Sustainability in the chemical and pharmaceutical industry – results of a benchmark analysis

Growing awareness of sustainability

The awareness of sustainability as the main issue of companies’ performance has considerably grown over the last years. The reasons for this development are manifold. On the one hand, global megatrends such as climate change, demographic challenge, global growth of population, etc. have led to growing concerns about the future of nature and the survival of people, especially in developing nations. On the other hand, misleading developments in the management of a large a number of globally acting companies have causedmistrust and a discussion regarding the importance of values and ethics as part of good and sustainable corporate governance.

The discussion of sustainability more or less started in 1972 when the Club of Rome published its first report “The Limits of Growth ”which“ explored a number of scenarios and stressed the choices open to society to reconcile sustainable progress within environmental constraints”.

“The international effects of this publication in the fields of politics, economics, and science are best described as a ‘Big Bang’:over night, the Club of Rome had demonstrated the contradiction of unlimited and unrestrained growth in material consumption in a world of clearly finite resources and had brought the issue to the top of the global agenda.” (The Club of Rome, 2010).

As a consequence, the United Nations started to establish a platform for a structured dialogue about the ecological challenges the global society is facing. Among others, in1982 theWorld Commission on Environment and Development (WCED)was founded, leading to the highly recognized report “Our Common Future” in 1987 (better known as Brundtland Report – named after the Chair of the WCED, the former Prime Minister of Norway, Gro Harlem Brundtland). The report marked the beginning of a definition of sustainability as a

“Development that meets the needs of the presentwithout compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations, 1982)

and it highlighted three fundamental pillars of sustainable development:

- environmental protection,

- economic growth and

- social equity.

This so-called “triple bottom line” has become the frame of reference for most all further discussions about sustainability. Especially the sustainability approach of companies often aims at ensuring a balance of their economic, ecological, and social ranges of responsibility.

Sustainability has attracted companies’ growing attention within the last couple of years. And against the background of a public opinion looking increasingly critically at the way companies are doing their business, sustainability has turned out to be a substantial contribution to ensure their so-called “license to operate”.

The current global economic crisis has given further breeding ground to this development.On the one hand, national governments and global regulating authorities (EuropeanUnion, International Monetary Fund) have undertaken strong efforts in order to develop substantial and successful recovery plans. On the other hand, a discussion about how to realign rules and ways of responsible – sustainable – corporate governance has been gaining momentum. Politics and the global public, in general, are asking

- for more transparency of companies’ decisions,

- for a more long term planning horizon and – as a further consequence –

- for a new performance bonus system for executives being linked strictly to a long term business success and

- for ways to ensure their contribution to both a successful national and global economic development as well as a world being economically, ecologically, and socially in balance.

Sustainable corporate governance seems to have become synonymous with good corporate governance which is at least aiming at a recovery of the credibility of the business and their commitment to contribute to global welfare.

The development described above may serve as proof that sustainability or corporate responsibility (CR) is far more than a buzzword. It has become a rather substantial part of companies’ risk or even opportunity management systems, especially as far as reputation, global procurement, health, safety, environment (HSE) as well as talent management are concerned. What has started as being a more or less soft subject for business has meanwhile evolved into a hard success factor whose negligence may lead to substantial reputational damage and accordingly result in high-cost effects. Furthermore, global standards and global non-financial reporting systems have prepared the ground for giving sustainability a frame for higher commitment and accountability. Against that background, there seems to be no doubt that sustainability will remain on the agenda of companies.

Ernst & Young: Sustainability in the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry – A benchmark analysis

Ernst & Young has long-lasting experience in dealing with sustainability as a strategic product offering on a global basis (Ernst & Young, 2010). We are convinced that sustainability will become a substantial part of the corporate governance of a company. Against that background, it is our understanding that

“Sustainability is about creating long-term shareholder value by embracing opportunities andmanaging risks derived from social, environmental, and economic factors. As with any business issues, sustainability risks and opportunities will be different for each individual company.” (Ernst & Young – Definition of Sustainability).

