REACH Effects – Opportunities and Risks for Transfer Pricing

1 Introduction

This article gives a general background to the REACH regulation and reflects on the possible impact of REACH on Transfer Pricing opportunities and risks. REACH stands for Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of CHemicals. Since REACH may provide some opportunities for improving the Transfer Pricing setup of multinational enterprises (MNEs), this article summarises good Transfer Pricing practice with respect to REACH and its potential effects on operations. It furthermore raises interdependencies between REACH and Transfer Pricing topics like cost allocation, base shifting, remuneration of R&D, remuneration of Only Representatives, tax audit strategies, Advance Pricing Agreements, Mutual Agreement Procedures, Transfer Pricing documentation and Transfer Pricing guidelines.

2 Background to REACH

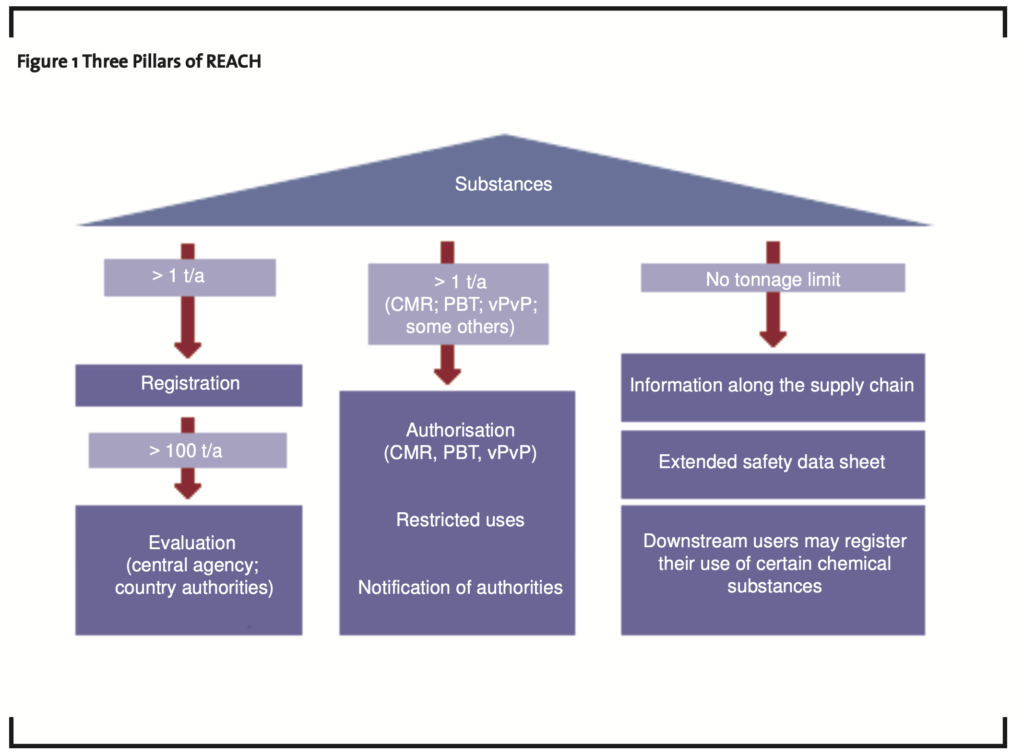

As of June 1st, 2007 the EU 27+3 (27 EU member states plus Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) chemicals legislation changed dramatically. In the upcoming years about 30,000 chemical substances, which are either produced or imported into the EU 27+3, will have to be registered with the newly created European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in Helsinki. The rules of REACH apply to all substances imported or manufactured. The instruments of registration and evaluation form one pillar of REACH, authorisation and restriction of use for substances of high concern form the second pillar and the information flow along the supply chain the third pillar (see figure 1).

- The first pillar “Registration” indicates that all substances in volumes of over one ton per year (1t/a) must be registered by the importers or producers. Also covered in the first pillar are the evaluation tasks to be performed by the authorities under REACH: evaluation of testing proposals and compliance check by the ECHA and substance evaluation by the Member States Competent Authorities. Evaluation under REACH (Title VI of the REACH Regulation) defines the assessment of registration dossiers (examination of testing proposals and compliance check of registrations) and substances. The main objective of the examination of testing proposals is to check that reliable and adequate data are produced and to prevent unnecessary animal testing. The purpose of checking a registration dossier for compliance is to ensure that the legal requirements of REACH are fulfilled and the quality of the submitted dossiers is sufficient, the safety assessment is suitably documented in a Chemical Safety Report (CSR) as required in the REACH regulation, the proposed risk management measures are adequate, and that any explanation to opt out from a joint sub-mission of data has an objective basis. Substance evaluation aims to clarify any grounds for considering that a substance constitutes a risk to human health or the environment. Evaluation may lead to the conclusion that action should be taken under the restriction or authorisation procedures or that risk management actions are to be considered in the framework of other appropriate legislation. Information on the progress of evaluation proceedings is made public.

