Impact of tightened environmental regulation on China ́s chemical industry

Abstract

Environmental regulation of China ́s chemical industry has tightened considerably in the last few years, both with regard to the amount of regulation introduced and the severity of its implementation. This has had an effect on a number of aspects of the industry including the number of chemical producers, the location of chemical production, the prices of chemical products and the technology used for chemical production. The paper discusses these and other aspects as well as the impact on individual chemical companies and the underlying government objectives.

1 Introduction

Improving China ́s environmental situation is one of the key themes of Chinese president Xi Jinping. For example, at a study session attended by members of the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee in May 2017, Xi stated that the country should protect the environment “like one protects one’s eyes” and treat the environment “as one treats one’s life” [1]. This focus is likely to be the result of an increase in GDP per person accompanied by the adaption of middle-class interests and concerns, such as happened in Western countries a few decades earlier. Presumably strengthening environmental protection as a government objective is partly done to prevent dissatisfaction of the population, which could even lead to political movements similar to the “green” movement in the West.

The 13th Five-Year Plan covering the period of 2016-2020 was a particular turning point in increased environmental protection after some earlier attempts to focus on this topic, such as the introduction of a “Green GDP” figure, were not fully implemented due to the high revealed cost of environ- mental pollution in China [2]. The 13th Five-Year Plan includes green development as one of the five key development concepts for China [3]. Compared to previous plans, it increases the number of green development quotas and enacts a stricter implementation process.

Indeed, additional regulation combined with stricter implementation has been the key feature of China ́s enhanced environmental protection in the past two years.

1.1 Additional Regulation

Key regulatory changes within the last two years include a massive program of shifting chemical production to chemical parks, restrictions on the location of chemical production near the Yangtze river, the tightening of rules for many individual substances and substance classes and the introduction of an environmental tax, all overseen by a strengthened and renamed ministry.

The goal of shifting chemical production to chemical parks was first outlined in the 13th Five-Year Plan for the Chemical Industry (Petroleum and Chemical Industry of China, 2016), in which it is stated that during the period of the plan “the rate of new established chemical industrial enterprises entering the park will reach 100%, and the relocation of the enterprises outside the parks shall be accelerated”. These high-level guidelines were later specified in more detail, providing a timeline for the different sizes of chemical companies. In addition, the guidelines were transferred from a central level to the provincial level. For example, Fujian province in 2018 enacted the “Implementation Plan for the Relocation and Renovation of Dangerous Chemicals Production Enterprises in Urban Densely Populated Areas”, which states that small and medium-sized enterprises and large enterprises with major potential risks will start relocation and reconstruction before the end of 2018 and be completed before the end of 2020 while other large-scale and extra-large enterprises will start relocation and reconstruction before the end of 2020 and will be completed before the end of 2025. Other provinces including Anhui, Gansu, Guangdong, Heilongjiang, Henan, Jiangsu, Ji-lin, Shaanxi, Shanghai, Sichuan, Tianjin and Zhejiang have enacted similar guidelines. Some provinces even indicate target figures for the share of chemical enterprises to be located in chemical parks by 2025, aiming to reach 90% or higher from the current nationwide 45%.

At the same time, there is the objective of regulating or even reducing the number of chemical parks. The 13th Five-Year Plan for the Chemical Industry states that “in principle, no new chemical industrial parks will be established”. Indeed, some Chinese provinces have initiated the process to close or revoke chemical industrial parks (Dextra International, 2018) , with some industry participants expecting the number of chemical parks to go down to about 480 by the end of 2018 from the 601 chemical parks existing at the end of 2017 (Cinn.com, 2018). However, given the fact that the number of chemical parks in- creased by almost 100 from the end of 2016 (502 parks) (Eastmoney.com, 2018) to the end of 2017 despite the objective of not increasing the number of chemical parks, this is a somewhat risky prediction.

Certainly, there are such developments on the level of individual provinces. Shandong province has announced the goal of halving the number of chemical parks in the province to 100 (ICIS, 2018). A first step towards this goal was the certification of 31 chemical parks as qualified. A second and third list of qualified chemical parks in Shandong are expected to be announced by the end of September and December (Liu, 2018). Shandong may serve as a model as it is reported to both have a low share of chemical companies located in chemical parks (37%) and a high share of GDP depending on the chemical industry (20%) (Liu, 2018).

In any case, the goal of controlling the number of chemical parks indicates that the objective of the re- location is not only to avoid chemical production being located close to population centers, but also to allow for a better control of the individual chemical companies therein, in particular with regard to their environmental efforts.

Even within some chemical parks, limitations have been imposed with regard to the location of chemical production, particularly in the Yangtze area. Chemical industry projects have been prohibited within one kilometer of the Yangtze and its major tributaries (International Rivers, 2018), a regulation that also applies within chemical parks near the river.

Apart from regulating the location of chemical production, the regulation of emissions and of energy consumption has also tightened considerably. For example, the Ministry of Environmental Protection has published Emission Standards of Pollutants for Calcium Carbide Industry, which came into effect on July 1st, 2018. When discharging air and water pollutants, existing and new producers are to comply with these standards, which are the first to specifically apply to calcium carbide (China Chemical Reporter, 2018b).

