases’: Programs in this group focus on researching and developing drugs that are especially relevant for these markets due to climate related conditions or other reasons, and effectively sold at a low price in those very large markets. Business cases here focus on providing contribution margin for overhead (incl. R&D) by increasing volume. If the volume is large enough, the product of price and volume less the marginal cost of production may provide sufficient contribution margin for recovering the associated R&D cost as well as associated overhead cost for production and administration. The rather intangible benefit of reducing reputational risk as well as the rather tangible benefit of being able to replace marketing cost may be achievable here, too. The key success factor of business case modeling will be defining the set of costs which need to be recovered.

Beyond this primary approach, there may be a long-term benefit, too. Neglected diseases are not restricted to third world markets far away anymore. Globalization may carry a disease into a first world market; climate change may pave the path for such a disease to advance to first world markets. Having a drug on the shelf in such a case will be a competitive advantage.

Based upon the strategic decision which opportunity to chase, the business case – both in terms of the operating model and in terms of the targeted financials – needs to be translated into an operational plan. Upfront a case will have to be made for each of those options.

In order to make business case modeling successful two requirements have to be fulfilled. At first, the business case needs – despite the intangible effects which significantly contribute to the benefits – to provide a true and fair view in order to truly support decision makers. Secondly, the business case has to be able to gain the support needed and thus has to be able to work out the actual benefits. The strategy approaches stated above and their benefits will be discussed in detail in the following sections giving particular attention on how to ensure successful business case modeling. (It shall be noted that the following analysis of how to establish a business case is focusing on ‘hard’, tangible economic benefits. The reader should keep in mind that those tangible benefits usually will be accompanied by soft factors, such as positive image / brand effects as well as reduction of reputational risk.)

C. Business enhancement at the bottom of the pyramid neglected patients

Being aware of their responsibility pharmaceutical companies responded to the challenge in various ways: Merck Co. brought its ’Medical Outreach Program’ to life which ensures the availability of vaccines, which originally were developed for first world markets, in third world countries. The total of relief contributions for this program amounts up to 3.3 billion USD according to the company’s corporate responsibility report of 2008. The program reaches a number of 104 countries across three continents (Merck & Co. Inc., 2007).

Bristol-Myers Squibb’s ’Secure the Future’ program goes a step beyond. The program built ‘fully fledged’ communities for HIV patients in Africa, where they do not only receive required medication (out of Bristol-Myers Squibb’s brand drug portfolio), but are also given a social home.

While it might seem that this kind of program only triggers cost and negatively impacts the bottom line, we argue that there is the benefit of positively impacting the company in terms of reputation risk. The transmission mechanism for translating the intangible benefit of reduced risk into a tangible one was researched and also proven by studies (see, e.g., Bartram, 2001): a company’s value is determined by discounting its expected future cash flow; the discount rate will include a risk premium, which can and will be reduced by mitigating the risk drivers upfront which might turn into losses in the future. Hence, in the long run, any risk reduction will positively impact corporate value.

Beyond its origin the approach, however, is not restricted to third world patients. Pfizer, for example, runs a similar program (‘Maintain’) for U.S. patients in need. Pfizer first set up a patient-assistance program for as early as in 2004 (Pfizer, 2007). In the wake of the financial crisis in 2008/9 Pfizer is extending this program to those who lost their job and subsequently their health insurance due to the financial crisis and thus cannot afford prescription drugs anymore.

It should be noted, however, that Pfizer’s program does not cover all prescription drugs (Miley and Thomaselli, 2009). Major oncology drugs, for example, are not included although usually being the ones which are far more expensive. This issue in combination with communicating total cost figures based on list prices once again put those programs under scrutiny. Thus careful design of the business case, which should serve as the platform for the communication strategy, too, is suggested.

Key success factors for successful business case modeling

The first hand benefit of such a program seems to be clear: it is its public relations value. The cost of such a program deserves a more thorough look. Pfizer claims the cost of its preceding program to amount to 4.8 billion USD (Miley and Thomaselli, 2009). This figure is based on the list price of the drugs. This approach, however, may be misleading: The benefit of such a program can, but should not be compared to the revenue usually associated with the products which are now given away for free, as opportunity costs do not arise. Production given away for free is not crowding out production which would be associated with revenue. Rather than that production associated with revenue does simply cease as the market itself has vanished. Thus revenue at list prices will not occur anyway.