- The second pillar “Authorisation, Restriction and Notification” applies to all substances of very high concern (SVHC) in quantities of one ton and more per year (1t/a). Title VII of REACH (articles 55-66) covers the criteria for inclusion of substances into the SVHC category. The SVHC category includes carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction (CMR), persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) and very persistent and very bioaccumulative (vPvB) substances. The substances which are subject to authorisation can be found in annex XIV of REACH. This annex currently includes a list of 15 substances but is subject to periodic additions. For these substances, an extended communications regime, including end-users, applies. Restrictions in use as well as notification of articles containing such substances can have far reaching consequences for the manufacturers or importers and thus may impact the global use pattern of such substances.

The third pillar of REACH “Supply Chain Communication” applies to all substances and has no inherent lower tonnage limit. Part of the responsibility of manufacturers or importers for the management of the risks of substances is the communication of information on these substances to other professionals such as downstream users or distributors. In addition, producers or importers of articles must supply information on the safe use of the articles to industrial and professional users, and also to consumers on request. This important responsibility applies throughout the supply chain to enable all parties to meet their responsibility in relation to management of risks arising from the use of such substances. The supplier of a substance or a preparation must provide the recipient of the substance or preparation with a safety data sheet compiled in accordance with Annex II (article 31) and even has the duty to communicate information down the supply chain for substances on their own or in preparations for which a safety data sheet is not required (article 32).

With these instruments REACH regulates the production, the import and the use of che- mical substances in the EU 27+3 market.

The REACH regulation entered into force on June 1st, 2007. The time to implement is quite short. In order to assure a full consideration of the requirements into the standard operating procedures of the industry, the people responsible for the supply chain need to participate fully. Communication with downstream users and ensuring supply of strategically important raw materials – both on the producing/importing end as well as on the following elements of the value chain – play a decisive role in the effects REACH will have on an enterprise. Identifying both, the opportunities and the risks that REACH poses, is crucial. The relevant consequences for the supply chain managers are both the increased risk in the supply chain stability and the opportunity in the increased communication.

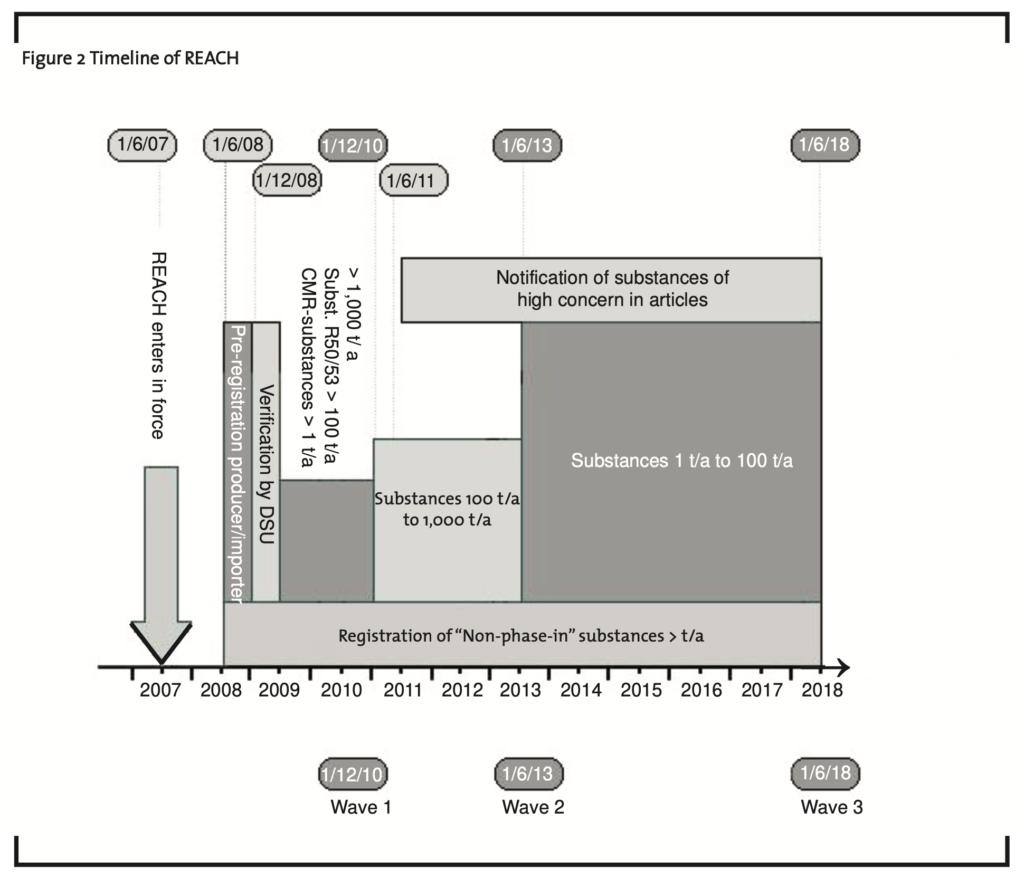

The protection of health and the environment was the foundation of the work on the legislation. However, all the tests, the two-way communication and the inquiries into the use and exposures require a huge amount of work for all participants in the value chain. Over the next eleven years (see figure 2) there are three waves of registrations after the pre-registration in the second half of 2008. First, substances produced or imported in quantities over 1,000 tons/annum (t/a), substances with aquatic impact over 100 t/a and CMR-substances (carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction) over 1 t/a have to be registered by December 1st, 2010. The second registration wave concerning substances between 100 and 1,000 t/a ends on June 1st, 2013. Only in 2018 will all the other substances with volumes over 1 t/a and below 100 t/a need to be registered.