Similarly, regulations are enacted further downstream, often on a provincial level. For example, from the beginning of 2019, the use of water-based coatings will be mandatory for motor vehicle maintenance companies operating in Tianjin. In July 2018, Hebei province implemented new emission limits on water pollutants. These limits are expected to reduce chemical oxygen demand by 32.9% and ammonia nitrogen emissions by over 58% from the 840 chemical firms in the province (ICIS, 2018).

Such provincial-level measures also indicate that the provincial governments now seem to compete with each other based on their environmental credentials (China Chemical Reporter, 2018b). The government will also check if key firms in high energy-consuming industries – including more than 2000 chemical and petrochemical companies – have reached the mandatory energy consuming standards, and sanction those companies not following the regulation (China Chemical Reporter, 2018c).

Taxation is employed as another tool to improve environmental protection. In 2018, an environment tax was introduced. Under this regulation, pollution of soil and air are taxed under a uniform set of national rules instead of the previous system of pollution fees on a local level. As the new tax is imposed by the central government and not as previously by local governments, it is easier to implement and not likely to be easily waived for political or economic considerations. The environment tax varies by pollution type, location and severity and covers both air pollution and noise pollution. An official study expects revenue from this new tax to at least double compared to the previous pollution fee system (South China Morning Post, 2017). The new system also provides incentives for polluters to reduce emissions, as the tax on emitters if reduced if their emission volumes are substantially lower than the permitted limits.

Finally, the intensified efforts to mandate environmental protection in China are also reflected by changes in the responsible government organs. Specifically, in March 2018 new China Ministry of Ecological Environment replaced the previous Ministry of Environmental Protection, which itself had only been promoted to the rank of a ministry in 2008. The new ministry has added responsibilities for climate change, agricultural pollution, marine ecology and related issues, which were previously scattered across varies government organizations. The increased responsibilities of the ministry highlight the growing importance of environmental protection in China and should simplify the focus on these efforts by putting them under a unified control.

1.2 Stricter Implementation

In the past, improving the environmental situation in China often faced huge obstacles as implementation of environmental regulation proved to be difficult on a local level, partly as local government officials were primarily incentivized on the basis of economic growth and thus tended to overlook environmental violations that were felt to facilitate faster growth. However, in July 2016 a nationwide campaign of environmental inspections was started, focusing on a few selected provinces at any given time. These inspections are far stricter than in the past as they are unannounced and often followed by fines and/or temporary production stops. These strict inspections are likely to be the key difference to previous environmental efforts as for the first time, regulations are actually implemented without major exceptions. The anti-corruption campaign started by Xi Jinping supports these environmental efforts as the evasion of regulation via bribery and/or local connections has become much more difficult. In addition, about 15,000 government officials so far have received punishments after the inspections. As a consequence, some observers in Western chemical companies now report that close relationships to local authorities are no longer vital as government authorities follow a strictly rule-based approach. Another round of inspections has started on June 11, 2018 and will continue until April 28, 2019, covering many of the most important chemical production areas in China (Xu, Stanway, 2018). The resources to execute these inspections were increased to two hundred teams with a total of about 18,000 inspectors and support staff, showing the determination of the central government to insist on strict implementation of the regulation.

The stricter implementation will also cover waste disposal by chemical companies. The government has launched nationwide inspections covering the transfer and disposal of waste, and companies not able to meet the standards for waste disposal will not be allowed to move into chemical parks, which in itself is a precondition for being allowed to con- tinue production in the longer term. After some initial failed inspections, mayors of seven Chinese cities were ordered by the ministry to improve their system of disposing chemical and other hazardous waste (Xu and Mason,2017).

2 Impact on China ́s chemical industry: Factors

We will now examine the impact the above tightened environmental regulation has had on the chemical industry primarily in China, but also overseas.

Key aspects include factory closures, factory relocations, plant modifications, capacity reductions/reduced operating rates, technology changes, higher prices, shift from export to import, changes in approval practice for new chemical plants, impact on foreign competitors, changes in industry structure, changes in mindset, and opportunities for Western companies.

Due to the large number of chemical companies in China, the rapidly changing landscape and the limited information available on some companies, these aspects cannot be covered comprehensively but will instead be highlighted via individual examples.

2.1 Factory Closures

Closures of chemical plants are the most visible indication of China ́s tightened environmental regulation. They arguably have the largest impact on the chemical industry as the capacity of the plants closed is eliminated from the industry.

Examples include the following.

Anhui province will close six chemical plants (Suratman, 2018).

In Heilongjiang province, 14 chemical plants will be closed down (Zhang, 2018).

Jiangsu province plans to close 2077 chemical plants in 2018. The province was under intense scrutiny in a round of inspections in April/May 2018, during which a number of listed chemical companies including Nanjing Chemical Fibre, Lianhe Chemical Technology, Jiangsu Yabang Dyestuff and Jiangsu Yoke Technology were found to violate environmental protection regulation (Suratman, 2018; Zhang, 2018). In one specific city, Changzhou, 40 chemical plants were closed within the first few months of 2018.

Shandong province is targeting to close 20% of the 4930 chemical plants located in the province (Suratman, 2018).

Sichuan province plans to close nine chemical firms (Xinhua, 2018).

Yichang city in Hubei province has closed down 25 chemical plants since 2017 (Xinhua, 2018).