However, the exposure of companies to sustainability rather depends on their product portfolio and their stakeholder environment. The chemical and pharmaceutical industry has quite a long tradition in dealing with sustainability issues. Coming from a claim to protect the environment, sustainability has meanwhile become a question of health and safety standards. And, it now seems to be defecting to a holistic management approach, covering all main management functions as part of the mission statement and good corporate governance.

This is the summarized result of sustainability research in the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry which has been conducted during the last months by the Climate Change and Sustainability Services Team of Ernst&Young in Germany. So far, we have had a look at about 20 Chemical and Pharmaceutical companies in Germany and at about 17 further global players within the sector.

The objectives of our research were

- to get an impression of the leading chemical companies’ intensity of activities and the commitment to sustainability

- to identify specific fields of strengths and weaknesses in the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry as far as sustainability is concerned

- to identify points of improvement

- to get a deeper insight into future developments and expectations.

We compiled a list of criteria and indicators which we considered to be significant for conveying an impression of the commitment and the activities the selected companies are dedicating to sustainability items. The criteria we identified referred to form and content:

- Sustainability Reporting:

- Does the company publish a sustainability report regularly?

- Does the sustainability report refer to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) criteria?

- If not, is CR/Sustainability presented in the annual report or does the company at least publish reports on special CR issues, e. g. environmental reports?

- Is the sustainability report externally verified?

- Corporate Governance and Sustainability Strategy:

- Does the company have a written mission statement (or core values, vision statement etc.) that refers to sustainability/CR?

- Does the company have guidelines or policies that concretize how sustainability issues should be put into practice (e. g. Code of Conduct, CR Policies, Code of Ethics etc.)?

- Does the company have clear CR objectives or targets – and are these quantified and have a clear timeline?

- CR Organization andManagement

- Does the company have a CR team or a person responsible for sustainability issues?

- Are other departments involved in the CR/sustainability processes (e. g. matrix organizations, Cross-company CR teams)?

- Is the top management directly involved in CR/sustainability?

- Environment

- Do the production sites have a certified environmental management system(ISO 14001 or Eco-Management and Audit Scheme – EMAS)?

- Does the company have clear environmental objectives?

- Does the company collect and publish environmental data?

- How active is the company in the areas of resource protection and savings, compared to others?

- How active is the company in the areas of environment and climate protection, compared to others?

- Does the company produce environmentfriendly products?

- Employees

- Does the company commit itself to meeting international social minimum standards (e.g.HumanRightsDeclaration, International Labour Standards (ILO) conventions)?

- Does the company have clear Human Resources (HR) objectives?

- How strong is the company, compared to others, in the areas of:

- Training and Development?

- Health and Safety at the workplace?

- Diversity?

- Work-Life Balance?

- Does the company conduct employee surveys?

- Supply Chain/Procurement

- When choosing its suppliers, does the company consider social and environmental criteria, and does it give information about its concrete requirements?

- Does the company regularly audit its suppliers and monitor the suppliers’ compliance with the company’s requirements?

- Corporate Citizenship

- Is there a guideline about the handling of donations?

- How strong is the company in the area of Corporate Citizenship, compared with others?

- Other Aspects

- Does the Risk Report pay attention to sustainability risks?

- Is the company included in important sustainability indices?

- Does the company cooperate with universities, Non-governmental Organizations, political or social institutions?

- Does the company actively conduct a strong stakeholder dialogue?

- Is the company member of the “Responsible Care” initiative?

- Is the company member in other relevant industry or business initiatives about sustainability issues?

- CR communication: How comprehensive, transparent, consistent, and easily accessible is the information about CR on the corporate website?

Based on the sustainability informationwhich has been made available to the public (Sustainability Report, Annual Report, homepage, and further publications) we developed a sustainability ranking by awarding credits for each criterion and indicator the company actually meets. Perhaps it is worthwhile mentioning that it is not intended to publish the results of the benchmark in the sense of yet another “good company ranking”. Due to a very heterogeneous data basis (both quantitatively and qualitatively), the benchmark is not meant as an objective ranking – but rather as a first assessment and basis for further discussion.