2.1 Complete reversal of the burden of proof

The most direct effect of REACH lies in the reversal of the burden of proof. Now, the industry must document exposure to humans or the environment during normal or reasonably foreseeable conditions of use including disposal of substances in chemical safety assessments and the chemical safety report (CSR). All substances with yearly production or import of over 10 tons must be registered with the CSR. This requires a communication of uses and potential exposure in both directions of the supply chain. The identified uses of a substance need to be included in the safety data sheet (SDS).

Over the coming eleven years the pre-registration, tests and registration of the estimated 30,000 substances are required. Approximately 1,500 of these will be subjected to an intense authorisation procedure due to their CMR properties, because of their assessment result in the classification as persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) or very persistent and very bioaccumulative (vPvB). REACH distinguishes between substances on their own, in preparations and in articles. With the registration the allowed uses as well as the restrictions are available in a central database for the public and the authorities. For the first time it will be possible to build up a detailed picture of where chemicals are used and to show the material flows.

2.2 Extra costs built into the system

REACH will undoubtedly cause extra costs for many players. Currently, the producers and importers are screening their portfolios for the impact of REACH on their costs. The occasion to streamline the portfolio is one factor that has already been identified. No clear indication has yet developed on just how many substances will drop out and not be registered. However, for each individual substance the downstream users will incur a significant cost. The development of alternatives and the qualification of new products with certified uses in the next step of the chain (e.g. as aircraft component, or in a flame retardant function) may cost millions.

Since all steps of the value chain are reviewing their portfolios, the stability of the supply chains is tested to quite an extraordinary extent. Some fear that between 5 % and 20 % of the substances they currently use in their products will not be available or will not be registered for their uses. The likelihood of substance withdrawal is higher for substances in the low tonnage bands and with low margins. Even producers of substances with no obligations to register must be aware of potential downstream exposure issues if they are used in combination with hazardous substances.

REACH requires that consumer products are labelled if substances authorised under REACH are contained in them. Therefore, one possible scenario is the complete elimination of consumer products containing substances with authorisation requirements by large retail chains in some product categories. If this is to occur, many of these substances may be used in much smaller amounts and therefore the fixed costs of the production plants may have to be distributed on a much smaller product base.

2.3 Fundamental differences between producers and downstream users

The regulation differentiates clearly between the role of producers and importers and the role of downstream users (see figure 1). While downstream users are required to implement risk management measures, vendors are now required to supply only to customers where they can be reasonably certain that sufficient risk management measures are taken. For substances with authorisation requirements a rather strict control of this requirement might be introduced.

2.4 The influence of REACH on the supply chain manager

As soon as the downstream user requests the inclusion of his use in the list of allowed uses, the timeframe for inclusion or exclusion in the SDS is one month. If the vendor determines that for health and environmental reasons a certain use cannot be permitted (article 14 REACH regulation), he needs to inform the ECHA as well as the downstream user. Additionally, it has to be documented in the SDS that this particular use is not allowed.

2.5 Opportunities and risks of REACH on the supply chain

With all the preparation needed to comply with REACH, the data and information for substance use in preparations and articles must be gathered. A state-of-the-art response of a company consists of a team of experts from management, regulatory affairs, safety, health and environment, research and development, strategic purchasing, operations, supply chain management and customer facing functions. These multi-disciplinary teams have to identify opportunities and risks along the supply chain. The costs of REACH can be quite significant for specialty chemicals producers. Including these costs in Transfer Pricing considerations may have a significant impact on the bottom line. For this reason, the supply chains in various industries are actively analysed for optimisation potential. On the basis of increased communication – both from customers and suppliers – these efforts may have positive impact on the entire value chain. The early involvement of supply chain experts is highly recommended. Integrating the preparation for REACH into the daily business in a balanced manner requires careful allocation of resources.

The reactions to the entry into force of REACH vary from complete apathy to hyperactivity. Top-management leadership, stringent project management and an integrated team are a few of the critical factors to REACH compliance. Special attention needs to be focused on substances in danger of elimination and on suppliers unable or unwilling to comply with the REACH requirements. The communication in both directions along the supply chain needs to be established early and utilised for a competitive advantage.

3 REACH effects on Transfer Pricing

As mentioned above REACH was not properly taken into consideration by many MNEs and international business in general in the downstream industries since REACH was already drawn up in the years leading up to 2006. Few MNEs prepared themselves properly; others waited for 2008 to react. In the last months not only directly affected MNEs in the chemical industry but also downstream users like the pharmaceutical industry and the plastics industry intensified their efforts to evaluate REACH dependencies and REACH impacts on their operations. Beyond that, REACH effects on Transfer Pricing strategies and operational Transfer Pricing are still seldom assessed in detail.