The plants closed down come from different chemical segments. Many of them are producers of basic chemicals while others are mainly involved in downstream activities such as formulating chemical products (e.g., paints). High-ender chemical companies seem to have been largely spared so far. In fact, information from a number of Chinese industry participants and observers points to the fact that many of the companies closed down do not only contribute substantially to environmental pollution but also suffer from economic problems such as low profitability, low capacity utilization and low quality of the products produced.

According to the China Petroleum and Chemical Industry Foundation (CPCIF), the number of chemical and petrochemical companies in China with annual revenues above 20 million RMB decreased by 1666 from 29307 companies to 27641 companies (-5.7%) from the end of June 2017 to the end of June 2018 (China Chemical Reporter, 2018f). Most of the closures were for chemical companies (-1565) rather than for refining or oil and gas companies. During this period, the revenue of the chemical industry increased by 12.4%, the profit rate increased from 6.1% to 7.1% and average capacity utilization for a basket of 28 chemicals increased by about 3% to 72%. While there are other possible reasons for these company closures, it is likely that the tightened environmental regulation played a major role, particularly as these closures happened during a period of increasing profit, sales and capacity utilization.

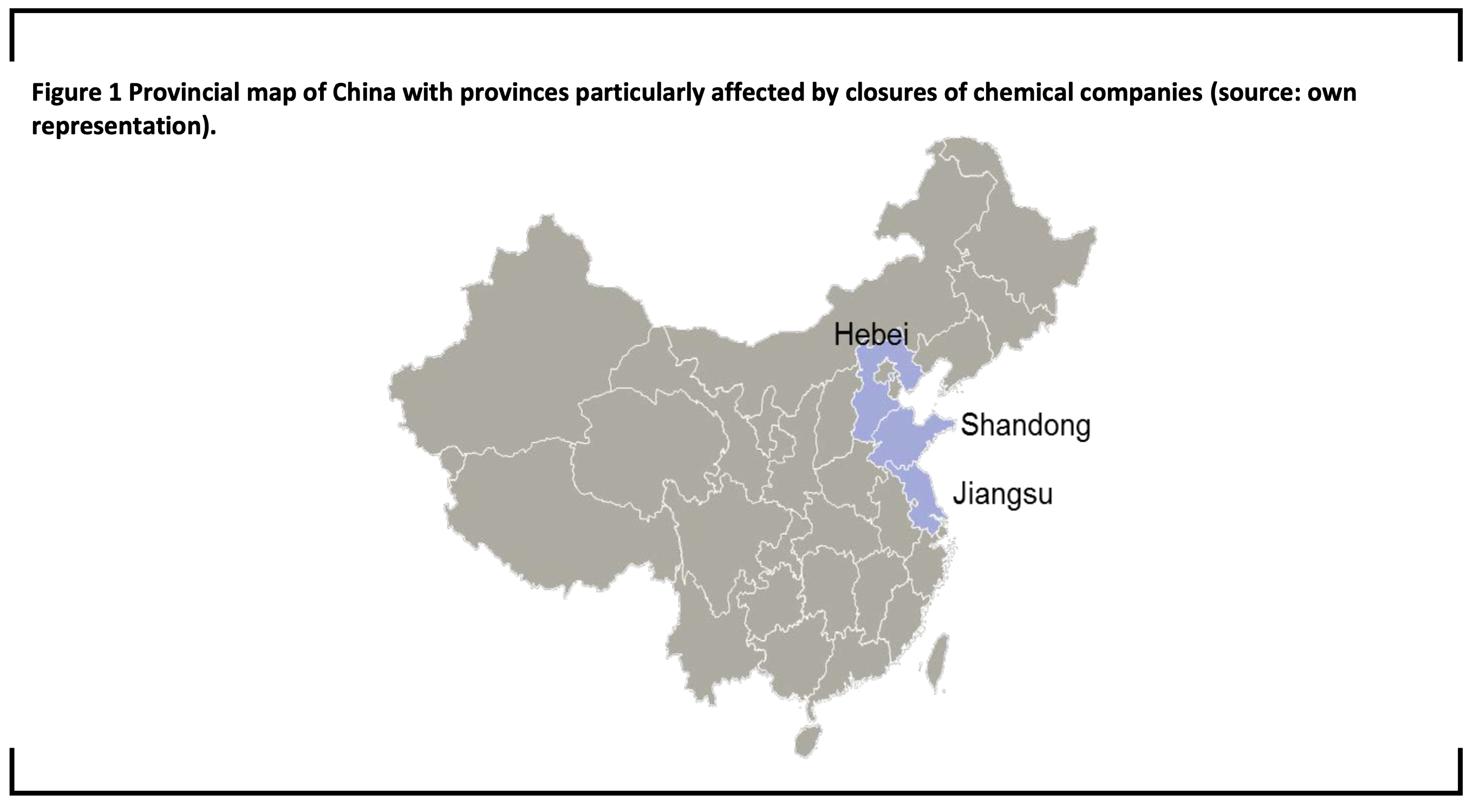

So far, the coastal provinces of Shandong and Jiangsu have announced the most wide-ranging plans for factory closures (see Fig. 1). In addition, due to its closes proximity to the Beijing/Tianjin cluster, Hebei province is also likely to close a substantial number of chemical factories. In addition, it is very likely that other provinces – first those on the Chinese seaboard, but later also inland provinces – will increasingly be affected.