Main Results

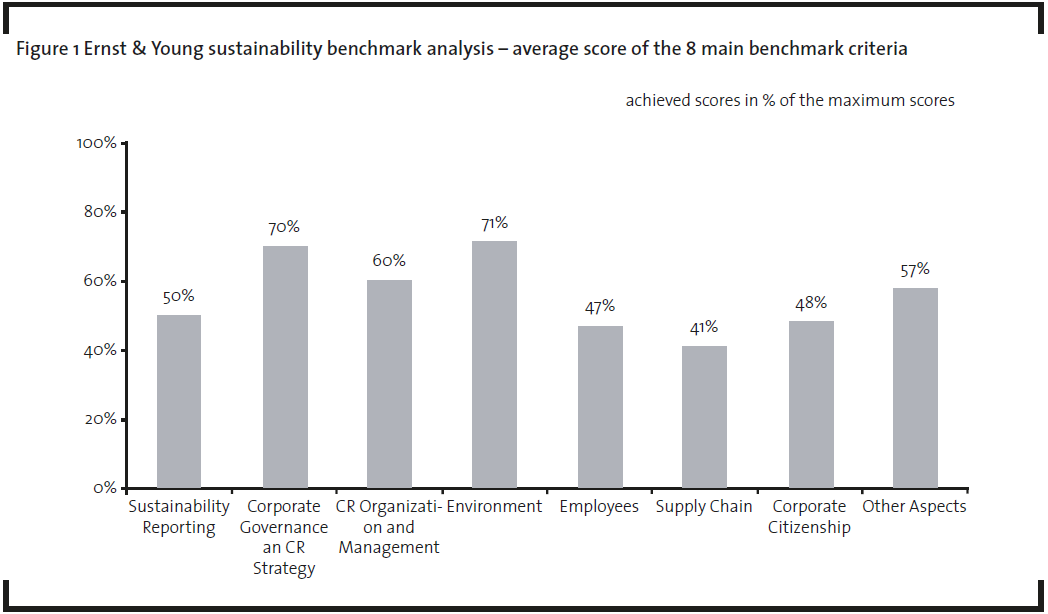

A first overall assessment shows the main strengths of the analyzed companies in the field of environmental activities, whereas main weaknesses have to be stated with regard to supply chain and global procurement. Therefore, this paper will in the following lay a stronger focus upon those two issues whereas further criteria which had been analyzed will be summarized more briefly.

Environment

As already mentioned above, the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry has long experience in the field of sustainability and gave way to a systematic companies’ approach. Several environmental accidents have led to greater concern about the safety operations of the Chemical and Pharmaceutical industries. Especially, the “Seveso disaster” in July 1976 in the region of Milan/Italy resulted in the highest known exposure to Dioxin (TCDD) in residential populations and led to studies and standardized industrial safety regulations. As an example, the EU industrial safety regulations are known as the Seveso II Directive which imposed much harsher industrial regulations.

Since then, governments and multilateral organizations around the world have undertaken active initiatives to protect the environment. Especially in Germany and on a European level a rather extensive environmental legislation process has been implemented during the last decade. Initiatives like the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation, and Restriction of Chemical substances), voluntary programs, carbon or energy taxes, and standards on energy efficiency are just a few examples of respective efforts which have gained impact on companies’ processes, not only in the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry.

Hence, it is not surprising that environmental issues soon became a main focus of the companies’ compliance activities. And, even less surprising, our analysis underlines the relatively high level of activities in the environmental field as well. The 37 inspected companies achieved two-thirds of the total points available on average.

However, new challenges are arising and more and more national governments have just decided to put the protection of the environment on their political agenda. Even latecomer China has started becoming a more active participant in the global climate change talks and other multilateral environmental negotiations and claims to take environmental challenges seriously. President Obama, too, announced higher concern with climate change and plans to become a constructive player in the global discussion on how to prevent climate change.