Since REACH may provide some good opportunities for improving the Transfer Pricing setup of MNEs and international business, this section summarises good Transfer Pricing practice with respect to REACH and its possible effects on operations. This section raises interdependencies between REACH and Transfer Pricing topics like cost allocation, base shifting, remuneration of R&D, remuneration of Only Representatives, tax audit strategies, Advance Pricing Agreements, Mutual Agreement Procedures, Transfer Pricing documentation and Transfer Pricing guidelines.

3.1 Cost allocation

Costs caused by REACH compliance activities of MNEs within the chemical industry can reach significant amounts as mentioned above. They may be allocated to several different entities within an MNE performing functions such as:

- Group headquarter services (e.g. legal ser- vices or patent services)

- Division headquarter services

- Purchasing, supplier management

- Manufacturing/tolling

- Downstream user

- Research & Development (R&D)

- Intellectual Property Rights management

- Distribution/Marketing & Sales

- Syndicate management

How to allocate the REACH costs from a Transfer Pricing perspective is driven by the arm’s length principle, laid down in article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. The arm’s length principle is the international transfer pricing standard that OECD member countries have agreed should be adopted for tax purposes by multi-national enterprise (MNE) groups and tax administrations. Transactions between affiliated companies comply with the arm’s length principle when conditions imposed are comparable to those that are or would be imposed by independent enterprises dealing with comparable transactions in comparable circumstances.

The arm’s length principle treats the members of an MNE group as operating as separate, independent entities. The focus is on the conditions which would have been obtained between independent enterprises in comparable transactions and comparable circumstances. The OECD guidelines provide detailed descriptions of methods that are used to apply the arm’s length principle. These methods fall into three categories:

- Traditional transaction methods

- Transactional profit methods (or profit based methods)

- Other unspecified methods

Traditional transaction methods compare actual prices or other less direct measures, such as gross margins, on third party transactions with the same measures on the controlled party’s transactions. Three methods can be listed:

- Comparable uncontrolled price method (CUP)

- Cost plus method (CPLM)

- Resale price method (RPM)

A transactional profit method, on the other hand, compares the overall net operating profits that arise from intra-group transactions to the net operating profit earned on comparable transactions carried out by independent companies. The transactional profit methods for the purposes of the OECD guidelines are:

- Profit split method

- Transactional net margin method

The transactional profit methods are generally considered to be less precise and reliable than the traditional transaction methods. Nevertheless, they may be applied as a result of practical difficulties in finding suitable information for the application of the traditional transaction methods.

3.1.1 At cost or cost plus mark-up

The question could be raised, as to whether REACH costs should be invoiced with cost plus mark-up (CPLM) or at cost. From an arm’s length perspective, the invoicing of REACH costs at cost and without any mark-up could be justified if an independent third party would be willing to enter into such a transaction. This could apply, for example, where the REACH costs are marginal in comparison to the sales and costs of the operational business. Alternatively, significant cost savings for the provider of the REACH services could justify invoicing at cost. This could be the case if the provider performs the REACH services on his own behalf and on the behalf of associated companies and/or third parties. The savings with respect to the own costs of the provider could be realised due to respective economies of scale resulting from the provision of services for associated companies and/or third parties.

3.1.2 Cost allocation keys

Different allocation keys may be applicable to the cost allocation to entities performing different functions, bearing different risks and providing different assets within the value chain. Possible REACH cost allocation keys could be:

- Distribution between different entities of a MNE on the basis of their:

- Contribution to the Added Value

- Percentage of sales

- Production volumes

- Allocation of all REACH costs with respect to one chemical substance to the:

- Owner/Licensor of Intellectual Property Rights

- Licensee of Intellectual Property Rights

- R&D entity

The REACH principle “No Data – No Market” (REACH regulation article 5) widens the scope of possible cost allocation keys to the above as it considers the whole value chain to be subject to REACH compliance. As a result, REACH costs may be allocated within a MNE to different entities all over the world, not necessarily restricted to the REACH region EU 27+3.

3.1.3 Cost qualification

REACH costs may be qualified by local tax authorities from a tax perspective in different ways:

- They may be seen as deductible expenses.

- They may be qualified as building a capitalised asset in the balance sheet that can be amortised within the asset depreciation range. How long is a respective asset depreciation range with respect to a chemical substance? Does it depend on the product life cycle or is it defined as a lumpsum-range notwithstanding the specific chemical substance in question? Such questions may be governed by local tax law.

- They may be assessed as non-deductible and not building a capitalised asset. Due to article 5 “No Data – No Market”, REACH may be interpreted as a “license to operate” (Temme and de Loose, 2008). This could prevent tax deductions in certain countries. Obviously, only a few countries deny tax deductions. Consequentially, companies will achieve tax benefits due to REACH costs incurred.