2.2 Factory Relocations

While not as harsh as closing down a factory, the requirement for relocation into a chemical park also has substantial consequences for those chemical plants affected. These include the need to identify and secure space in an approved location such a chemical park, the shift of existing production equipment to the new site or the investment in new equipment, and frequently the acceptance of tighter emission regulation at the new site, which may require further investment in emission control. Apart from the direct costs of such a relocation, indirect costs include the possible interruption of production if the equipment is relocated, the time needed to secure a smooth production process at the new site, and the potential loss of qualified workers not willing to work at the new site. Depending on the local importance of the chemical plant affected, local government may financially support the relocation.

Several provinces have indicated numbers of chemical plants to be relocated. Typically, these numbers are larger than the number of plants being closed. Examples are given below.

In Anhui province, 34 chemical plants are to be moved into chemical parks (Suratman, 2018). Heilongjiang province will relocate 5 chemical plants (Zhang, 2018).

Sichuan province will relocate 37 chemical plants (Suratman, 2018).

A number of producers of sulfuric acid will relocate their production. Companies include Hubei Zhongfu Chemical Industry Group Co., Ltd., Yichang Xinyangfeng Fertilizer Co., Ltd., Xiamen Xiahua Industrial Co., Ltd. and SinoChem Fuling Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. The total capacity to be relocated will be over 8.00 million t/a. (China Chemical Reporter, 2018d).

Relocation may not be straightforward for all chemical companies. At least in the Eastern provinces, chemical parks are becoming increasingly restrictive with regard to the companies being allowed entry, with refusal rates of 60-70% not uncommon. Criteria applied include the environmental pollution of the chemical plant as well as the investment planned in the chemical park, effectively creating additional entry barriers for smaller chemical companies, particularly in highly polluting chemical segments. For example, the government of Shandong province will limit the approval of the production of hazardous chemicals to projects with an investment of at least 300 million RMB (about 40 million Euro) (China Chemical Reporter 2017).

Some relocation may be done proactively, particularly if it is combined with a capacity expansion which would not likely have gotten approval at the historical site. For example, in July 2018 AkzoNobel Specialty Chemicals broke ground on a new organic peroxide production facility in Tianjin, China. It will be located in the Tianjin Nangang Industrial Zone. According to the Akzo Nobel press release, the new plant “supports efforts being made by Chinese authorities to optimize urban planning and produce an industrial upgrade in the country’s chemical industry” (Akzo Nobel, 2018). This presumably refers to the government relocation plan for the chemical industry in China.

2.3 Plant modifications

The typical outcome of plant inspections is not a shutdown or a forced relocation, but rather a request for a modification of existing processes in order to lower emissions. Frequently these require shorter production stops (e.g., a few weeks) and some investment in emission control. For example, while Heilongjiang shut down 14 chemical plants and required relocation of 5 plants, a total of 69 plants were requested to modify and upgrade their processes (Zhang, 2018b). Typically, such modifications do not result in a longer-term capacity reduction, but they may increase production costs.

2.4 Capacity reductions / reduced operating rates

Frequently companies had to reduce their operating rate and thus their overall capacity as a result of government restrictions on emissions. An affected segment is Chinese caustic soda production. In this segment, environmental inspections were reported to lower operating rates to around 70%, and sometimes even to 50% (Han, 2018).

While China theoretically has an overcapacity of maleic anhydride, restrictions on emissions led to shortages in production as the theoretical capacity was only utilized at 50-60%. This resulted in short-ages of the chemical in Europe, which depends on imports from China (Beacham, 2018).

2.5 Technology changes

There are several important chemicals which can be produced by more than one economically viable route. In fact, the use of coal as a raw material replacing naphtha is one of the key characteristics of the chemical industry in China as compared to the industry in the Western world, owing to the relative lack of oil resources and the relative abundance of coal in China.