We make an argument for considering marginal cost of production instead. (For the sake of completeness, it should be noted that the argumentation stated above must not conclude that no cost occur as there are no opportunity cost. The actual cost of production does occur.) These are defined as the change in total cost that arises when the quantity produced changes by one unit. This approach, however, has to answer the question, why the business case should leave the principles of multi-period product life cycle costing and neglect major cost items – research & development and marketing.

- The role of R&D: Any business case for such a program must be distinguished from a business case for a product or target disease area. Drugs given away for free should not be charged with the cost for R&D, as these customers would never be able to purchase the product and hence would never be able to contribute to R&D. Hence, considering R&D cost amortization as part of the business case will be misleading. Putting it the other way round, this principles claims that R&D expenses have to be paid out of ”regular actual revenue”.

- The case of marketing expenses: They usually comprise a major part of a pharmaceutical company’s expenses (Consumer Project on Technology, 1999). They must not be allocated to the business cost case for such kind of programs, as the recipients in Pfizer’s program – must have been prescribed those drugs prior to entry in the program. In this constellation marketing is not necessary by definition as the marketing effort relating to this single transaction has taken place before. Thus marketing expenses are not related to the program’s benefit at all and hence should be excluded from the analysis.

Considering the aforementioned communications aspects, these paradigms should be considered upfront and also should be part of the associated marketing campaign. Critics will point out pretty soon that the opportunity cost (based on list prices or let alone on an excessive cost base) allocated to the program are fictional, in particular due to the ”lack of market” argument.

Other benefits might be considered on the income part of the business case:

- Production volume: The additional turnover resulting from products given away for free may increase overall turnover and hence reduce the fixed cost portion of the cost of goods sold.

- Revenue from cost reduction: The overall benefit will come from ‘paying’ contribution margins to the production facilities out of a de facto PR cost reduction.

- Reduction of tax burden: The additional production which is associated with cost but not associated with revenue may decrease overall taxable profit. This in turn will reduce the tax burden. In addition to this, companies may be – depending on the respective tax regimen – able to claim further tax reductions for donations based on the value of their products given away for free (which, of course, has to be properly valued in line with the considerations above).

Considering both tangible and intangible elements a positive business case for any such program is not out of reach.

D. Business enhancement through new distribution channels – neglected markets

The second strategy approach mentioned before aims at serving neglected markets with existing products. Let us consider the following company:

- The drug to address a focal disease of a neglected market is readily available.

- The drug could be provided at an affordable price (see constellation in the previous section).

Despite having products ready our company may still be scared off from some country markets by various reasons:

- The political environment may not be stable enough to justify building a production facility there, while utilizing a local licensee would put the intellectual property at severe risk.

- The delivery requires a highly efficient supply chain in order to make the price affordable; due to the political risk mentioned before, the efficiency cannot be achieved due to required security measures.

- Distribution channels may not be safe. This creates a heightened risk of feeding the grey market in the first world rather than serving the targeted patients.

As stated in an earlier section, the main success factor for the business case for a solution here will not be a matter of quantitative modeling but rather than that finding an appropriate operating model which tackles the aforementioned problems. Economically speaking, the operating model must allow for eliminating the risk or shifting risk towards partners while again ensuring contribution margin from large volumes and low prices.

Thus the established and well understood distribution models for pharmaceutical companies are up for discussion themselves. ‘Thinking out of the box’, collaboration with new partners – new in the meaning that they are not only new to the company, but new to the industry in general – will be the key:

- This might go as far as using the distribution channels of first world consumer product companies, e.g. the well-known soft drink manufacturers, for the distribution of products. The rationale here is that they need to tackle security issues as well.

- Establishing new distribution models even might involve Big Pharma’s natural enemies – those non-government / not-for-profit organizations who point to the dark spots on the industry’s clean records and engage in the ‘access to medicine’ discussions. These organizations know the markets and the issues and therefore may be utilized as monitoring agency in the process.