Those developments were seen as a promising indicator for the UN Climate Summit in Copenhagen in December 2009. The Summit was supposed to lead to a new climate strategy and to replace the Kyoto Protocol from 1997. However, things went differently. The outcome of the conference was more than disappointing as it uncovered the gap especially between the Member States of the European Union on the one hand and countries like China, the United States of America, South Africa, India, Brazil, on the other hand in their commitment in dealing with the Carbon Dioxide matter. The Copenhagen Accord which was drafted by countries such as Brazil, China, India, South Africa, and the United States did not become accepted by the participants of the conference as a legally binding agreement. They just agreed “to take note” of it. Hence, it cannot be considered as an appropriate successor to the Kyoto Protocol whose validation will end in 2012 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2009).

Anyway: Climate Change is and remains the main environmental topic on the global agenda of business and of global and national politics as well. The driving force behind this development is a growing awareness and public discussion of climate change, its consequences to human living, and the demand for providing transparency on the carbon footprint of operations, product life cycles, etc. National governments and global regulatory bodies are of course main forces in giving those activities a mainframe of reference. But also global multi-stakeholder organizations challenge politics and business to provide more transparency and more speed on CO2 management.

Just to name a few prominent examples:

The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) is an independent not-for-profit body and maintains the largest database of primary corporate climate change information in the world. It consequently follows up the goal to disclose CO2 emissions. A growing number of organizations all over the world use this database in order to measure and disclose their greenhouse gas emissions and climate change strategies. And it is the explicit goal of the CDP to “put this information at the heart of financial and policy decision-making.” (Carbon Disclosure Project, 2010).

In order to meet reporting requirements, the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Protocol Initiative, founded in 1998, developed internationally accepted GHG accounting and reporting standards and promotes its use worldwide. The GHG Protocol Initiative says:

“It was designed with the following objectives in mind:

to help companies prepare a GHG inventory that represents a true and fair account of their emissions, through the use of standardized approaches and principles

- to simplify and reduce costs of compiling a GHG inventory

- to provide businesses with information that can be used to build an effective strategy to manage and reduce GHG emissions

- to increase consistency and transparency in GHG accounting and reporting among various companies and GHG programs” (The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Initiative, 2010a)

Today, the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard is the relevant standard for businesses as far as measuring and reporting of the six Greenhouse Gases (carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6)) as listed in the Kyoto Protocol is concerned. Next steps and challenges are still ahead as there are currently high efforts underway to further expanding the scope of GHG-data collection. So far, the instrument covers all direct emissions, i.e. owned or controlled by a company (Scope 1) and all indirect emissions from the use of electricity, steam, heating, and cooling (Scope 2). The next step will be the Scope 3 Standard, which will, for the first time,” allow companies to look comprehensively at the impact of their corporate value chains, including outsourced activities, supplier manufacturing, and the use of the products they sell. Since January 2010 so-called “road testers” of the Product Standard representing 17 countries from every continent and more than 20 industry sectors measure the climate change impact of products.” (The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Initiative, 2010b).

And the next environmental challenge is already under discussion: Water. Its availability is first of all crucial for the survival of human beings and furthermore the main resource for business operations. Due to this outstanding importance there is growing demand that organizations and business operations should approach water similar to their CO2 management. This would among others include mapping the water footprint according to ‘direct, ‘indirect’ or ‘virtual’ water impacts and calculating water risks. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) launched a Global Water Tool at World Water Week 2007 in Stockholm. It became updated in 2009 for the 5th World Water Forum in Istanbul. According to this tool leading questions to assess exposure to water risk is:

- How many of your sites are in extremely water-scarce areas? Which sites are at the greatest risk?

- How will that look in the future?

- How many of your employees live in countries that lack access to improved water and sanitation?

- How many of your suppliers are in water-scarce areas now? How many will be in 2025? (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2010)

The responsibility for protecting the environment is a far-reaching challenge for businesses and operations. The discussion about main points of activities will go on, as elaborations above might have shown. Especially for the Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industry it is a subject of high concern and conjures up main reputational risk factors. But, of course, it also comprises the chance of becoming a first mover (for example in the field of Water) and moderating this process proactively. Therefore, a strategic and systematic approach to assess and monitor environmental challenges is highly recommended.