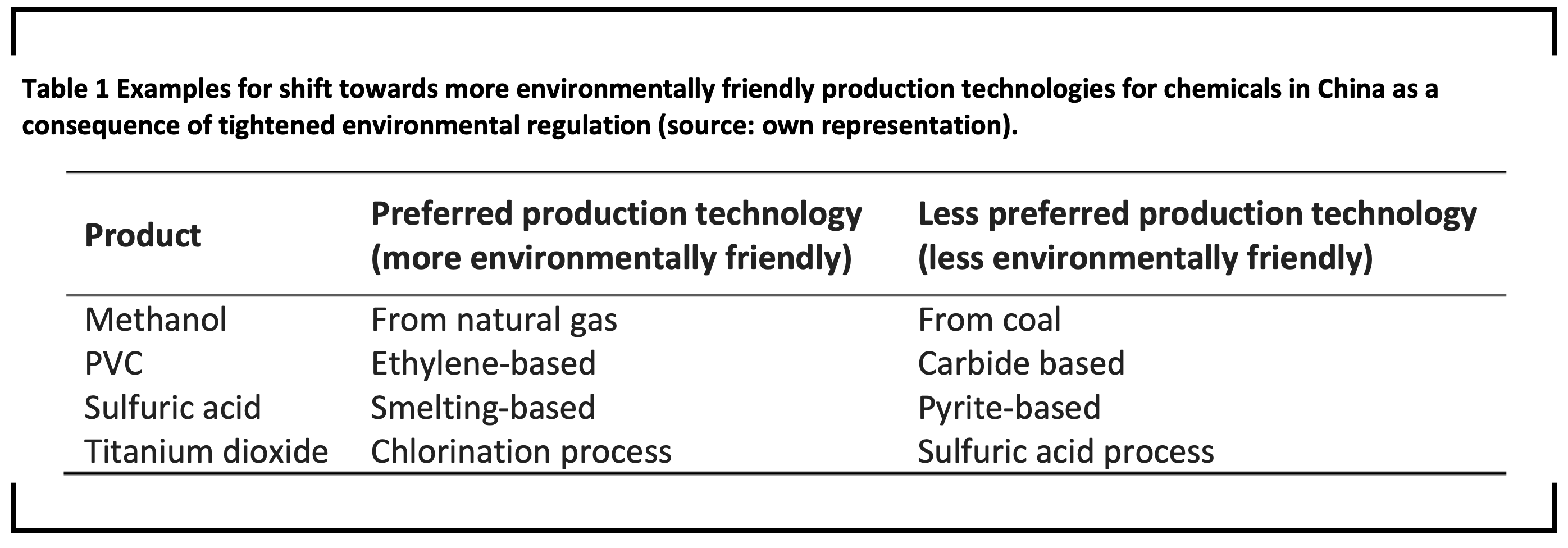

The different production routes typically do not have the same impact on the environment. As a consequence, the tightening of environmental regulations in China will lead to a shift towards the more environmentally friendly technology. Frequently this is the technology that is already being favored in the Western world. The table below gives some examples for such a technology shift as a consequence of tightened environmental regulation in China. The shift may either happen by closing down plants based on the less preferred technology, or by only approving the preferred technology for new plants, or by a combination of both.

A similar shift also occurs on the level of product technology. For example, government policy favors water-based coatings over solvent-based coatings, and the target for 2020 (as stated in the 13th 5-Year Plan) is to reach a 57% market share of water-based coatings from the 46% share it had in 2016.

2.6 Higher Prices

Predictably, the capacity closures and restrictions on operating rates have caused prices for some affected chemicals to rise substantially. Dyestuff prices in China rose substantially in 2017. For disperse dyestuffs the 2017 price increases were as high as 25%-37%. Dyes are a segment particularly affected by the tightening of environmental regulation, as traditional dyestuff production creates large amount of waste water. As a consequence, a number of companies had to shut down, leading to the price increases observed (China Chemical Reporter, 2018e).

Similarly, the spread between the raw material toluene and toluene di-isocyanate was close to the highest spread since 2000. This was reportedly a consequence of the 2017 winter air campaign, which caused a tightness for natural gas as the use of coal was limited in order to improve air quality. Subsequently, local authorities halted supply of natural gas to PU manufacturers (Richardson, 2018).

Caustic soda is also among the chemicals affected by increased environmental regulations in China, with prices having almost doubled between 2016 and 2017 (Han, 2018).

2.7 Shift from import to export

An interesting effect of the reduced production of some chemicals as the consequence of increased environmental regulation is that China in some cases has turned from an exporter to an importer. For example, China has been reported to import dye raw materials such as vinyl sulfone and H-Acid (l-amino8-hydroxynaphthalene-3,6-disulfonic acid), an important intermediate from India, reversing its previous role as an exporter to India, as local production of these chemicals declined by 50-60% (Times, 2018). As a consequence, prices in India increased by about 30%.

2.8 Changes in approval practice for new chemical plants

Several managers of chemical factories (both foreign and domestic) have mentioned longer approval times for new chemical plants as the local authorities are more careful in scrutinizing such plants. In one example, the stated approval time changed from 6 months to 18 months.

2.9 Impact on foreign competitors

While the tightened environmental regulation in China may have a negative effect on companies sourcing chemicals from China, it also has some benefits for foreign firms in competition with Chinese chemical producers. For example, several Japanese chemical companies benefit from reduced competition from China as a consequence of tightened environmental regulation. Showa Denko expects its operating profit to jump 80% on the year in fiscal 2018 as they profit from price rises for graphite electrodes, demand for which has been driven by China switching to cleaner steel production. Similarly, Japanese PVC producers such as Tosoh and Asahi benefit from China ́s crackdown on coal-based PVC (Nitta, Suzuki, 2018). Indian producers of dye intermediates also profit from the reduced Chinese capacity, which has allowed them to substantially increase prices (Moneycontrol, 2016).

2.10 Changes in Industry structure

The tightening of environmental regulation frequently results in some consolidation within chemical segments as small plants are more likely to be closed down and tend to have less investment capital required to upgrade production processes or to move to chemical parks.

For example, for sulfuric acid, the output of the top 10 Chinese producers rose to 37.5% of the total production in 2017 from 35.6% in 2016 (China Chemical Reporter, 2018d), though the tightened environmental regulation may not be the only reason for this shift of market share.

In a market survey conducted by consulting company Management Consulting – Chemicals, 10 producers of specialty toluene derivatives were examined. It was found that of 10 producers active in 2016, only 4 (40%) were still producing in June 2018. Even these companies reported some short-term production stops in the past. Interestingly, none of these four companies has immediate plans to increase production capacity as they are all located in relatively low-level chemical production zones and thus fear they may be affected by a further tightening of regulation (Management Consulting, 2018).