If a deduction of expenses or of a capitalisation is possible, tax effects may differ between tax figures in the past and future forecasts of each MNE and its entities. In this respect tax planning effects like tax rate differences and interest effects have to be considered in detail. According to the prospective huge cost volumes in question, the deductibility of REACH costs in different entities within a MNE may have significant tax effects.

3.1.4 Regional REACH cost allocation

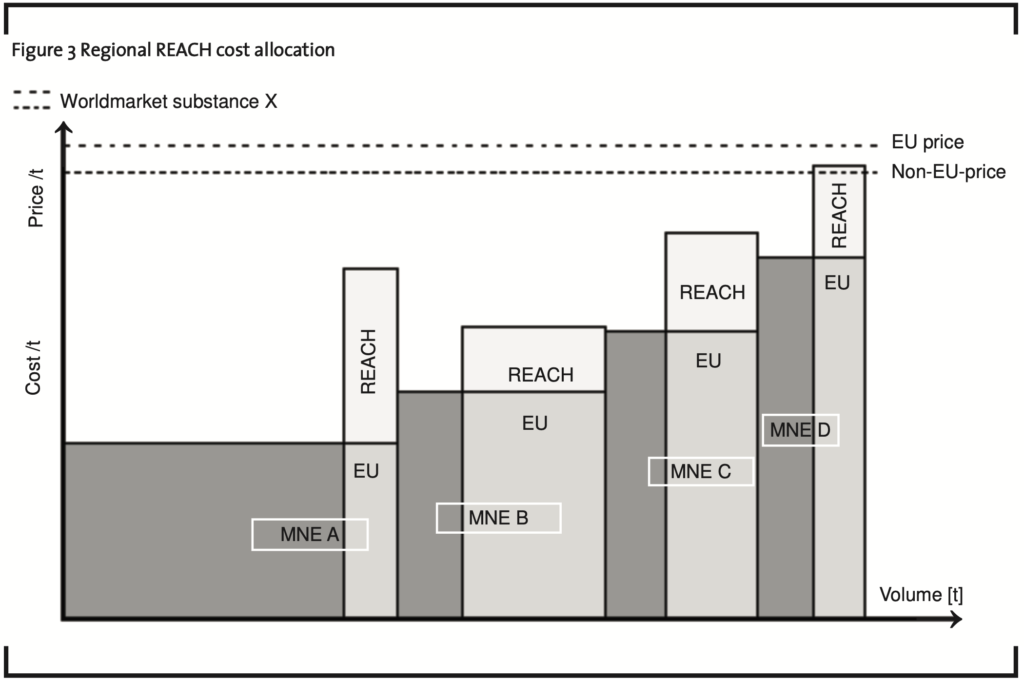

The significant tax effects of REACH costs can be illustrated with the following scenario (See figure 3 and figure 4), covering four MNEs (A, B, C, D). MNE D has the lowest economies of scale2 and therefore realises the lowest gross profits per ton (t) of its production sold to the market. Assuming that the Non-EU 27+3-price is the price before REACH influences the market price for chemical substance X, MNE D is still profitable.

The enforcement of REACH changes the cost structures of all MNEs. The absolute cost increase per substance is assumed to be identical for all MNEs as far as they market/produce substance X in the same tonnage/volume defined in the REACH regulation. But all MNEs have different actual volumes distributed to the EU 27+3-market. Therefore, their cost increase per production ton differs, as shown in Figure 3. The absolute costs per manufacturer are assumed to be in the same tonnage band for manufacturers A, B and C. Manufacturer D however is in a lower tonnage band and therefore has smaller overall costs due to REACH requirements.

As a result, MNE D in our example presented in Figure 3 faces total costs higher than the Non-EU 27+3-price. Therefore, it may be forced to continue activities in the REACH region with losses, trying to reduce cost base in the long run or hoping for an increase of the market price to the EU 27+3-price, as indicated in Figure 3. Assuming that the market price for substance X within the REACH region does not increase to a EU 27+3-price higher than the Non-EU 27+3-price as indicated in Figure 3, MNE D may be forced to stop activities in the REACH region if it does not see any potential for future cost reductions. This would allow MNE D to avoid REACH costs completely.