Questions companies often ask in this regard are:

- What is the right response to climate change and water shortage for today and the future?

- How do I identify, articulate and weigh the implications and impacts for my organization?

- Am I adequately educating the people in my organization to take action about climate change and water shortage and its implications?

- How important is a climate change strategy to my organization?

- What changes are occurring in different locations where my organization operates?

- What are the implications of inaction?

- What are my competitors and peers doing?

- Does my approach provide a competitive advantage?

- Is my strategy helping my organization innovate?

- How do we keep up with changing risks and opportunities?

- How will the implications of climate change and/or water shortage develop over the next few years?

Those questions help to pave the way to develop a tailor-made environmental company profile including elements such as assessment of risks and opportunities, the definition of goals and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), reporting on progress, assessment of reliable data, management guidelines. They are necessary efforts to develop environmental management systems being transparent and accountable.

Sustainable Supply Chain and Global Procurement

Compared to environmental issues that are already paid a rather high attention by analyzed companies, the awareness of potential sustainability opportunities and risks coming up from supply chain management has not yet been sufficiently developed. However, several studies have shown that sustainable supply chain management is an instrument to protect reputation, reduce risks and costs, and enhance revenue growth (Ernst & Young, 2008a).

Efficiency and sustainability are two sides of the same coin. For example, coming back once again to CO2 means in more detail: When there is carbon, there are costs. Hence, knowing the Carbon Footprint of suppliers and building up a carbon-orientated logistic strategy would directly serve to increase cost-efficiency. And there is a clear perspective on market regulations for limited resources. As such the ETS of the European Union has implemented trading periods for carbon allowances. The next period starting in 2013 already foresees the development to auction off of those allowances so that CO2 will soon turn out to be an additional currency company will proactively start dealing with.

Besides environmental challenges, supply chain, and global procurement also touch varying labour standards worldwide. There is a growing concern of the global public community about how companies are dealing with social standards and obligations such as working conditions, children’s work, or even animal testing. According to the wide range of socially relevant questions, there is also a growing number of legally binding regulations on the one hand and a variety of standards companies may comply with voluntarily on the other. Critical incidents of irresponsible handling of social matters within the supply chain have shown a highly sensitive reaction of consumers and the public in general which have repeatedly led to a high damage of companies’ brand reputation. But, the well-managed sustainable supply chain may also serve to further shaping companies’ profiles and to develop a business advantage compared to competitors.

Supply chain can make or break corporate reputation. Supply chain management and global procurement have always been crucial to companies’ business success. All global companies, chemical and pharmaceutical companies, in particular, are aware of the vital importance of their supplier. Traditionally the choice of supplier has mainly been driven by product quality, price, timely and reliable delivery. But the more the public has demanded that products are socially and environmentally responsible, the more those criteria get translated into global procurement decisions. From the perspective of drivers of sustainability, sustainability supply chain management is a kind of litmus test that shows whether a company’s commitment to sustainability is just “greenwashing” or whether it is put into practice. The crucial point in this context is, how a company is treating and developing its global suppliers. Questions here are: Is business at least in line with local standards? Or does the company do even more by transferring fundamental working standards of the western world to partners or sites in the developing world?

When it comes to sustainability, it is necessary to perform a shift in traditional supply chain management. Global procurement and supply chain management have to be expanded on ethical and environmental matters and to be included in established processes. According to that spirit, a sustainable procurement has to include (among others)

- clear standards – socially, ecologically,

- transparent sustainability guidelines

- sensitizing purchasers and suppliers to sustainability expectations

- selection, evaluation, and control of suppliers according to those standards and expectations

- appropriate and clear penalty and

- global coverage.