2.11 Changes in Mindset

The focus on environmental protection has also already led to a partial change in mindset among local government and particularly those responsible for supervising chemical plants. There are reports of scared government officials indiscriminately closing down chemical production in individual locations after a single company has violated environmental regulation. On the other hand, when the author in February 2018 attended a showcase presentation of the Changzhou National High-Tech District, he was surprised to hear that the presentation boasted of shutting down 35 chemical companies. It is certainly a sign of the changing attitude towards environmental pollution that such a statement is now used to high- light the qualities of this industrial zone, rather than to show its restrictions.

2.12 Opportunities for Western companies

Some Western chemical companies may benefit from the tightened environmental regulation. This applies to multinational players producing chemicals overseas that compete with chemicals produced in China, which may become more expensive or suffer from capacity reductions. Even when producing within China, Western companies may benefit from tighter regulation as due to their global processes, their environmental standards are typically already higher than those of local players, resulting in fewer interruptions and cost increases.

In markets targeted both by Western and by Chinese chemical producers, Western players may also benefit from a decrease in competition from Chinese competitors as these may be affected by cost in- creases, capacity reductions and production stops. Another opportunity for dedicated companies is to sell high-value production know-how and pollution control equipment to chemical plants required to upgrade their processes.

Finally, relocation will often require investment in new equipment rather than the reusal of existing equipment. Due to the increased standards, it is more likely that foreign engineering companies get a share of this business.

3 Impact on China ́s chemical industry: Individual companies

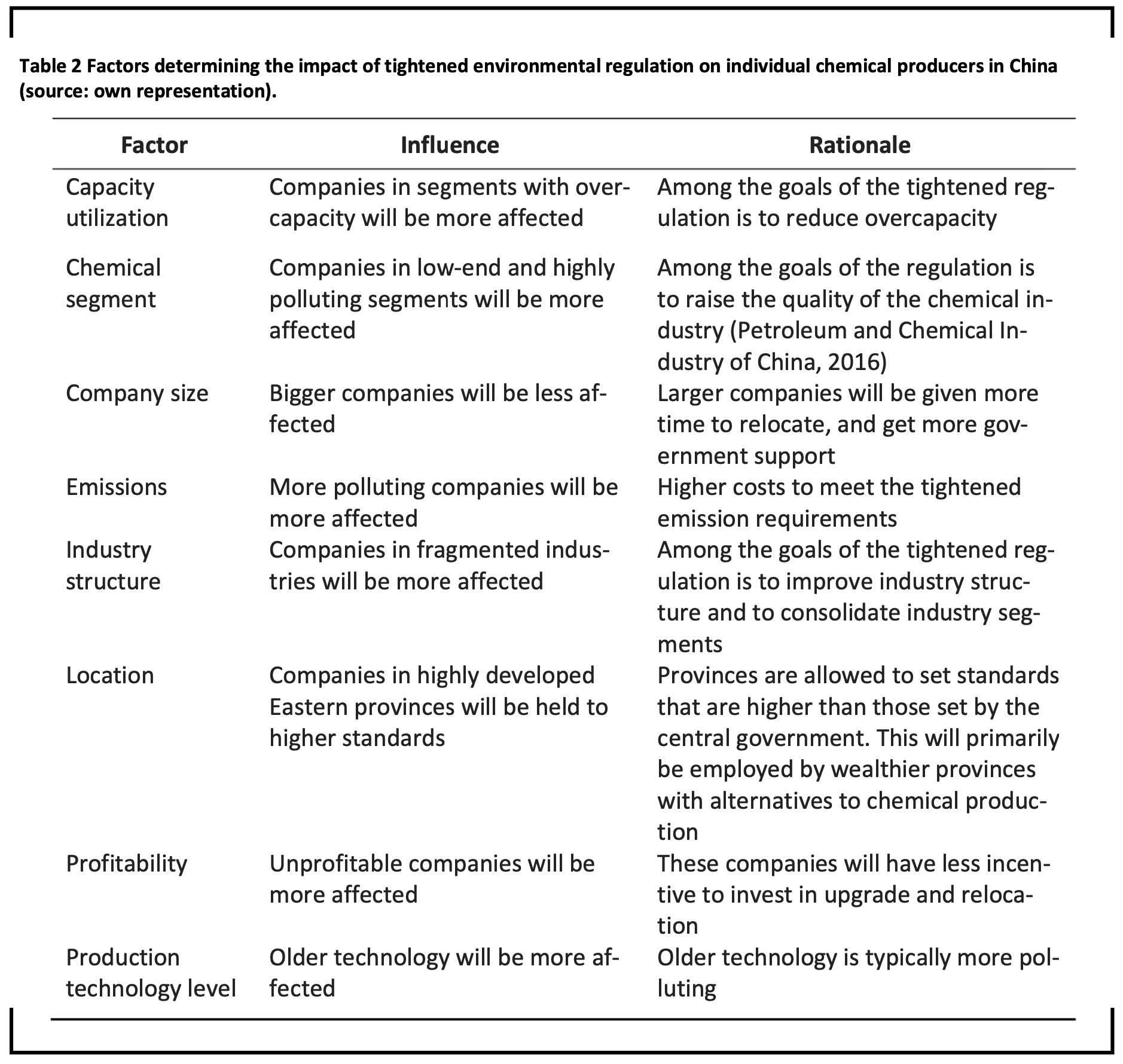

Not all chemical producers in China will be affected by the tightened regulation to the same extent. The table below gives an indication of which parameters determine the impact of the regulation on individual companies.