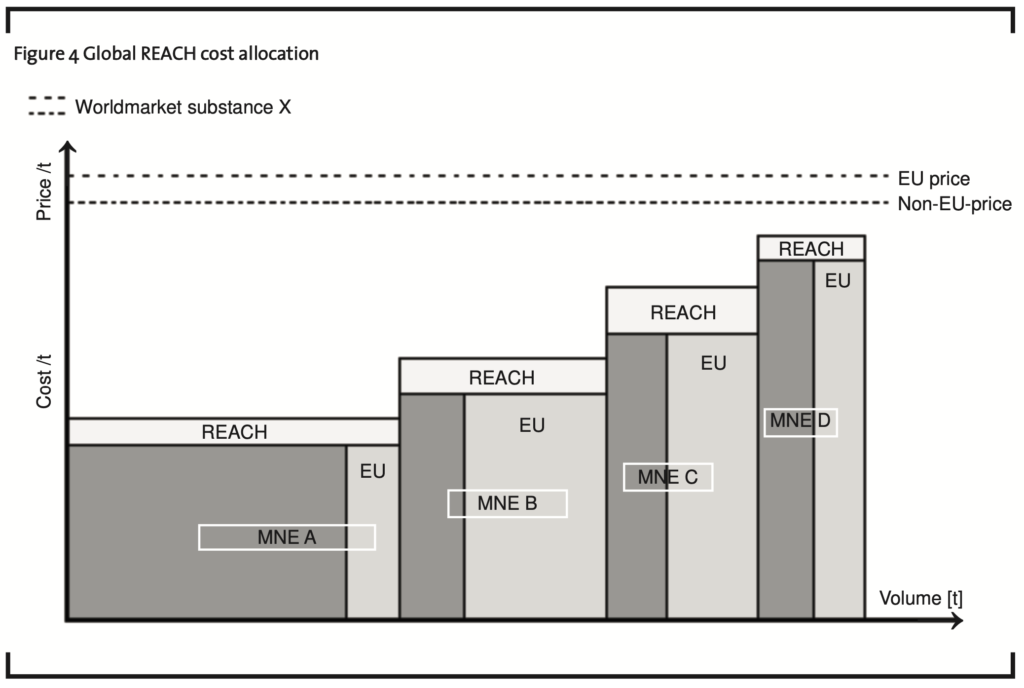

3.1.5 Global REACH cost allocation

Alternatively, the profit-loss situation with respect to each of the MNEs could be described in a different way if REACH costs are seen to be deductible not only within the REACH region, but also in other entities around the world. An economic argument could be that the above mentioned economies of scale of a MNE depend on the production volume worldwide. Consequently, the costs for the production per ton would increase for MNE D as far as necessary to force MNE D to stop producing substance X at all because its new costs per ton are higher than the market price. The global REACH cost allocation model is presented in figure 4.

This model allocates the REACH costs of each MNE with respect to a chemical substance X among all markets/manufacturing entities involved in the business with substance X using the above outlined cost allocation keys.

3.1.6 Statement

From an arm’s length perspective, as considered by the OECD, the allocation of functions performed, including associated risks borne and assets provided, should answer the question if and to what extent regional or global REACH cost allocation is applicable in each individual case. The economic environment, in particular the influences on the competitive situation and achievable economies of scale, may have significant impact on the REACH cost allocation. As REACH costs are very much linked to the REACH region through the “No Data – No Market” principle, at

least a portion of these costs should be allocated to entities within the REACH region. But the more a MNE as a whole is dependent on the continuation and further development of business relations into the REACH region and the more its entities outside the REACH region benefit from activities within the REACH region, the more they should participate by bearing the respective costs incurred. Therefore, global allocation of REACH costs (figure 4) is favourable.

3.2 Opportunities and risks of REACH on Transfer Pricing

Opportunities and risks of REACH on Transfer Pricing cover several topics from Transfer Pricing planning to operational Transfer Pricing. This article presents a selection of Transfer Pricing topics with REACH relevance and describes Transfer Pricing aspects indicating possible solutions.