In achieving these goals the development and implementation of a code of conduct for sustainable supply chain management is highly recommended. Substantial elements of a sustainable supply chain and global procurement management are:

- training of global purchasers and suppliers,

- strengthening the performance of suppliers in NON-OECD countries,

- individualizing suppliers network and training,

- benchmark with procurement settings in competing branches, deciding on compliance with ecological and social standards,

- developing a transparent escalation strategy for non-complying suppliers

- developing transparent evaluation and controlling tools,

- defining clear responsibilities in the supply chain – centralized and decentralized.

Sustainable supply chain management is more than a non-binding add-on to general supply chain management. It has become a crucial point for a company’s risk and reputation management. And, it is foreseeable that this development will gain even more momentum all the more sustainable standards and expectations will get an inherent part of supplier contracts. According to the growing interest in ecological and social product life cycles and management standards, a sustainability strategy will no longer be successful without sustainable global procurement and supply chain management.

Above all: A coherent sustainable Corporate Governance and Management System

In our sustainability analysis, there is a companies’ average of about 68 % of total points in the field of Corporate Governance and the existence of a clearly defined Sustainability Strategy. The interesting message here is that in fact many of the companies we focused on already have sustainability strategies and corporate governance systems in place. However, most of those initiatives have not yet been aligned to a coherent concept. A closer look at the single guidelines, be it the code of conduct, the risk management policy, or any ethical standards, shows that all of them had been developed and implemented with different purposes. Hence, the challenge now lies in revising those policies and putting them in line with one main objective. This might be oriented towards a clearly defined understanding of sustainability as part of good corporate governance. A systematic approach as such would definitely help bring transparency and credibility into the companies’ reputation and help underline and support its “License to Operate”.

Almost 60 % of the points available have been achieved for organizational structure and management systems in the field of sustainability. Best practice examples show that well-organized sustainability management is usually affiliated with a representative of the managing board. This helps to underline that sustainability is of high priority and that it is far away from any kind of arbitrariness. It is a signal which is most important towards external as well as internal stakeholders. With regard to the internal companies’ world very often inconsistency in commitment towards sustainability has to be noticed. On the one hand, there are people highly dedicated to the issue and on the other hand, there are others without a deep understanding of the importance and the potential impact the subject may have on business, reputation, and sales success. However, it is mostly recommended to close this gap and to supply sustainability in form and content with a cross-functional management approach. One main step in this way is to establish a kind of so-called “steering group” with a clear assignment to develop and follow up a tailormade sustainability agenda. In that context, it is of course necessary to cover all main business and working fields, to map local and global dimensions of the business, and hence to include all relevant people into this working process. In any case, one person should be nominated to coordinate and monitor the process and to be the main contact person for all questions which may be raised internally or externally.

Sustainability Reporting

50 % of the total points have been achieved on average in the field of sustainability reporting. There is a clear development of a growing number of sustainability reports being published on a regular basis, either annually or every second year. The reporting standard having been published by the GRI (Global Reporting Initiative, 2010) more and more turns out to be a substantial guideline and orientation frame in terms of the form and content of those reports. The achieved standardization all the more gives liability, accountability, and comparability to the nonfinancial reporting universe. There is no doubt that during the last years non-financial reporting has made a real leap in quality. Feedbacks from financial analysts confirm that information given by sustainability reports is more and more referred to as an additional source to the financial reporting system. Furthermore, a growing number of companies ask for the provision of independent assurance services in relation to their Sustainability Report. Most of those companies are starting with a so-called limited assurance on the HSE – performance data and the HR-related performance data included in the report. In addition, assurance on a number of defined topics and the reporting process is possible. Assurance of the full report is mostly considered to be an option for future years.

There seems to be growing attention of the financial market towards sustainability reporting and socially responsible investment (Ernst & Young, 2008b). Especially, in the process of company evaluation, a growing number of so-called non-mainstream analysts refer to non-financial data provided by those reports. Non-financials may turn out to be one distinctive feature in the evaluation tool. Furthermore, they may also serve as a signal for a long-term strategy of a company and a broader view of potential business risks. Against the background of growing criticism towards a short-term business orientation which the actual financial crisis disclosed to be a misleading perspective, middle- and long-term goals would help round off the picture of a sustainably successful and responsibly acting company.