4 Government objectives

One obvious objective of the tightening of environmental regulation is to improve environmental protection. Closely related is the target of ensuring safe chemical production.

However, several government documents such as the one issued by Fujian province on relocation of chemical companies also hint at an additional objective, the improvement of the industry structure (Fujian Province, 2018): “For those industries with weak market competitiveness and small scale, where there are potential safety hazards in the production and transportation process and do not conform to the direction of industrial development, they should close down and relocate, and do not implement relocation in other places; and those with serious safety risks should be closed as soon as possible. For industries with excess capacity, equal or reduced replacements must be implemented, and no opportunity should be taken to expand production capacity.”

In personal communications with the author, a number of Chinese industry participants stated that indeed the closing down of small and uncompetitive chemical companies and the resulting improvement of margins and reduction of overcapacity are indeed a major objective of the tightened government regulation. Such measures are implemented in a much more direct way in areas such as steel and coal, e.g., via reducing the number of workdays at coal mines or closing down older and inefficient steel plants (Xu and Daly, 2018). In chemicals, such an approach may be less workable due to the large number of different chemical segments and products, which would make it extremely difficult to set suitable targets for the right type and number of chemicals.

However, on the level of individual provinces, some targets are being set with regard to the reduction of the number of chemical companies. Examples for such targets include Jiangsu province and Shandong province (Suratam, 2018). But overall, the central government seems to be confident that increasing the entry barriers and investment requirements for chemical companies (via, e.g., requiring more expensive emission prevention equipment and relocation to chemical parks) will on its own already reduce the number of market participants and reduce capacity, which is generally acknowledged to be excessive for many chemicals.

5 Outlook and Conclusion

There is a general perception among industry participants that the current environmental drive will continue for at least the next few years. Chemical companies cannot expect the current environment of tightened regulations to change. In fact, the relocation plan covers the period to 2025, and it would be a substantial loss of face for the Chinese government to backtrack.

On the other hand, the chemical industry in China is still growing. Revenues of the Chinese chemical and petrochemical industry grew by 12.4% in Jan-Apr 2018 compared to the same period in 2017 (China Chemical Reporter, 2018f). And while obviously not directly comparable with the situation in China, it is worth remembering that as much as REACH was objected to during its introduction in Europe, it is now widely seen as giving Europe ́s chemical industry a competitive advantage (C&EN, 2018).

It is therefore not justified for chemical companies to decrease their focus on China. In fact, industry organizations such as CEFIC predict that China ́s share of the global chemical market will increase further, from 40% in 2016 to 44% in 2030 (CEFIC, 2017).

In fact, the current changes of the Chinese chemical industry from a focus on production volume in- dependent of quality level and environmental consequences to a more balanced model may offer substantial opportunities to those chemical companies that already had to make this switch a few decades earlier. The higher environmental requirements may give Western chemical companies the kind of competitive advantage which – given their decline in their share in China ́s chemical market in the past decade – they were increasingly losing.

References

Akzo Nobel (2018): AkzoNobel Specialty Chemicals breaks ground on €90-million organic peroxide site in China, available at https://www.akzonobel.com/en/for-media/media-releases-and-features/akzonobel-specialty-chemicals-breaks-ground-%E2%82%AC90-million, accessed 15 August 2018.

Beacham, W. (2018): China chemical closures send ripples around the world, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2018/ 01/11/10182191/china-chemical-closures-send-ripples-around-the-world/, accessed Aug 16, 2018.

CEFIC (2017): Facts and Figures 2017, available at http://www.cefic.org/Facts-and-Figures/, accessed 16 August 2018.

China Chemical Reporter (2018a): China issues Emission Standard of Pollutants for Calcium Carbide Industry, China Chemical Reporter 29 (8), p.6.

China Chemical Reporter (2018b): Tianjin to Fully Adopt Water-based Environmental Coatings in 2019, China Chemical Reporter 29 (6) 21 March 2018, p. 5.

China Chemical Reporter (2018c): China to Examine Energy Use in High Energy Consuming Industries, China Chemical Reporter, 29 (8), p.6.

China Chemical Reporter (2018d): Sulfuric Acid: Massive Readjustment to Product Structure, High Input in Environmental Protection, China Chemical Reporter, 29 (5), p.18.

China Chemical Reporter (2017): Harder to Kick off New Hazardous Chemical Projects in Shandong, China Chemical Reporter, 28 (20), p.6.

China Chemical Reporter (2018e): Ups & Downs for China’s Dye Industry While Protecting the Environment, China Chemical Reporter, 29 (7), p.16.

China Chemical Reporter (2018f): China’s Petrochem Industry Posts 12.4% Higher Revenue in Jan- Apr, China Chemical Reporter, 29 (12).

China Chemical Reporter (2018f): Analyzing the Whole Petroleum Industry Status and Forecasting the Prospect of 2018, China Chemical Reporter, 29 (18&19), p.10.