3.2.1 Impacts on base shifting

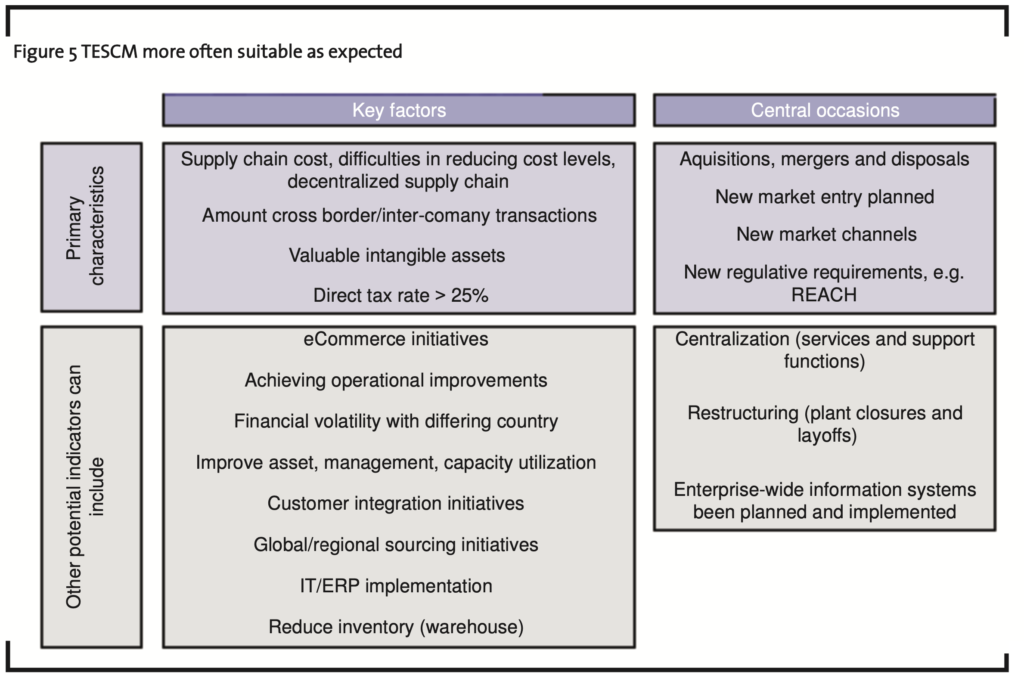

The implementation of REACH and the enforcement of the respective rules may affect competitive environments and encourage MNEs in the chemical industry or downstream users in reassessing their operations on a broad basis, including Tax Efficient Supply Chain Management (TESCM). New regulative requirements like REACH are central occasions and primary characteristics for TESCM. Figure 5 shows a matrix with the columns “key factors” and “central occasions” which may indicate potential for TESCM. The y-axis of Figure 5 groups the entries in both columns as primary characteristics for TESCM or other potential indicators for TESCM.

The in-depth analysis of the implications of REACH from a Transfer Pricing perspective may show that REACH can be an unexpected but very welcome occasion for restructuring projects rescheduled in the past. The advantages for restructuring projects may be caused by the REACH costs having significant impact on the valuation of transfer packages and on the calculation on respective arm’s length exit charges. These effects may change the above mentioned rescheduled restructuring projects, especially if the break-even was only missed slightly.

3.2.2 Remuneration of R&D

As some substances may not be authorised by the ECHA, REACH is expected to accelerate the intensity of R&D activities within the chemical industry to develop substances.3 Downstream users may also develop new manufacturing methodologies to substitute dangerous substances or those no longer authorised. Depending on the extent of changes with respect to R&D within the value chain this may not only increase the R&D costs but also change remuneration models, including royalties for licences or patents. If the R&D activities and REACH compliance are executed by the principal entity, its remuneration with the residual profit will not be significantly affected. In cases of contract R&D or contract REACH compliance services, REACH may exclusively increase the cost basis but not affect the arm’s length mark-up on the respective costs. Questions may be raised with respect to the arm’s length remuneration of Only Representatives.

3.2.3 Remuneration of Only Representatives

According to Article 8 of the REACH regulation, company groups may appoint an EU 27+3 subsidiary as an Only Representative for a group manufacturer of chemical substances located outside EU 27+3.

How should such Only Representatives be remunerated from a Transfer Pricing perspective to meet the generally accepted arm’s length principle?

The ECHA outlines the activities and responsibilities of Only Representatives of manufacturers of chemical substances located outside EU 27+3 in the paper “Guidance on registration” (ECHA, 2008), as follows:

An only representative is fully liable for fulfilling all obligations of importers for the substances he is responsible for as a registrant. These do not only pertain to registration but also all other relevant obligations such as pre-registration, communication in the supply chain, notification of substances of very high concern (SVHC), classification and labelling and any obligations resulting from authorisations or restrictions etc. (see Art. 8(2)).

The only representative registers the imported quantities depending on the contractual arrangements between the “non-Community manufacturer” and the Only Representative.

REACH does not distinguish between direct and indirect imports into the EU and therefore such terms are not used in this guidance. It is essential that there is a clear identification of:

- who in the supply chain of a substance is the manufacturer, formulator or producer of an article;

- who has appointed the Only Representative;

- which imports the Only Representative has responsibility for.

As long as the above conditions are met, it does not matter what are the steps or supply chain outside the EU between the manufacturer, formulator or producer of an article and the importer in the EU.

It should, however, be pointed out that the use of the Only Representative facility creates the need for exact documentation on which imported quantities of the substance are covered by the Only Representative registration and which imported quantities are not. The only representative will need this information to fulfill his obligation under Article 8(2) to keep available and up-to-date information on quantities imported and customers sold to. Moreover, the importer will also need to know whether a concrete quantity of the substance in a preparation is covered by the registration of the Only Representative of the substance manufacturer, as he would otherwise be subject to a registration requirement himself. This documentation will need to be presented to the enforcement authorities upon request.

The registration dossier of the Only Representative should comprise all uses of the importers (now downstream users) covered by the registration. The Only Representative shall keep an up-to-date list of EU customers (importers) within the same supply chain of the “non-Community manufacturer” and the tonnage covered for each of these customers, as well as information on the supply of the latest update of the safety data sheet. For phase-in substances the Only Representative will have to pre-register the substance in order to benefit from the extended registration deadlines and will subsequently become participant of the Substance Information Exchange Forum (SIEF) (see section 3.4 of the Guidance on data sharing).

Subsequently, the first answer to the question, how REACH Only Representatives should be remunerated from a Transfer Pricing point of view, may be: REACH Only Representatives provide authorisation, registration and evaluation services to other group companies. These services are comparable to other routine services provided within the group and therefore should be remunerated accordingly. A usual remuneration method could be the cost plus method, remunerating the cost incurred by the service provider plus a profit mark-up. The definition of such profit mark-ups is usually supported by benchmarking studies, showing profit mark-ups of independent service providers comparable with respect to the kind of services provided considering functions performed, risks assumed and assets employed.