This theorem can be extended further: the key success factor for any new distribution channels will be for the moment the role of NGOs in general. Establishing a new distribution model in order to serve neglected markets is more likely to be successful when supported by a concerted effort by pharmaceutical companies, distributor companies, national governments as well as agencies and others. Experience indicates that there is a high risk of power games between these players. The NGOs – if not considered as actually being involved, e.g. as a monitoring agency, in the actual distribution process – may still be the missing piece here. They may serve as the neutral intermediary between the diverging entities as their primary focus – per definition – is not profit. Hence, a case can be made for collaborating with those NGOs in an orchestrated way to become active players in the process for effective and efficient access to health.

Key success factors for successful business case modeling

As mentioned above, establishing a business case here will need to combine different elements, partially from the previous sections:

- The business case itself will have to put significant weight on a thorough risk assessment.

- A pricing model should be / can be defined, which provides for positive contribution margins.

- The distribution model actually has to be a ‘new one’. It may include and combine the whole array of instruments here: donations, licensing, tiered pricing, sales to institutional developers, etc.

- Any such new distribution model will involve external partners.

Following the concepts described above (considering marginal cost of production rather than total cost, focusing on contribution margin accounting and appropriate consideration of soft factors, including reputational risk) business cases here still will provide significant upside potential.

Similar to the (more obvious) case of neglected diseases discussed below, a longterm benefit of this strategy may arise besides this short-term ‘hard fact benefit’. There is a (although possibly weak) reciprocal link between serving neglected markets and the status as a neglected market. The basic assumption of this theory is that serving a market which is neglected and not served yet because of its instability will contribute to public health and to general well being of the respective public in the respective country. This in turn may contribute to stabilizing a formerly instable market. Thus a neglected market may turn into a desirable target market giving further rise to the validity of the business case.

E. Business enhancement through product structure – neglected diseases

A major example for a successful program in the ‘neglected diseases’ domain is Novartis fight against Malaria. Novartis enforced its Malaria research, although Malaria is not prevalent in Novartis’ primary markets. The cornerstone of this program is providing drugs at a very low price to very large market.

One goal behind this initiative is clearly corporate responsibility, as Novartis is highly aware of the death toll Malaria is still causing outside the first world. The program, however, is a good example for an approach which goes beyond purely serving a corporate citizenship purpose – such efforts may not necessarily be solely investments without return. ‘Neglected diseases’ can very well be profitable disease targets for companies, as the required low price may be offset by the enormous number of patients.

The experience of GlaxoSmithKline proved the validity of this approach (Financial Times, 2009). According to GSK, price cuts of 30-50% had volumes increase by 15-40%; the price reduction of one particular drug yielded a sales increase by 700%.

Key success factors for successful business case modeling

The key lever for a business case for such a program is going away from a total cost of product point of view towards a contribution margin oriented approach. The principle of contribution margin accounting is computing what a product’s revenue less the cost directly incurred by producing the product (usually variable costs) contributes to covering the fixed cost of operations and administration. The case of negative contribution margin shows that the product does not even cover its direct (variable) cost neither does it contribute to covering the fixed cost of the company.

In practice, this principle is applied by defining different ‘layers’ of a company to which costs can be directly allocated. Direct cost of production can be allocated to a single product instance, so that a ‘contribution margin I’ (CM I) is computed for the product. Overhead cost of production and sales may be directly allocated (without using allocation keys) to a division level, so that a ‘contribution margin II’ (CM II) is computed for a division by putting the margins of each product of the division against the related overhead and so on.

Applying this principle here aims at creating a positive contribution margin for a particular product by achieving a volume large enough so that the (mathematical) product of price and volume provides at least a positive contribution margin and – in the best case – a margin which substantially contributes to the division’s cost. If such a situation is achieved, the bottom line impact is positive by definition.

The pricing decision itself again must not be based on the total cost of the product. The aspects of using total cost are ‘covered’ by using the contribution margin accounting approach instead.

Besides this short-term ‘hard fact benefit’ a long-term benefit of this strategy may arise, too. Developing a drug for a third world market does not necessarily mean that the drug will not be used in first world markets. As global epidemics in the past (e.g. SARS) have shown, diseases may spread into first world markets. Having drugs ready in the cupboard certainly will ‘help’. The scenario may be considered as far fetched thought. Globalization, however, is just one driver for such developments. Climate change is a fact and will also give rise to diseases from warmer climate zones in places where they are not expected now.

These ideas might be given consideration in the business case at product level, although the impact will be of qualitative nature only – it will be nearly impossible to reliably define a hard quantitative impact for such a case.