Cinn.com (2018):“我国化工园区建设进入提 质增效新阶段 [China’s chemical park construction has entered a new stage of upgrading quality and efficiency], available at http://www.cinn.cn/cyzc/201806/t20180607_193603.html, accessed 13 August 2018.

C&EN (2018): How Europe ́s chemical industry learned to love REACH, available at https://cen. acs.org/business/economy/Europes-chemical-industry-learned-love/96/i29, accessed 16 August 2018.

Dextra International (2018): Market News – New round of environmental compliance inspection of Chinese chemical industry starts; be alert to impact to plan global sourcing, available at http://www.dextrainternational.com/new-round-environmental-compliance-inspection-chinese- chemical-industry-starts-alert-impact-plan-global-sourcing/, accessed 13 August 2018.

Eastmoney.com (2018):年化工园区建设现状与发展趋势分析 [Analysis on the Status Quo and Development Trend of Chemical Industry Park Construction in 2018], available at http://finance.eastmoney.com/news/1372,20180208832313667.html, accessed 13 August 2018

Fujian Province (2018): Implementation Plan for the Relocation and Renovation of Dangerous Chemicals Production Enterprises, Urban Densely Populated Areas.

Han, P. (2018): OUTLOOK ’18: Asia caustic soda uptrend to continue on strong demand, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2018 /01/ 03/10179177/outlook-18-asia-caustic-soda-uptrend-to-continue-on-strong-demand/, accessed Aug 16, 2018.

Hu, A. (2016): The Five-Year Plan: A new tool for energy saving and emissions reduction, China Advances in Climate Change Research, 7, (4), p. 222- 228.

International Rivers (2018): China Commits to Protecting the Yangtze River, available at https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/ about-international-rivers-3679, accessed 13 August 2018.

Liu,M. (2018): Finally out! Shandong released first list of qualified chemical parks, available athttps://www.linkedin.com/pulse/finally-out-shan- dong-released-first-list-qualified-chemical-huang/, accessed 13 August 2018.

Management Consulting – Chemicals (2018): confidential consulting report

Meng, M., Chen, A. (2018): Chinese chemical producers curb output on new round of inspections, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-pollution-chemicals/chinese-chemical-producers-curb-output-on-new-round-of-inspections- idUSKBN1I80UH, accessed Aug 15, 2018.

Ministry of Ecology and Environment (2018): Xi stresses green development, available at http://english.mep.gov.cn/News_service/media_news/ 2017 0 6/t20170601_415128.shtml, accessed 12 August 2018.

Moneycontrol (2018): Bodal Chemicals Q4: China factor favours vertically-integrated dye makers, available at https://www.moneycontrol.com/ news/business/moneycontrol-research /bodal-chemicals-q4-china-factor-favours-vertically-integrated-dye-makers-2578701.html, accessed 17 August 2018.

Nitta, Y, Suzuki, T. (2018): China’s clean air policy jolts materials market as prices surge, available at https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-Trends/ China-s-clean-air-policy-jolts-materials-market-as-prices-surge, accessed 15 August 2018.

Richardson, J. (2018): China to pause before tightening again on pollution, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2018/ 03/01 /10198376/china-to-pause-before-tightening-again-on-pollution/, accessed 15 August 2018.

Suratman, N. (2018): China pushes ahead with new targets to improve country’s environment, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2018/03/29/10207521/china-pushes-ahead-with-new-targets-to-improve-countrys-environment/, accessed 13 August 2018.

South China Morning Post (2017): New environment tax will hit businesses in China hard, say experts, available at https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/2113650/new-environment-tax-will-hit-businesses-china-hard-say, accessed 14 August 2018.

Tang, F. (2018): Can China realise Xi Jinping’s vision for a green measure of sustainable growth? available at https://www.scmp.com/news/china/policies-politics/article/2125481/can-china-realise-xi-jinpings-vision-green-measure, accessed 12 August 2018.

Times (2018): Double whammy: Spike in dye, cotton prices worry textile industry.

Xinhua (2018): China Exclusive: Chemical factories moved from Yangtze River in central China, available at http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-03/09/c_137027968.htm, accessed 15 August 2018.

Xu, M., Daly T. (2018): China to cut more coal, steel output to defend ‘blue skies, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-parliament-steel-coal/china-to-cut-more-coal-steel-output-to-defend-blue-skies-idUSKBN1GH034, accessed 15 August 2018.

Xu, M., Mason, J. (2018): China’s environment watchdog targets waste as pollution battle escalates available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-pollution-waste/china-to-launch-nationwide-inspections-targeting-illegal-dumping-of-waste-idUSKBN1IC06C, accessed 14 August 2018.

Xu, M., Stanway, D. (2018): China to launch broader environmental inspections this month, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/china- pollution/china-to-launch-broader-environmental- inspections-this-month-idUSL3N1TB022, accessed 12 August 2018.

Zhang, F. (2018a): China Shandong refineries/petchems to cut ops before summit for clean air, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/ news/ 2018/05/24/10224523/china-shandong-refineries-petchems-to-cut-ops-before-summit-for-clean-air/, accessed Aug 15, 2018.

Zhang, F. (2018b):China’s Heilongjiang to shut 14 chemical plants, relocate five, available at https://www.icis.com/resources/news/2018/ 04/26/10215591/china-s-heilongjiang-to-shut-14- chemical-plants-relocate-five/, accessed 15 August 2018.