But the activities of an Only Representative are not restricted to services such as monitoring, testing or applying for authorisation, evaluation or registration. Furthermore, Only Representatives are responsible and liable for the fair and true presentation of SDS and all other data necessary for the communication with the ECHA. The corresponding responsibilities may still be classified as routine services. Those may be remunerated with routine profits defined similarly to the ones for other standard services.

With respect to any further obligations against third parties like ECHA or EU 27+3 customers tax authorities may tend to identify the coverage of non-routine risks by Only Representatives. Consequently, tax authorities may assume the remuneration with cost plus a low profit mark-up does not meet the arm’s length principle. In REACH terminology: “REACH Only Representative remuneration may not reach an arm’s length remuneration level”. Therefore, caution is recommendable with a simple roll-out of ordinary intercompany management services agreements not reflecting possible significant differences of the business model implemented with respect to functions performed and risks borne.

Depending on the individual cases and especially the degree or volume of risks covered by the Only Representative a non-routine remuneration or a routine remuneration with a higher profit mark-up may be applicable and feasible. Alternatively, REACH Only Representatives may be protected against liabilities resulting from future claims for damages in an appropriate way. This could be implemented in intercompany REACH Only Representatives agreements. As a consequence, a routine remuneration may be feasible and applicable for the Only Representative. Furthermore, an assessment of possible differences between functions performed and risks assumed compared with other intercompany services agreements is strongly recommended. Such assessments could show the transferability of other remuneration models already applied within the group. Sophisticated assessments and proper documentation of the remuneration models for REACH Only Representatives and their economic background could ease future tax audit defence significantly. Otherwise, adjustments, interest payments and penalties may result in the future.

3.2.4 Assessment of REACH costs in tax audits

For many years local tax authorities have been tangibly strengthening their focus on Transfer Pricing, in particular on management services fees, and therefore MNEs should be prepared for future assessments of large cost pools such as REACH costs. These assessments get more probable in cases of:

- Material tax rate gaps

- Poor Transfer Pricing documentation

- Lack of benchmark studies in place Non-existence of reliable cost allocation agree- ments

- Huge cost pools

- Low profitability and/or loss making periods

3.2.5 APA, MAP, documentation and guidelines

REACH may also be a relevant factor to be considered during Advance Pricing Agreement negotiations with respect to the secondary clauses governing the application of an Advance Pricing Agreement within its validity period. It should be considered at an early stage of tax planning if an Advance Pricing Agreement (including a rollback) approach or a Transfer Pricing documentation and tax audit approach (including possible future mutual agreement procedures) is more feasible for the MNE and its individual Transfer Pricing situation. The quality of such decisions at an early stage depends very much on the deep understanding of strategic Transfer Pricing risk allocation, Transfer Pricing risk assessment and Transfer Pricing risk management. As a consequence, the following should be assessed in detail:

- Transfer Pricing risks involved

- Impacts on Advance Pricing Agreements already in place including possible prolongation negotiations or necessary modifications

- Need for new Advance Pricing Agreement due to REACH impacts

- Impacts on benchmarking strategies for the future

- Necessities for adaptations of cost accounting for REACH purposes

- Opportunities for base shifting and restructuring

- Defendable cost allocation strategies

If REACH leads to significant operational changes in the business models of a MNE or its divisions, this may cause the need for a detailed Transfer Pricing documentation of such extraordinary business transactions to prevent or manage future issues in tax audits. Such documentation should report the relevant considerations and their visible impacts on the Transfer Pricing methodology applied.

Last but not least, Transfer Pricing guidelines in place may need modifications for REACH purposes if the general considerations are not applicable on REACH transactions.

4 Conclusion

The introduction of REACH urges MNEs and international business in general to assess their Transfer Pricing risks from a REACH perspective and simultaneously affords several Transfer Pricing opportunities. In particular, the field of operational Transfer Pricing and other such crucial Transfer Pricing planning topics should be assessed in detail. A REACH Transfer Pricing assessment may cover remuneration of Only Representatives, cost allocation, Transfer Pricing documentation, Transfer Pricing guidelines, remuneration of R&D, base shifting, Advance Pricing Agreements, tax audit strategies and Mutual Agreement Procedures. When dealing with all elements of REACH, one should not only consider the operational and communications aspects but also take a broader view of the need for involvement of tax and accounting specialists.

References

ECHA (2008): Guidance on registration, in: Guidance for the implementation of REACH, May 2008, version 1.3.

EU (2006): REGULATION (EC) No 1907/2006 OF THE EURO-PEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC, in: Official Journal of the European Union, 30 December 2006, pp. 1-849.

KPMG (2005): REACH – further work on impact assessment: A case study approach, A study for UNICE/CEFIC Industry Consortium, DG Enterprise & Industry and DG Environment.

KPMG, TNO, SIRA Consulting (2004): The consequences and administrative burden of REACH for the Dutch Business Community, October 2004.

OECD (2005): Articles of the model convention with respect to taxes on income and on capital, as of 15 July 2005.

Temme, M., de Looze, R. (2008): REACH out to tax you, REACH implementation, in: Specialty Chemicals Magazin, 28 (1), pp. 30-31.