F. Conclusion

Due to its importance and its impact on personal level ‘access to medicine’ / ‘global access’ deserves maximum attention by the pharmaceuticals industry and also needs to consider new approaches, which to some extent have to be created ‘out of the box’. ‘Access to medicine’ is oftentimes seen as a topic which is part of corporate responsibility and belongs to corporate citizenship in the model depicted above. Nevertheless, it helps the case to create ways which allow for serving the initial purpose – providing access for those who otherwise would get no medication – whilst providing economic benefit at the same time. This will require new coalitions in an orchestrated approach, but also creativity in terms of upfront business modeling.

Besides this result, the concepts discussed above may lead to an additional conclusion. The different types of response to the ‘access to medicine’ challenge are a result of corporate responsibility in the first place, but also fitting and shaping economic needs. Thus, the authors make – independent of the industry a company is competing in – a case for considering corporate responsibility as a major management tool to be used when a company is facing adversity.

This theory is supported by evidence from the current financial and economic crisis: on the one hand the lack of responsibility of the financial industry towards non-shareholding stakeholders was a major driver of the crisis. On the other hand, using the toolbox, which is provided by corporate responsibility, companies avoid getting even deeper into troubles (e.g. by financially supporting suppliers in major financial woes as seen in the automotive industries) or getting out of the current situation (e.g. by entering low-profit markets or markets which just allow for recovering the costs and thereby ensuring the required utilization of production facilities).

Generally speaking, the corporate responsibility toolbox is a valuable instrument for shaping the corporate future aligned with its strategy. This is true for the strategy options discussed above, for which corporate responsibility can be transformed into a valid business case. In particular the theory holds true for the concept of stabilizing markets through general health improvement by serving neglected markets. Any value-based performance management instrument, such as economic value added (EVA), is incorporating risk into its formula. Thus stability as the counterpart to risk is driving economic success. It is, however, not limited to creating stability in neglected markets – addressing neglected diseases may in the long term ensure stability in first world markets as they need to be prepared for new diseases. Globalization and climate change may pave the diseases’ path into the first world. Contributing to have one’s home market be prepared may be one piece of the EVA puzzle.

Pharma’s corporate responsibility toolbox in the ‘access to medicine’ domain can provide for another contribution to shaping the future. Entering areas not served before also helps understanding a new area and open the door to a new field for innovation. Biology, for example, was ‘neglected’ by Big Pharma in the past – nowadays the biotech revolution can be considered one of the drivers of the health care industry. Understanding areas not understood before hence will be a driver for innovation in the future. This shall not comprise a case for patenting natural medicine and natural healing methods, but for serving neglected areas – patients, markets and diseases – and learning from this experience to shape your own future.

These are examples for the power of corporate responsibility. For this reason the authors expect that the current crisis will strengthen the need for corporate responsibility across industries, as value generation from corporate responsibility will be more visible and more appreciated these days than any time before.

REFERENCES

Angell, M. (2005): The truth about the drug companies: how they deceive us and what to do about it, Random House, New York, USA.

Bartram, S. M. (2001): Corporate risk management as a lever for Shareholder Value creation, Working Paper. Consumer Project on Technology (1999): Drug company expenses broken down by cost, marketing, and research & development, available at http:// www.cptech.org/ip/health/ econ/allocation.html, accessed 14 Jul 2009.

Miley, M., Thomaselli R. (2009): Will Pfizer’s free drug program give PR lift to Big Pharma?, available at http://adage.com, accessed 14 May 2009.

Merck & Co., Inc. (2007): Listening, responding and working toward a healthier future (Corporate Responsibility 2006-2007 Report), available at http:// www.merck.com/cor porate-responsibility/cr-printreport.html, accessed 14 July 2009.

Financial Times (2009): GSK to cut prices of medicines in emerging markets, available at http://www.ft.com, accessed 12 June 2009.

Pfizer Inc. (2007): Strong actions (2007 Corporate Responsibility Report), available at http://www.pfizer.com /responsibility/grants_payments/corporate_responsib ility_report.jsp, accessed 14 July 2009.

Prahalad, C.K. (2004): The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid, Wharton School Publishing, Philadelphia, USA.

Shah, S. (2006): The Body Hunters: testing new drugs on the world’s poorest patients, The New Press, New York, USA.