Employees and HR Management

HR Management is of growing concern and is becoming more and more of a business case. According to the latest studies, talent management is ranked under the ten main business risks of globally acting companies. Furthermore, it becomes evident that the young manager generation has made a substantial shift regarding their criteria for selecting a potential employer (Ernst & Young, 2009). In this context, it is worth mentioning that money and short-term career development can no longer be seen as sufficient to attract high-potentials. It is even more necessary to disclose the attitude of a company on how to live up to expectations regarding the companies’ responsibility for local infrastructure, environment or even more social balance, locally and globally. Employer branding is an inherent part of reputation management and plays a crucial role in attracting talents and therefore ensuring productivity.

Sustainable leadership, open-minded and transparent leadership communication, responsiveness to employees’ concerns, upward feedback, the credibility of leadership proven in a “walk the talk”-culture, and a diversity of cultures and gender are the current success criteria of sustainable HR Management.

Corporate Citizenship

The engagement of a company for its local surrounding or for global burning issues (such as access to medicine, nutrition, etc.) has a long tradition. Companies are free to decide on how their engagement should look like. However, there is a tendency that these engagements to help underline the special competence and profile of a company. This would help to further sharpen reputation and is a question of credibility. Against that background, more and more companies have started identifying projects and subjects they plan to focus on and have begun developing a guideline on how to have this engagement put into practice.

Three different stages of sustainability implementation

The management of single sustainability criteria – as elaborated above – is only one result of the Ernst & Young Sustainability Benchmark Study. It also discloses a broad range of levels of an overall sustainability management approach having been adopted and incorporated in the analyzed companies so far.

There are three more or less well-defined groups:

Group One – the lower level

Companies on the lowest level still have not yet developed their own approach to sustainability. Even if a deeper look at the companies’ process may disclose single initiatives especially in the field of HR Management, environmental activities such as waste management or, last but not least, activities in the field of corporate citizenship, there is no rounded sustainability picture yet.

Against the background of sustainability becoming more and more important to employees, investors, customers, and other stakeholders, it is highly recommended to get an impression of the potential risks and opportunities. A systematic assessment of current sustainability activities and challenges is a necessary first step to get a picture of the specific risks and opportunities the company is facing with regard to sustainability.

Middle-Ranking Group

The second group of companies has a basic understanding of the impact of sustainability on their own business. Coming from a focus on environmental protection, a broader approach that also covers health and safety issues has meanwhile been developed. The so-called HSE or HSEQ (Health, Safety Environment, and Quality) Groups are taking care of the respective items in the management process by developing goals and KPIs, arranging audits and certifications, and developing a reporting system. The HSE(Q) systems mostly cover the main global sites. But, systems often remain partly intransparent and are not incorporated into main management functions, such as Corporate Governance, Global Procurement, Risk Management, Internal Audit, and/or HR. However, for success and credibility, it is crucial to practice sustainability throughout the company, top-down as well as bottom-up.

High-Level Group

Companies represented on the highest level already have a broad understanding of sustainability which is reflected in the code of conduct, management principles, etc. Sustainability is seen as a business case which means that the current and future megatrends mentioned above are a main part of the companies’ innovation cycle and product development. There are only a few shortfalls worth mentioning, which are most likely in the field of talent management and global procurement. Companies in this group are the main benchmark and forefront of further sustainable development in general.

Further prospects of sustainability

The future of sustainability remains to be seen. Its discussion has not yet come to an end – neither in the global community in general nor in politics or companies. There are many interests driving sustainability. Most of them spring from ethical expectations to protect global survival and to enable welfare and social development. With regards to politics, there will be further discussions necessary about how to draw the global bow and to set a regulatory framework helping to ensure the challenges of a sustainable world.

The expectations regarding the role companies may play in this global setting have become more or less clear: Business should account for responsible manufacturing and trading processes: responsible meaning both socially and ecologically. Companies are answering this new ethical attitude by implementing respective structures and processes into their management, by developing goals and reporting efforts and achievements, accordingly. Even if ways of treating sustainability expectations have already led to quite high acceptance and incorporation of sustainability into management thinking, these actions remain to be reactive. However, the more the discussion of sustainability reaches politics, legislation, standard-setting bodies, and the financial world, the more it becomes an element for the creation of business value. This development seems to gain momentum and will make a paradigm shift necessary that will turn sustainability into a basic part of companies’ strategy and in so far into a business case.

Designing sustainability to a business model will be far more than identifying, evaluating, and reporting relevant KPIs of the management process. It will have to go beyond focusing on the reduction of sustainability risks in global manufacturing, on implementing sustainability into buying, selling, and management processes. Sustainable business is a long-term business model. As such it will need to have an impact on market and product development. It will influence innovation processes and will get more management groups of a company and even its controlling bodies involved. Against that background, sustainable management should not only be concentrating on the companies’ adherence to social and ecological standards and reflect them in code of conduct and management behavior. Sustainable management approaches should also turn the question right the way around by asking for the contribution, that sustainability (social and ecological criteria in particular) may give to business development and value creation. If sustainability succeeds in becoming a business driver the reservation and latent criticism towards the gap between business thinking and “greenwashing”- communication might disappear. And more importantly, touching the heart of the business, sustainability will be a criterion for innovation, product development, and the evaluation of business success.

As far as the chemical and pharmaceutical industry is concerned sustainable business strategies will have to meet with both: new challenges in the industrialized world, such as lifestyle diseases or demand for “eco-products”, and the need to help overcome current global challenges, such as hunger, global nutrition, global access to medicine, water shortage and climate change. There will be no doubt that in the future companies will be further commissioned to political goals (e. g. Millennium Development Goals), financial markets expectations, and the acceptance of a further diversified global consumer community. Stakeholders will furthermore represent the virtual expectations of consumers in developing countries who are not able to raise their voices and articulate their claims. The crucial question will be whether companies will be able to turn a moralized global market and political environment into business success.

Sustainability becoming part of business modeling will have to build on at least five more or less well-defined steps:

- awareness and management of sustainability risks,

- identification and management of opportunities deriving form sustainability,

- analysis of future scenarios regarding sustainable regulatory and market developments

- integration into innovation, business life cycle management, and product development and

- changed market appearance, stakeholder management, and reporting.

Ernst & Young as a multidisciplinary solution provider could be the partner with whom to face this new challenge and to accompany companies on their way to a value-creating sustainable business model.

References

Carbon Disclosure Project (2010), available at https://www. cdproject.net/en-US/Pages/HomePage.aspx, accessed 20 April 2010.

Ernst & Young (2010): Corporate responsibility: sustainability in a changing world, available at http://www.ey.com/cr, accessed 20 April 2010.

Ernst & Young (2009): Akademikerstudie 2009.

Ernst & Young (2008a): Green for go. Supply chain sustainability, EYFGM Limited.

Ernst & Young (2008b): Kapitalanlageentscheidungen und Socially Responsible Investment in der Praxis. Global Reporting Initiative (2010), available at http://www.globalreportimh.org/Home, accessed 20 April 2010.

The Club or Rome (2010), available at http://www.clubofrome.org/eng/about/4/, accessed 20 April 2010.

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Initiative (2010a), available at http://www.ghgprotocol.org/standards/corporatestandard, accessed 20 April 2010.

The Greenhouse Gas Protocol Initiative (2010b): Sixty corporations begin measuring Emissions from Products and Supply Chains, available at http://www.ghgprotocol.org/sixty corporations-begin-measuring-emissions-from-products-and-supply-chains, accessed 20 April 2010.

United Nations (1982): Our Common Future-Brundtland Report, 20 March 1982, Chapter 2, p. 54.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2010), available at http://unfccc.int/meetings/cop_15/items/5257.php, accessed 20 April 2010.

World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2010), available at http://www.wbcsd.org/templates/TemplateWBCSD5/layout.asp?ClickMenu=special&type=p&MenuId=MTUxNQ, accessed 20 April 2010.